Monthly Summaries

2024 Year End Retrospective

Special Issue 2024

A Review of Media Coverage of Climate Change and Global Warming in 2024

[DOI]

has been another pivotal year when climate change and global warming fought for media attention amid largely tumultuous, competing and intersecting stories around the globe. Climate-related issues, events, and developments garnered coverage through intersecting political, economic, scientific, cultural as well as ecological and meteorological themes.

has been another pivotal year when climate change and global warming fought for media attention amid largely tumultuous, competing and intersecting stories around the globe. Climate-related issues, events, and developments garnered coverage through intersecting political, economic, scientific, cultural as well as ecological and meteorological themes.

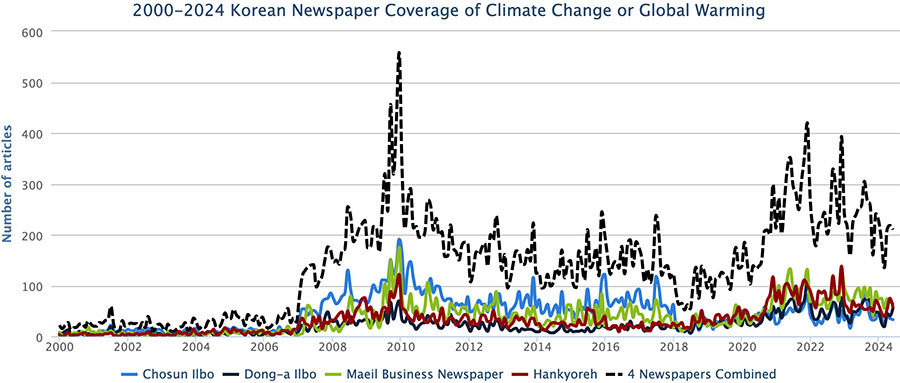

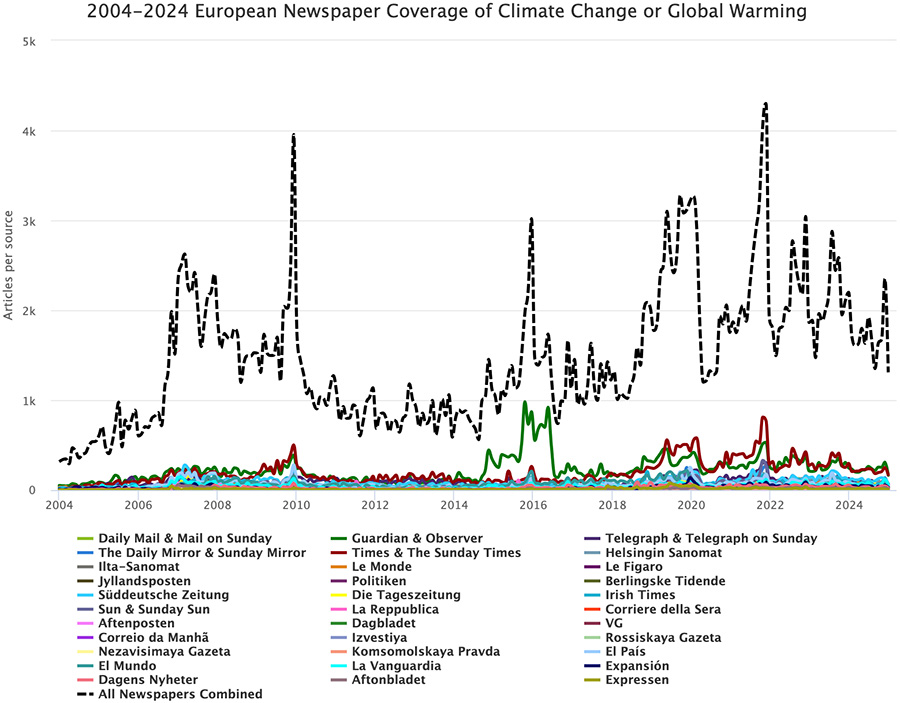

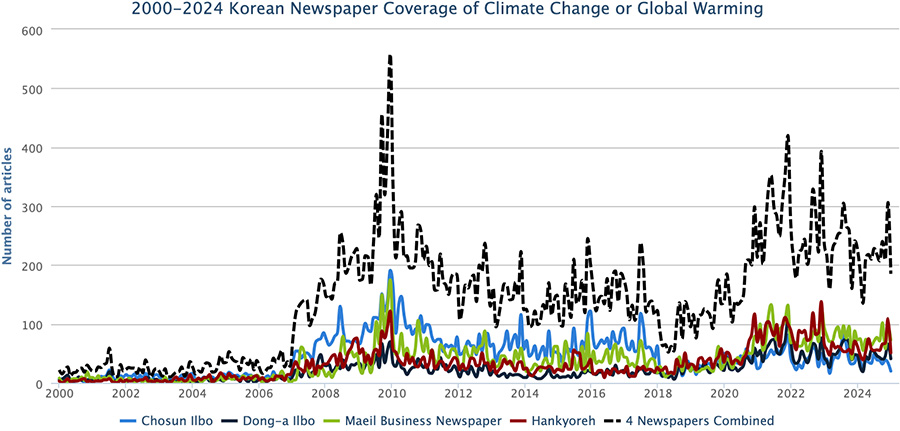

This is our 8th year end report though our monitoring began just over 17 years ago and we have looked at coverage tracking back 25 years to January 2000 in several news outlets. This 2024 retrospective captures the ebbs and flows of media attention paid to climate change around the world while appraising the content covered as we also pull together the year’s monthly summaries from January through December (issues 85-96). Check out our previous year-end reports and monthly explainers here. These assessments uniquely provide guidance on the quantity and quality of news coverage on climate change and global warming across the globe, and across regions and several countries around the world. There is no other media monitoring collaboration like this anywhere else on the globe.

Washington Post president and publisher Philip Graham once posited, “News is a first rough-draft of history”. Our Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) work is therefore effectively a first take on a first rough-draft of history as we monitor and examine media coverage of climate change over this past calendar year. In the pages that follow in this retrospective, our MeCCO team helps to explain the stories – on a month-to-month basis – that shaped a year 2024 of coverage. In the whipping winds and surging storms of breaking news, this retrospective can help us recall, reflect on and learn from what has emerged in news coverage of climate change over the past year as we look ahead to 2025.

MeCCO was established at University of Oxford in 2007. Since 2009, MeCCO has been based at the University of Colorado Boulder in the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES). MeCCO is a multi-university collaboration involving 30 researchers across 15 institutions. In partnership with the University of Colorado Libraries, each month MeCCO provides 25 updated open-source downloadable datasets (as Excel files) that accompany our 50 monthly downloadable figures (as PNG, JPEG, PDF or SVG vector images) capturing coverage across these media and at different scales.

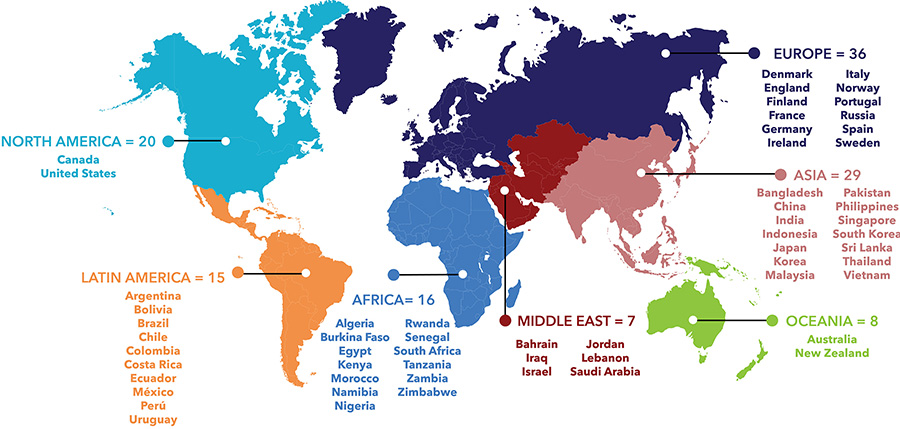

Figure 1. Map of the media sources we monitor for coverage of climate change or global warming across seven different regions around the world.

It is our ambition in MeCCO to provide a solid foundation for analysis of content and quality of coverage over time and place for a variety of users, from fellow researchers to practitioners, government decision-makers, businesses and NGOs as well as interested everyday citizens. Members of our team have published related research in many journals, books and other outlets based on these gathered data as well. Examples in 2024 include contributions to this 2024 Report of the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change that appeared in The Lancet and contributions to this open-access peer-reviewed journal article entitled ‘Vulnerable voices: using topic modeling to analyze newspaper coverage of climate change in 26 non-Annex I countries (2010–2020)’ in Environmental Research Letters.

We continue to pursue this work because methodical tracking of patterns in media representations of climate change or global warming sheds light on what stories are told, what information proliferates, what links are made and – on the flipside – what issues, challenges, opportunities, events and developments remain untold and consequently less understood by those who rely on media to make sense of the world around us. While independent and local/grassroots journalism continue to play important and vital roles, mainstream media outlets to help us understand multi-scale, multi-faceted and complex issues like climate change.

Climate change cuts to the heart of humans’ relationship with the environment, and media provide powerful and important interpretations of climate science and policy, translating issues and information in the public sphere. Media workers and institutions continue to powerfully shape and negotiate meaning as they influence how we all – as citizens of planet Earth – value and make sense of the world in our backyard and around the globe.

The year 2024 featured many activities, events, challenges and issues that drew attention both to as well as from climate change media attention. The movements in 2024 also sparked new phrases, words and terms to describe our distinct and shared realities. For example, Cambridge Dictionary selected ‘manifest’ as the rival Oxford Dictionary selected the phrase ‘brain rot’ while the Macquarie Dictionary from Australia selected the tasteful term ‘enshittification’. So there were many moves from the more hopeful to the more pessimistic takes on prominent developments in this past calendar year.

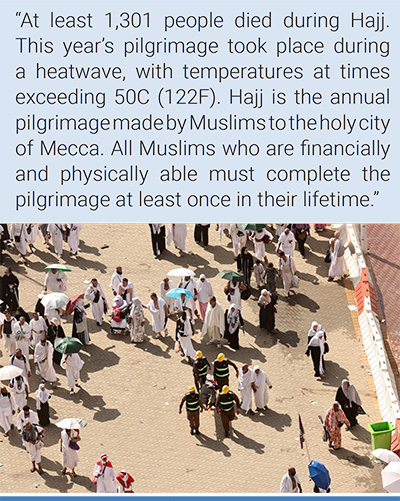

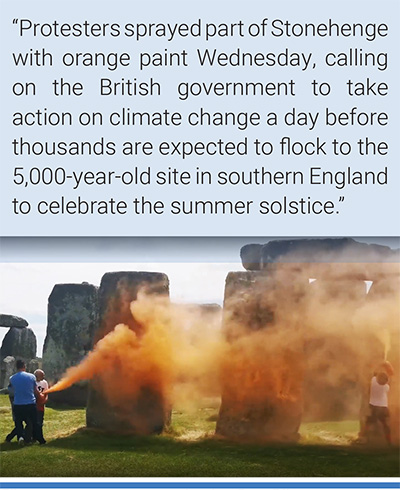

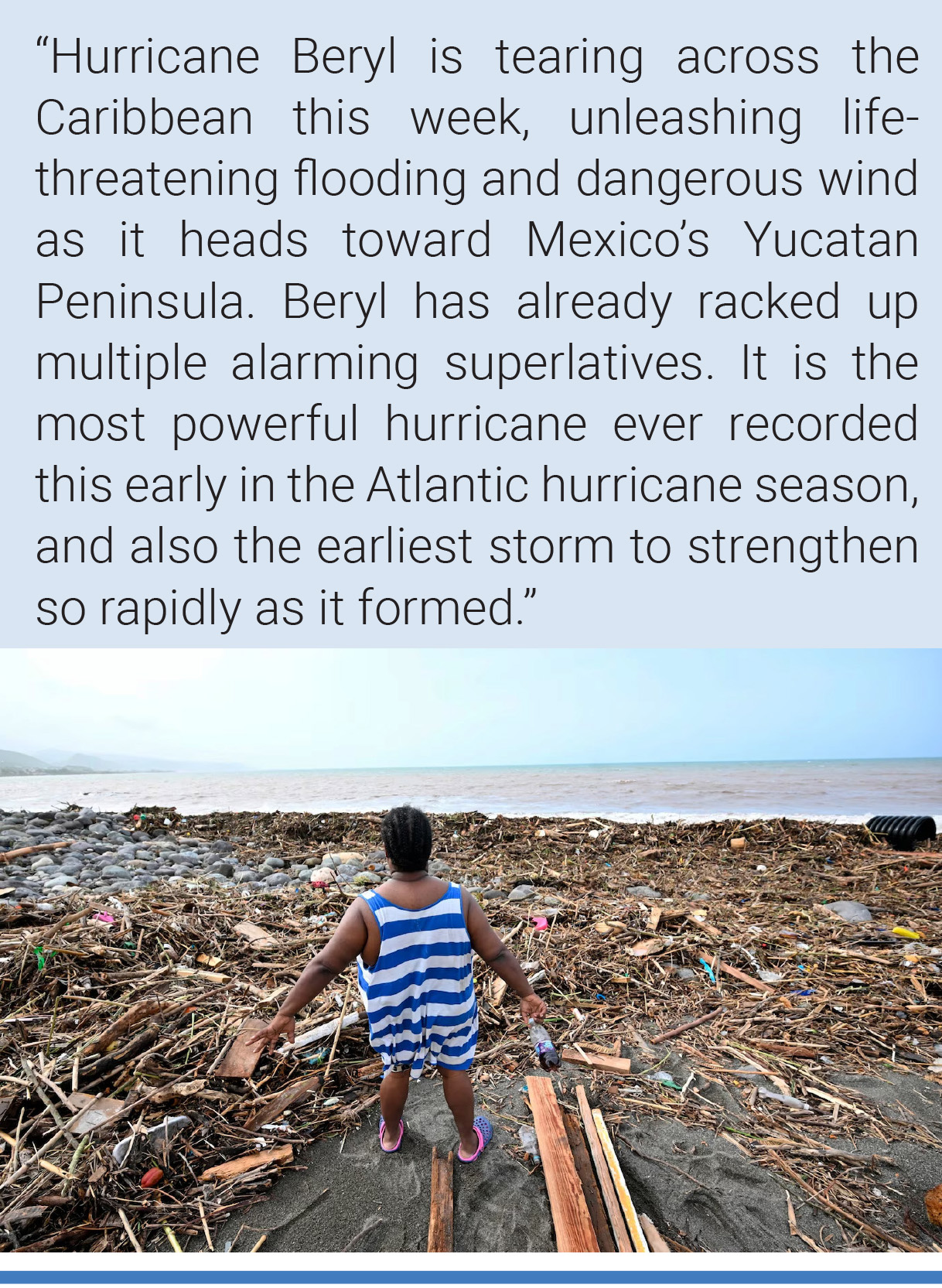

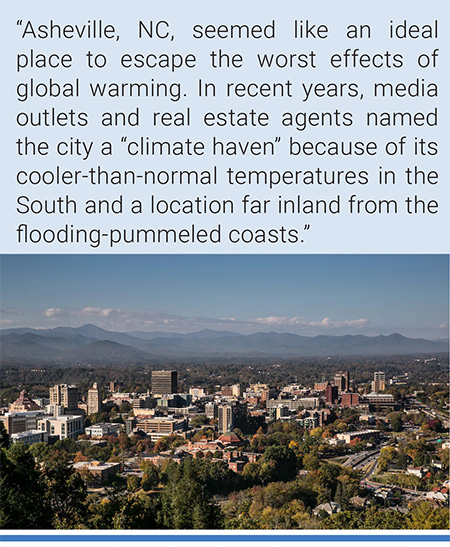

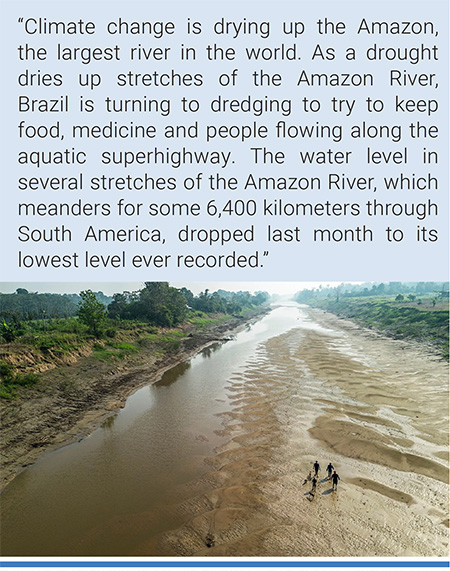

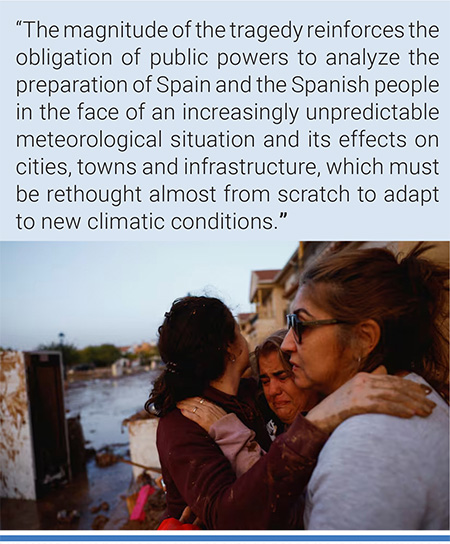

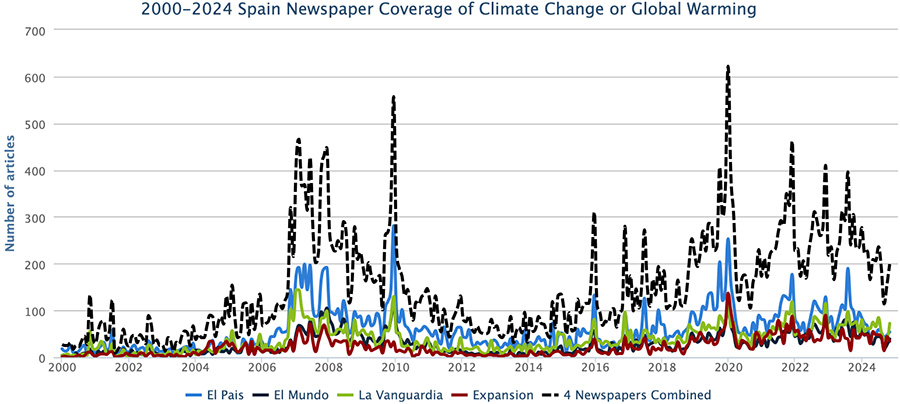

There were many ups and downs as well as twists and turns in both the quantity and content of news coverage about global warming and climate change in 2024. The calendar year started with media reporting like this from The New York Times about a 2% dip in US emissions yet ended with news reports such as this from The Guardian on continued trending in the wrong direction with 2024 marked by the European Union Copernicus Climate Service and the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) as the warmest on record. While media coverage in March like this Washington Post story noted technological improvements in monitoring global methane emissions through the launch of the new NASA/Carbon Mapper satellite, news stories such as this from The Associated Press in November remarked on the links between ongoing methane emissions, ocean warming and an active Atlantic hurricane season (punctuated by Beryl, Helen, Milton and Rafael). And as stories like this one from the BBC covered legal action that began in April a case against British Petroleum linking emissions with negative health effects in Iraq, the year came to a close with a Montana court ruling in favor of young people fighting for rights to a clean environment, with stories making links to global warming like this one from US National Public Radio. Portrayals like this one in Le Mondeabout pilgrims dying in intense Saudi heat during the annual hajj, media accounts like this one in La Vanguardia linking climate change and flooding in Valencia, Spain and coverage like this from The Jerusalem Postnoting how the Arctic has now moved from being a carbon sink (taking CO2 from the atmosphere) to becoming a carbon source (now contributing to climate change) pierced the noise of the everyday of change.

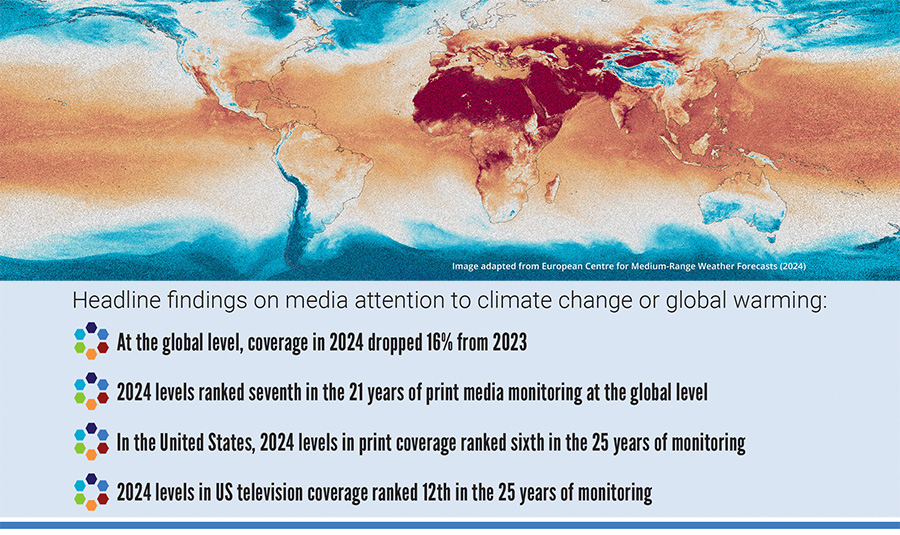

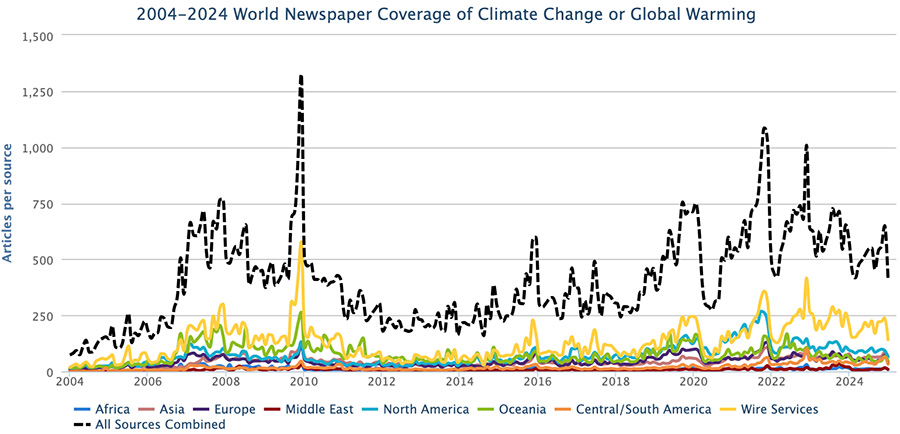

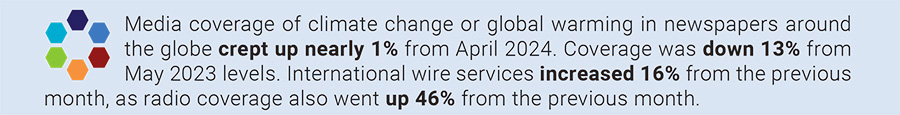

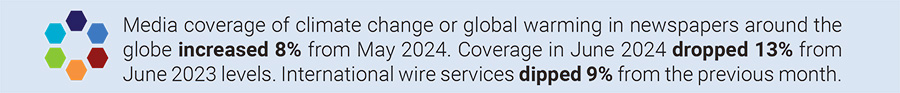

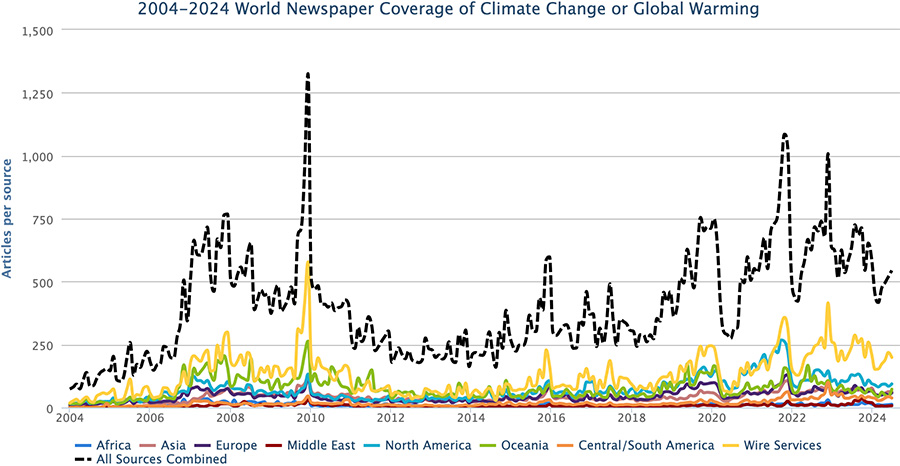

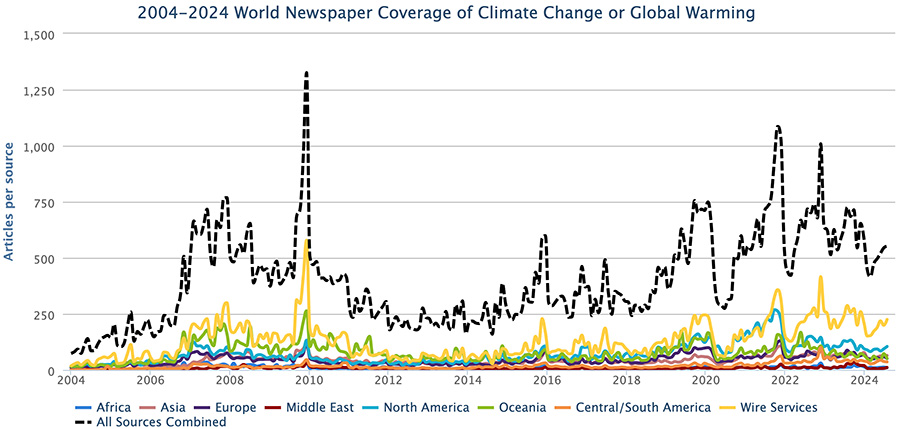

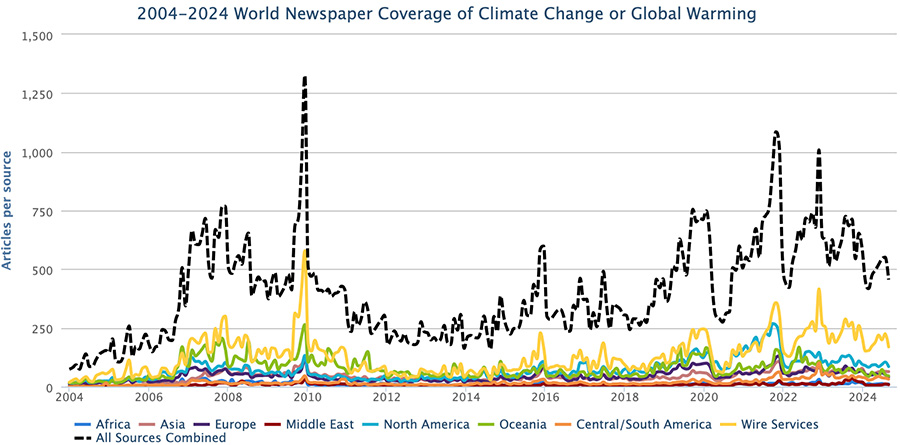

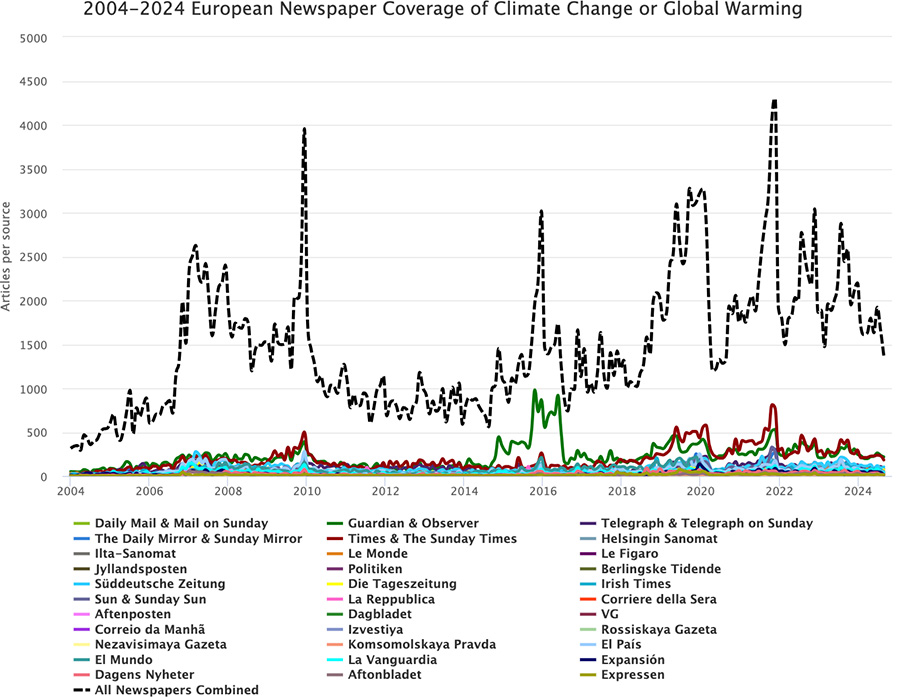

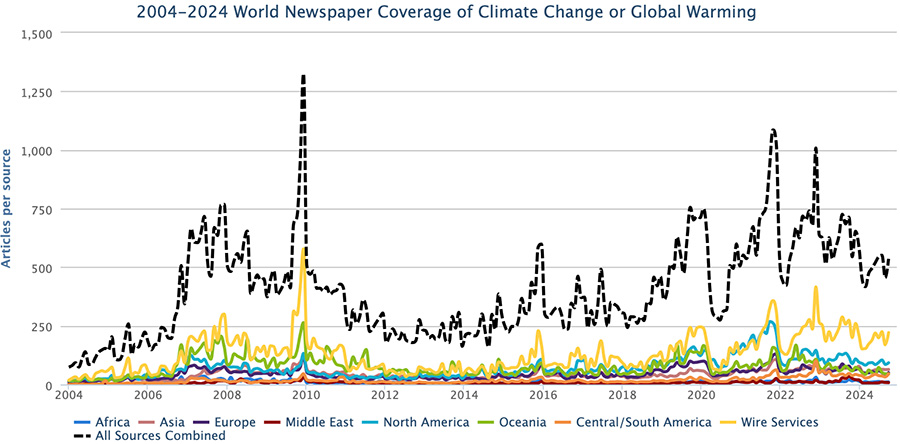

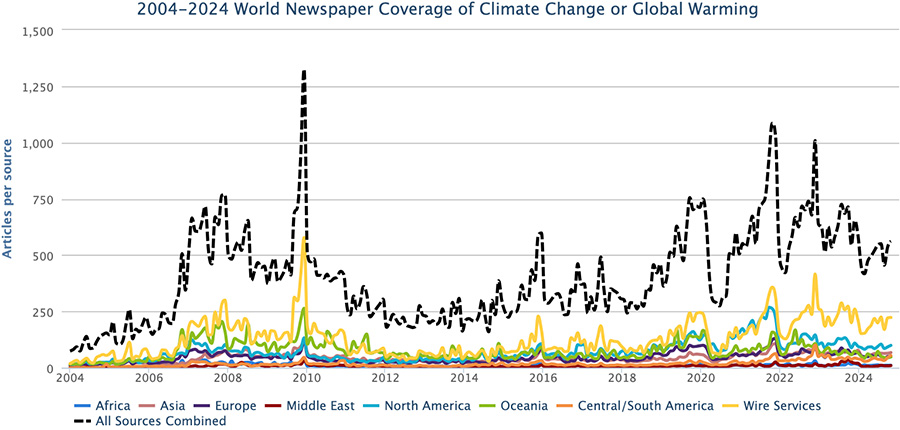

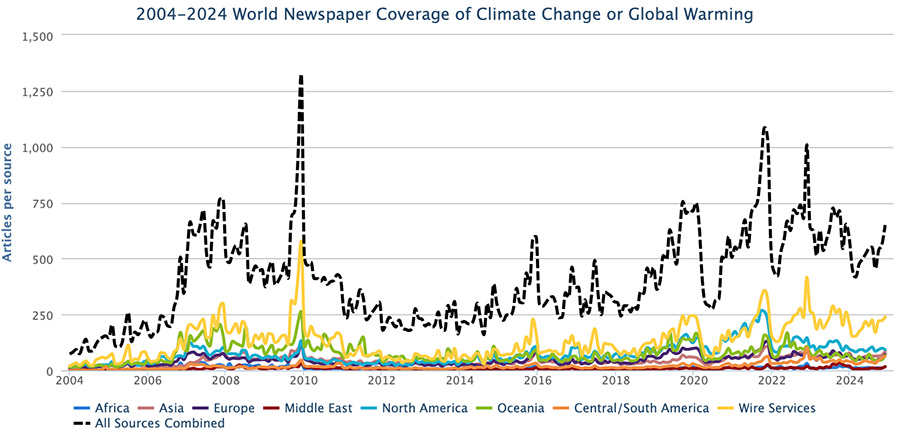

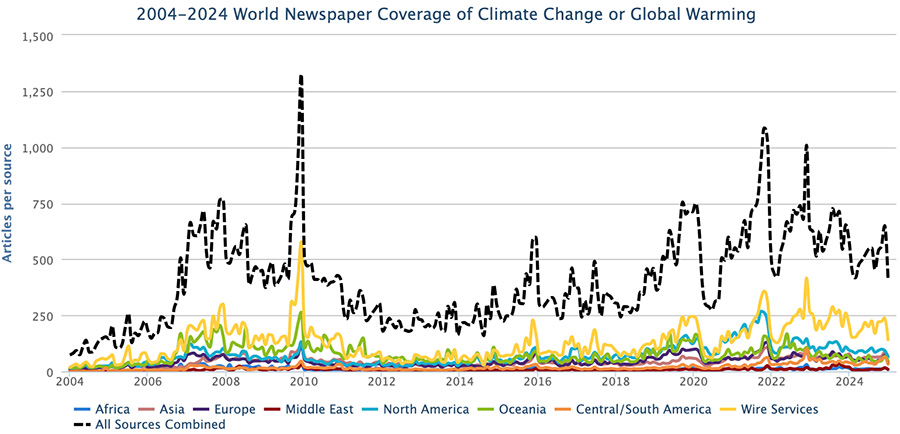

In this past year, what has constituted ‘news’ about climate change or global warming was determined in the context of the warmest year (2024) and warmest decade (2015-2024) in nearly 175 years of temperature records history and the highest atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations since 14 million years ago. Against this backdrop, at the global level the quantity of media coverage of climate change in 2024 dropped 16% from 2023, among the sources that we at the Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) have reliably monitored since we founded the observation network.

Figure 2. Media coverage of climate change or global warming in seven different regions around the world, from January 2020 through December 2024.

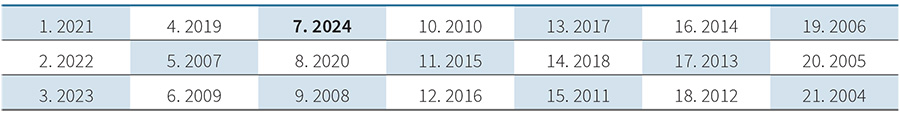

The downturn follows ongoing decreases in the past three years since 2021, which was the year to date with the highest amount of print media coverage globally. 2024 levels ranked seventh in the 21 years of print media monitoring at the global level (see Table 1).

Table 1. Global-level print media coverage of climate change or global warming, ranked by year (1 = highest amount of coverage).

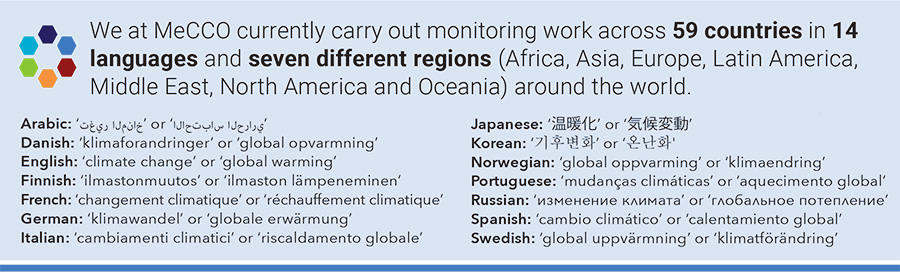

We continue to monitor coverage across 59 countries in 14 languages and seven different regions (Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America, Middle East, North America, and Oceania) around the world.

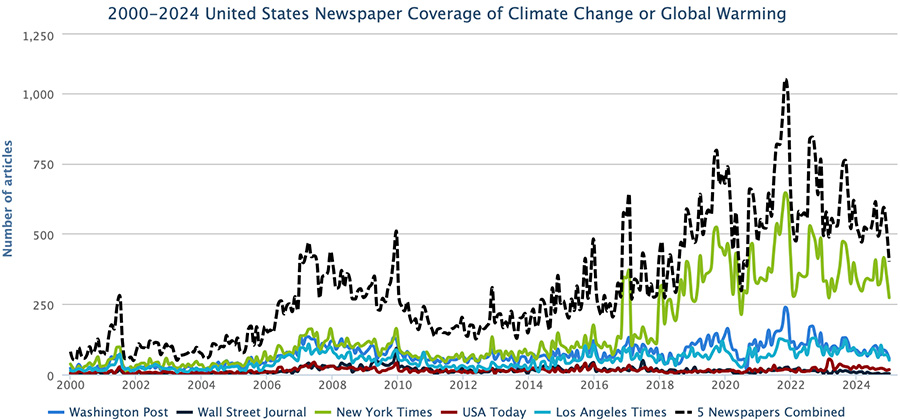

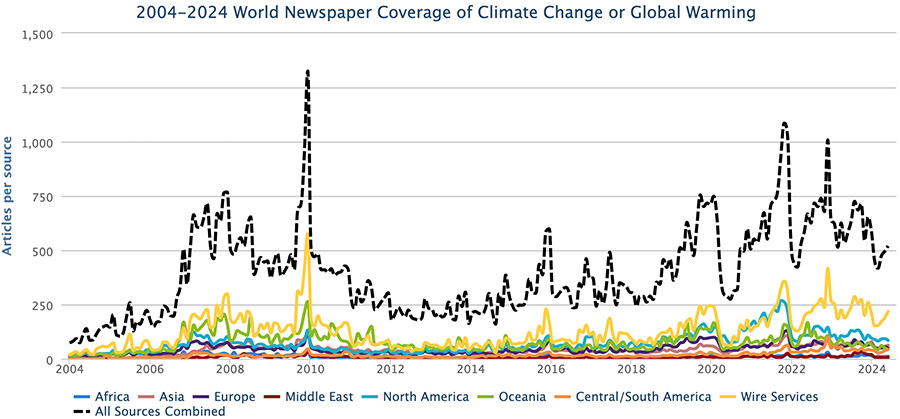

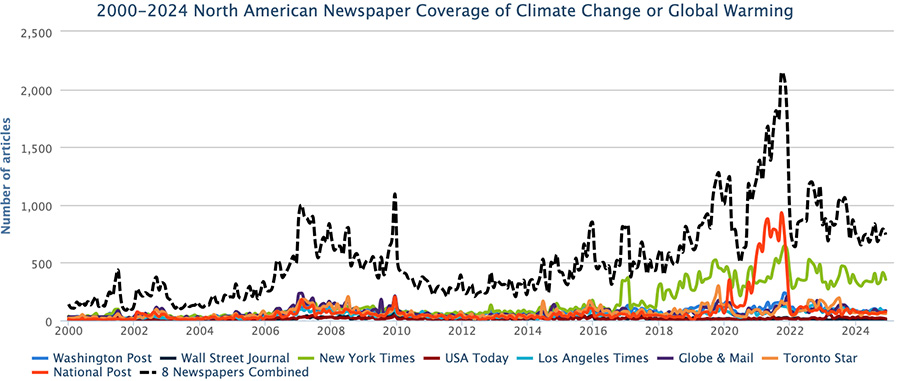

In United States (US) English-language print newspaper coverage since 2000 has seen many increases and decreases (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Media coverage of climate change or global warming in seven different regions around the world, from January 2020 through December 2024.

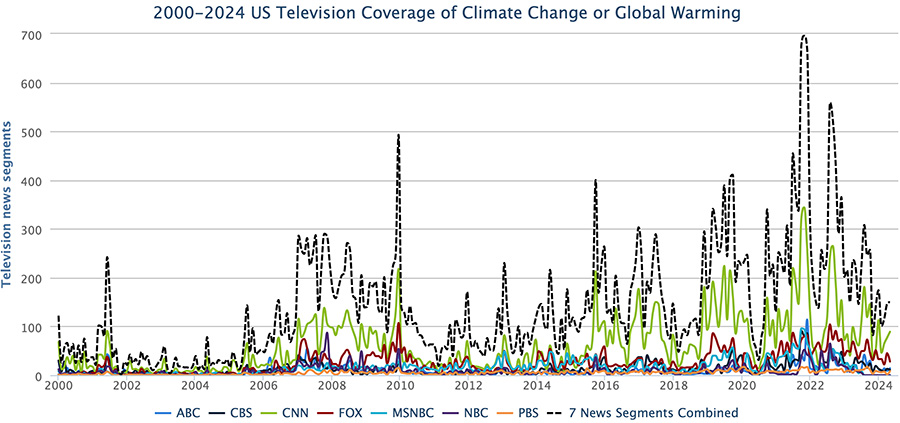

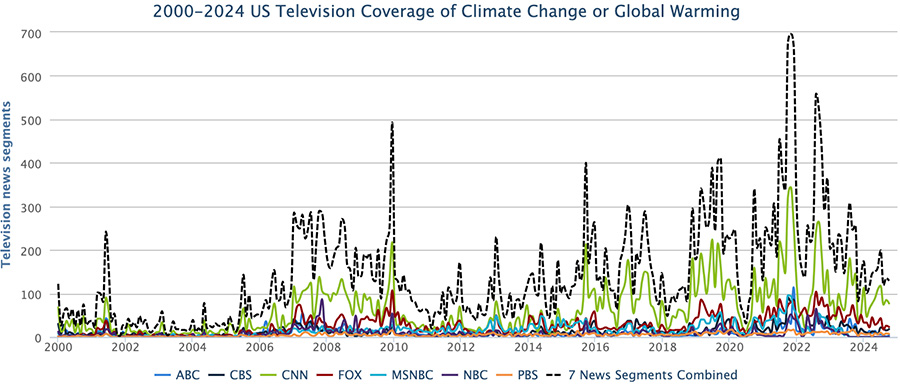

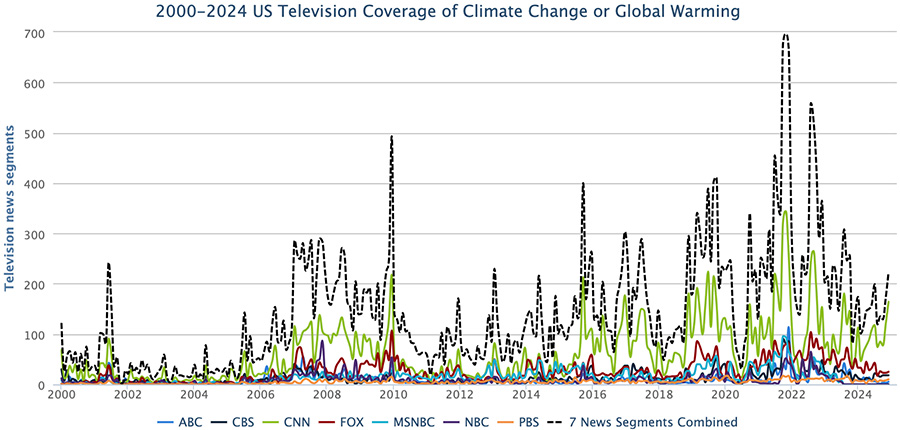

At the US national level, 2024 levels in print coverage ranked sixth (see Table 2) while 2024 levels in television coverage ranked 12th in the 25 years of monitoring (see Table 3).

Table 2 (left). US-level print media coverage of climate change or global warming, ranked by year (1 = highest amount of coverage).

Table 3 (right). US-level television media coverage of climate change or global warming, ranked by year (1 = highest amount of coverage).

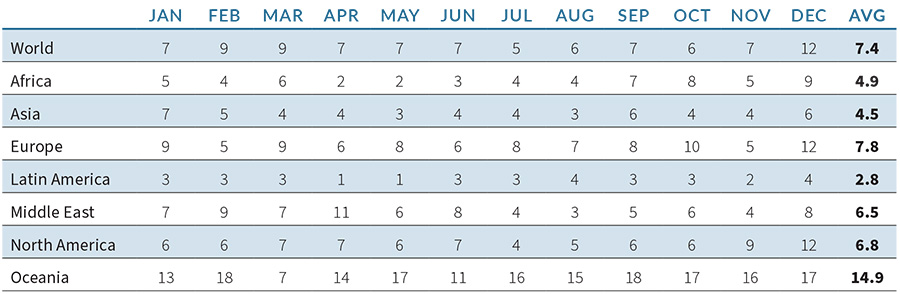

When averaging the 2024 coverage, it can be seen that Latin America is the region that has had the highest coverage in 2024 compared to previous years, while Oceania has been the region with the lowest (see Table 4).

Table 4. Relative rankings of the volume of media coverage of climate change or global warming in seven different regions around the world, from January 2024 through December 2024 compared to previous 21 years.

In this look back at 2024, we invite you to page through each month of explainers that follow as you reflect on how the past year of media coverage of climate change may shape 2025 and beyond.

World's largest iceberg drifting away from Antarctica captured by drone vision in this video. Credit: The Guardian.

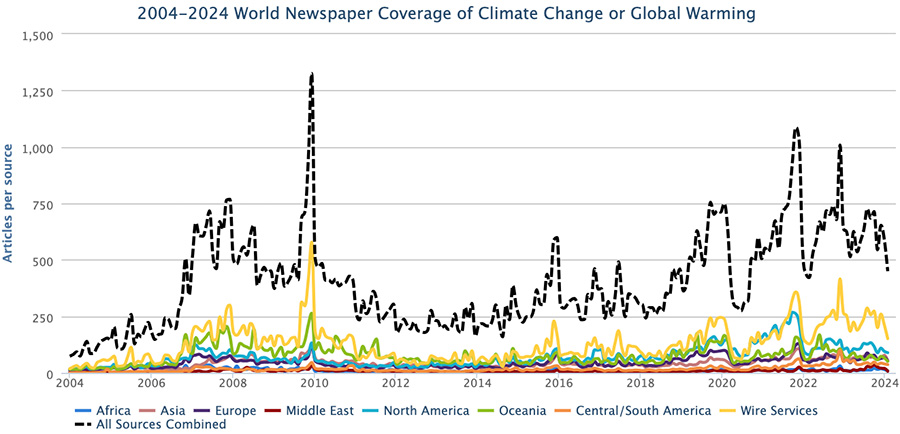

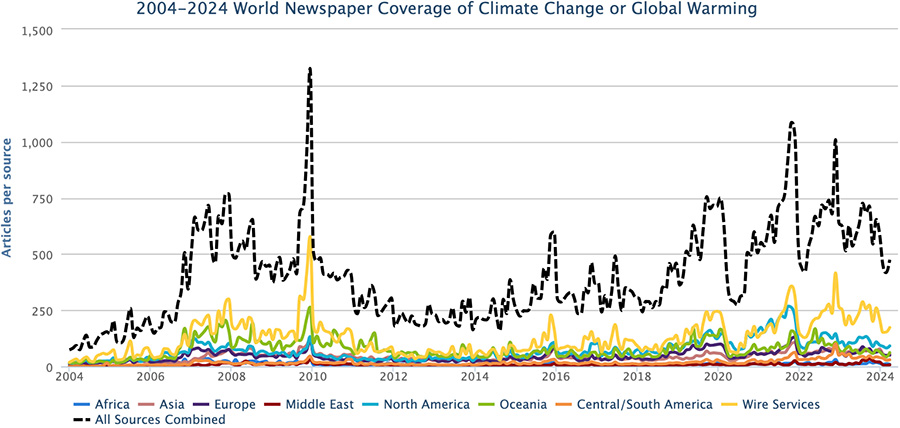

January media coverage of climate change or global warming in newspapers around the globe plummeted 23% from December 2023. Also, coverage in January 2024 dipped 20% from January 2023 levels. Figure 1 shows trends in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – from January 2004 through January 2024.

Figure 1. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in print sources in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through January 2024.

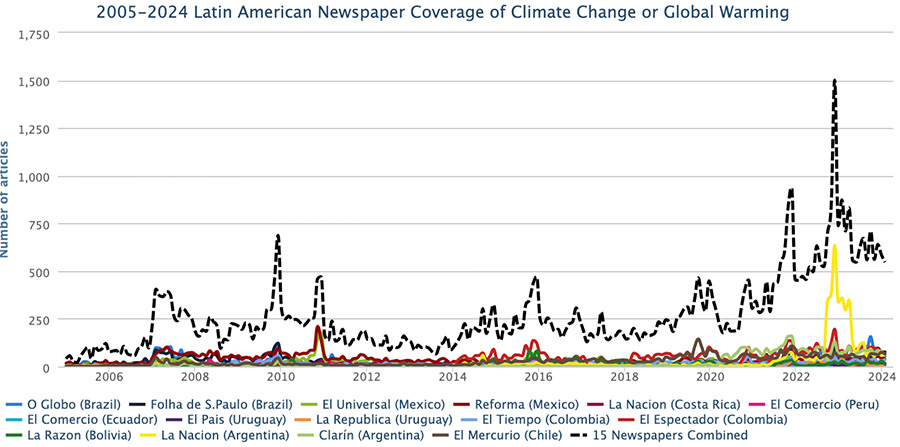

At the regional level, January 2024 coverage decreased in North America (-6%), Latin America (-7%) [see Figure 2], Asia (-14%), the European Union (EU) (-21%), Oceania (-23%), Africa (-38%) and the Middle East (-64%) compared to the previous month of December.

Figure 2. Newspaper coverage of climate change or global warming in Latin American newspapers from January 2004 through January 2024.

Our team at the Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) continues to provide three international and seven ongoing regional assessments of trends in coverage, along with 16 country-level appraisals each month. Visit our website for open-source datasets and downloadable visuals.

Scanning content in January 2024 coverage, many scientific themes continued to emerge in stories during the month. To illustrate, research findings focused on snow and climate change earned media attention early in the new calendar year. For example, Washington Post journalist Maggie Penman reported, “Snow is piling up across much of the United States this week, but new research shows this is the exception rather than the rule: Seasonal snow levels in the Northern Hemisphere have dwindled over the past 40 years due to climate change. Even so, snow responds to a warming planet in different ways. “A warmer atmosphere is also an atmosphere that can hold more water,” said Alex Gottlieb, a graduate student at Dartmouth College and lead author on the new study in the journal Nature. That can increase precipitation, spurring snow, or even extreme storms and blizzards that offset the effect of snowmelt amid warmer temperatures. That has made it harder for scientists to calculate how snowpack has changed over time. But the new findings reveal that areas of the United States and Europe are nearing a tipping point where they could face a disastrous loss of snow for decades to come”.

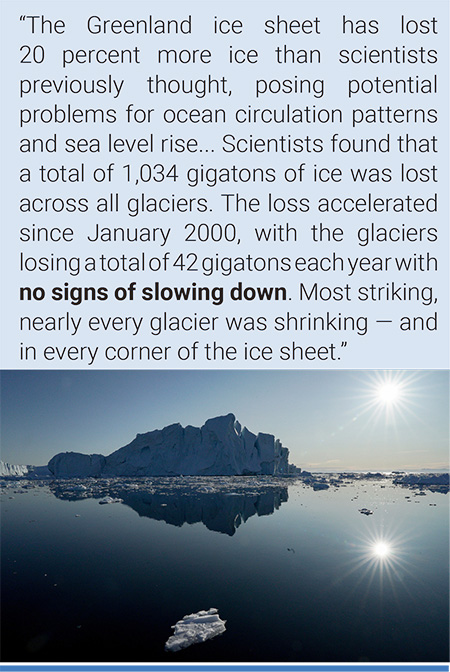

Icebergs that broke off from a glacier in Greenland. Photo: Bonnie Jo Mount/The Washington Post. |

Research examining continued ice loss in Greenland also generated media attention in January. For example, Guardian environment editor Damian Carrington reported, “The Greenland ice cap is losing an average of 30m tonnes of ice an hour due to the climate crisis, a study has revealed, which is 20% more than was previously thought. Some scientists are concerned that this additional source of freshwater pouring into the north Atlantic might mean a collapse of the ocean currents called the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (Amoc) is closer to being triggered, with severe consequences for humanity. Major ice loss from Greenland as a result of global heating has been recorded for decades. The techniques employed to date, such as measuring the height of the ice sheet or its weight via gravity data, are good at determining the losses that end up in the ocean and drive up sea level. However, they cannot account for the retreat of glaciers that already lie mostly below sea level in the narrow fjords around the island. In the study, satellite photos were analysed by scientists to determine the end position of Greenland’s many glaciers every month from 1985 to 2022. This showed large and widespread shortening and in total amounted to a trillion tonnes of lost ice”. Meanwhile, Washington Post journalists Kasha Patel and Chris Mooney wrote, “The Greenland ice sheet has lost 20 percent more ice than scientists previously thought, posing potential problems for ocean circulation patterns and sea level rise, according to a new study. Researchers had previously estimated that the Greenland ice sheet lost about 5,000 gigatons of ice in recent decades, enough to cover Texas in a sheet 26 feet high. The new estimate adds 1,000 gigatons to that period, the equivalent of piling about five more feet of ice on top of that fictitious Texas-sized sheet. The additional loss comes from an area previously unaccounted for in estimates: ice lost at a glacier’s edges, where it meets the water. Before this study, estimates primarily considered mass changes in the interior of the ice sheet, which are driven by melting on the surface and glaciers thinning from their base on the ice sheet. The study, released Wednesday in Nature, provides improved measurements of ice loss and meltwater discharge in the ocean, which can advance sea level and ocean models. Loss from the edges of glaciers won’t directly affect sea level rise because they usually sit within deep fjords below sea level, but the freshwater melt could affect ocean circulation patterns in the Atlantic Ocean…The researchers tracked changes in 207 glaciers in Greenland (constituting 90 percent of the ice sheet’s mass) each month from 1985 to 2022. Analyzing more than 236,000 satellite images, they manually marked differences along the edges of glaciers and eventually trained algorithms to do the same. From the area measurements, the team could calculate the volume and mass of the changes in ice. Glaciers can lose ice in many ways. One change can happen when large ice chunks break off at the edge, known as calving. They can also lose ice when it melts faster than it can form, causing the end of a glacier to retreat and move to higher elevations. Scientists found that a total of 1,034 gigatons of ice was lost across all glaciers because of this retreat and calving on their peripheries. The loss accelerated since January 2000, with the glaciers losing a total of 42 gigatons each year. It has shown no signs of slowing down. Most striking, nearly every glacier was shrinking — and in every corner of the ice sheet”.

A solar and windfarm in Tangshan City in north China’s Hebei province. Photo: Xinhua/Rex/Shutterstock. |

In January, there were also many political and economic-themed media stories about climate change or global warming that dominated overall coverage this month. For example, Associated Press correspondent Matthew Daly reported, “Climate-altering pollution from greenhouse gases declined by nearly 2% in the United States in 2023, even as the economy expanded at a faster clip, a new report finds. The decline, while “a step in the right direction,’' is far below the rate needed to meet President Joe Biden’s pledge to cut U.S. emissions in half by 2030, compared to 2005 levels, said a report Wednesday from the Rhodium Group, an independent research firm. “Absent other changes,″ the U.S. is on track to cut greenhouse gas emissions by about 40% below 2005 levels by the end of the decade, said Ben King, associate director at Rhodium and lead author of the study. The report said U.S. carbon emissions declined by 1.9% last year. Emissions are down 17.2% from 2005. To reach Biden’s goal, emissions would have to decline at a rate more than triple the 2023 figure and be sustained at that level every year until 2030, he said. Increased economic activity, including more energy production and greater use of cars, trucks and airplanes, can be associated with higher pollution, although there is not always a direct correlation. The U.S. economy grew by a projected 2.4% in 2023, according to the Conference Board, a business research group”.

Also in January, media attention was drawn to renewable energy installation growth as examples of mode-switching sources to reduce emissions-related energy generation. For example, Guardian journalist Jillian Ambrose wrote, “Global renewable energy capacity grew by the fastest pace recorded in the last 20 years in 2023, which could put the world within reach of meeting a key climate target by the end of the decade, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). The world’s renewable energy grew by 50% last year to 510 gigawatts (GW) in 2023, the 22nd year in a row that renewable capacity additions set a new record, according to figures from the IEA. The “spectacular” growth offers a “real chance” of global governments meeting a pledge agreed at the Cop28 climate talks in November to triple renewable energy capacity by 2030 to significantly reduce consumption of fossil fuels, the IEA added. The IEA’s latest report found that solar power accounted for three-quarters of the new renewable energy capacity installed worldwide last year. Most of the world’s new solar power was built in China, which installed more solar power last year than the entire world commissioned the year before, despite cutting subsidies in 2020 and 2021. Record rates of growth across Europe, the US and Brazil have put renewables on track to overtake coal as the largest source of global electricity generation by early 2025, the IEA said. By 2028, it forecasts renewable energy sources will account for more than 42% of global electricity generation. Tripling global renewable energy by the end of the decade to help cut carbon emissions is one of five main climate targets designed to prevent runaway global heating, alongside doubling energy efficiency, cutting methane emissions, transitioning away from fossil fuels, and scaling up financing for emerging and developing economies. Last year’s relatively mild winter and continued declines in power generation from coal-fired plants drove down emissions in the U.S. power and buildings sectors, the report said”.

Young activists participate in a Global Climate Strike near the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment office in Bangkok, Thailand. Photo: Chanat Katanyu. |

Several cultural-themed stories relating to climate change or global warming also ran in January, many were reflections on the previous calendar year. Among them, writing in The Bangkok Post, Moe Moe Lwin wrote, “the cultural wisdom of our ancestors in Southeast Asia contains much knowledge that we urgently need to recollect, or re-learn, in the 21st century if we are to achieve the goal of limiting temperature increase to a rise of 1.5 degrees Celsius. Our ancestors in Southeast Asia knew how to live in harmony with nature, exploiting nature’s bounty without destroying nature. Traditional ways of agriculture, community control of forests and watersheds, building design and construction practices, urban layout, and belief systems can be adapted to modern needs to make present-day living and working much more climate-friendly”. As a second example, New York Times journalists David Gelles and Manuela Andreoni observed, “2023 was a year when climate change felt inescapable. Whether it was the raging wildfires in Canada, the orange skies in New York, the flash floods in Libya or the searing heat in China, the effects of our overheating planet were too severe to ignore. Not coincidentally, it was also a year when climate change started to feel ubiquitous in popular culture. Glossy TV shows, best-selling books, art exhibits and even pop music tackled the subject, often with the kind of nuance and creativity that can help us make sense of the world’s thorniest issues”.

Finally, January 2024 media stories featured several ecological and meteorological dimensions of climate change or global warming. For example, Wall Street Journal reporter Eric Niiler noted, “The record global temperatures that spawned heavy rainfall, disastrous floods and raging wildfires in 2023 will likely continue in 2024, according to the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service. The service is the first analysis to declare—after months of speculation—that 2023 was the hottest year since record-keeping began in the mid-1800s. 2023’s global average temperature, the study found, was 14.98 degrees Celsius, or 58.96 degrees Fahrenheit. That average was 1.48 degrees C, or 2.66 degrees F, hotter than the preindustrial baseline, creeping ever closer to the 1.5 degrees C threshold the world’s nations have agreed to keep warming below to avoid the worst effects of climate change”. As a second example (among many), journalist Jonathan Chadwick from The Daily Mail reported, “Scientists have long suspected it but now it's official – 2023 was the hottest year on record. Last year's global average temperature was 58.96°F (14.98°C), around 0.3°F (0.17°C) higher than the result in 2016, the previous hottest year, experts from the EU's Copernicus climate change programme (CS3) reveal. The scientists have already revealed that last summer was the hottest season on record, while July was the hottest month on record. Experts warn that global temperatures are now close to the 2.7°F (1.5°C) limit – and they point to greenhouse gas emissions as the cause. 2023 has already been dubbed the year Earth suffered the costliest climate disasters like droughts, floods, wildfires and lethal heatwaves, largely due to these emissions”.

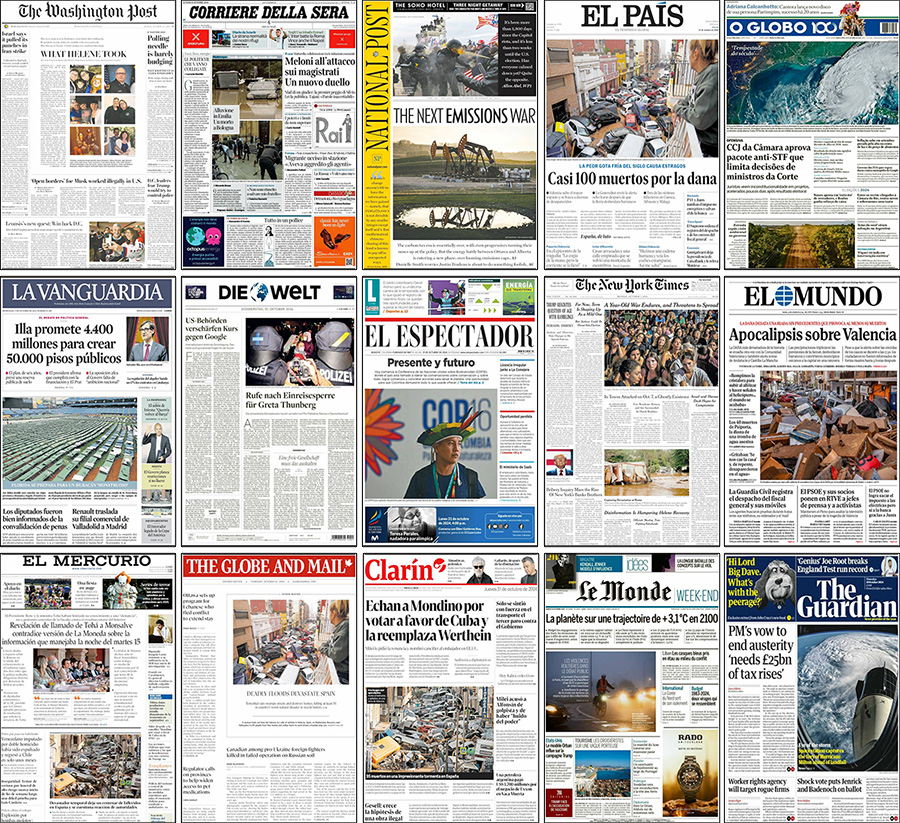

Figure 3. Examples of newspaper front pages with climate change stories in January.

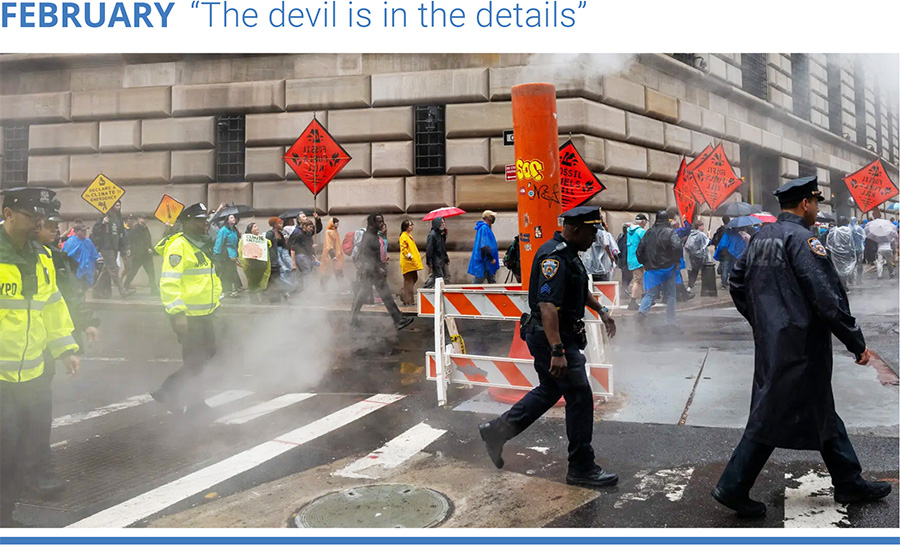

A climate protest in Manhattan’s financial district last year. Several major firms retreated from a global climate coalition in recent days. Photo: Spencer Platt/Getty Images.

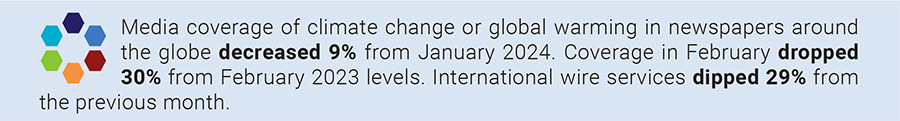

February media coverage of climate change or global warming in newspapers around the globe decreased 9% from January 2024. Moreover, coverage in February dropped 30% from February 2023 levels. Of particular note, in February international wire services dipped 29% from the previous month. Figure 1 shows trends in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – from January 2004 through February 2024.

Figure 1. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in print sources in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through February 2024.

At the regional level, February 2024 coverage decreased in all regions, except in Africa where it increased 39%. It went down in North America (-6%) [see Figure 2], Latin America (-7%), the European Union (EU) (-21%), Oceania (-23%), Asia (-30%), and the Middle East (-64%) compared to the previous month of January.

Figure 2. Newspaper coverage of climate change or global warming in North American newspapers from January 2004 through February 2024.

The Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) team continues to provide international and regional assessments of trends in coverage, along with several country-level appraisals each month. We monitor media coverage of climate change or global warming in 14 languages. We use Factiva, Infomedia, ProQuest, Nifty, BigKind and NexisUni databases for our collective work that currently involved a team of 23 people across 15 institutions in seven countries. Visit our website for open-source datasets and downloadable visuals.

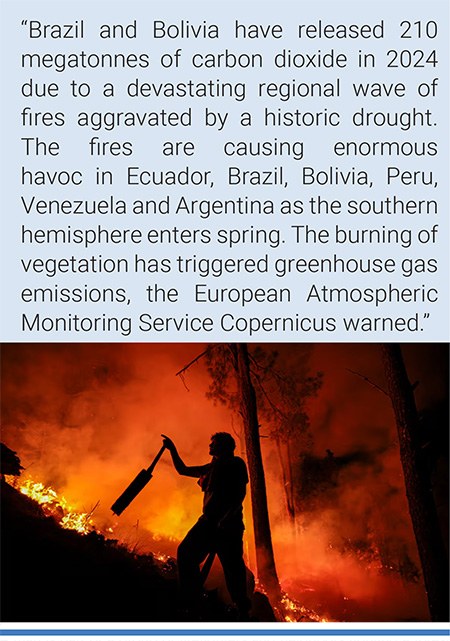

Moving to considerations of content, February 2024 media stories featured several ecological and meteorological dimensions of climate change or global warming. To begin, some exploratory links were made in early February between Chilean wildfires and climate change. For example, New York Times correspondents Annie Correal and John Bartlett noted, “Days after devastating wildfires ripped through Chile’s Pacific Coast, ravaging entire neighborhoods and trapping people fleeing in cars, officials said on Sunday that at least 112 people had been killed and hundreds remained missing and warned that the number of dead could rise sharply…Several other countries in South America have also struggled to contain wildfires. Colombia has seen dozens of fires erupt in recent weeks, including around the capital of Bogotá, as the country has experienced a spell of dry weather. Firefighters have also been battling blazes in Ecuador, Venezuela and Argentina. The cyclical climate phenomenon known as El Niño has exacerbated droughts and high temperatures through parts of the continent, creating conditions that experts say are ripe for forest fires”.

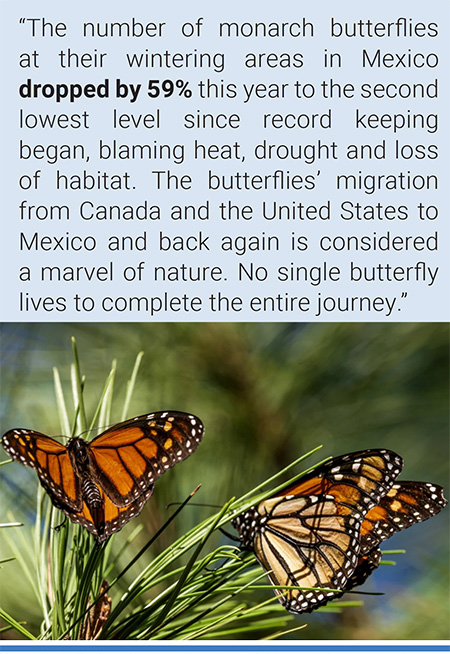

Monarch butterflies land on branches at Monarch Grove Sanctuary in Pacific Grove, Calif., on Nov. 10, 2021. The number of western monarch butterflies overwintering in California dropped 30% from the previous year likely due to a wet winter. Photo: Nic Coury/AP. |

Also in February, changing monarch butterfly migrations earned media attention. For example, Guardian correspondent Catrin Einhorn reported, “The number of monarch butterflies at their overwintering areas in Mexico dropped precipitously this year to the second-lowest level on record, according to an annual survey. The census, considered a benchmark of the species’ health, found that the butterflies occupied only about 2.2 acres of forest in central Mexico, down 59 percent from the prior year. Only the winter of 2013-14 had fewer butterflies. Scientists said the decline appeared to be driven by hot, dry conditions in the United States and Canada that reduced the quality of available milkweed, the only plants monarch caterpillars can eat, as well as the availability of nectar from many kinds of flowers, which they feed on as butterflies”. As a second example, Associated Press correspondent Mark Stevenson noted, “The number of monarch butterflies at their wintering areas in Mexico dropped by 59% this year to the second lowest level since record keeping began, experts said Wednesday, blaming heat, drought and loss of habitat. The butterflies’ migration from Canada and the United States to Mexico and back again is considered a marvel of nature. No single butterfly lives to complete the entire journey. The annual butterfly count doesn’t calculate the individual number of butterflies, but rather the number of acres they cover when they clump together on tree branches in the mountain pine and fir forests west of Mexico City. Monarchs from east of the Rocky Mountains in the United States and Canada overwinter there. Mexico’s Commission for National Protected Areas said the butterflies covered an area equivalent to 2.2 acres (0.9 hectares), down from 5.4 acres (2.21 hectares) last year…Experts said heat and drought appeared to be the main culprits in this year’s drought. “It has a lot to do with climate change,” said Gloria Tavera, the commission’s conservation director”.

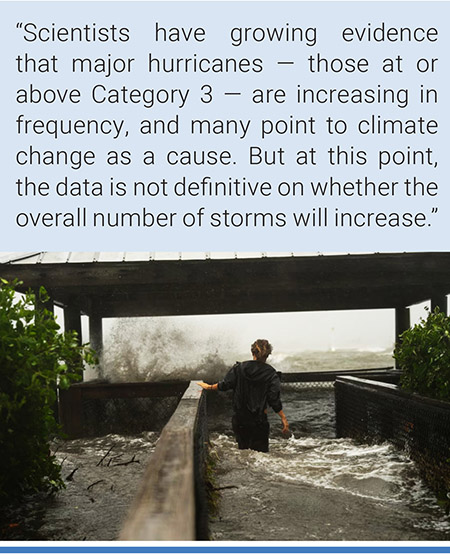

February 2024 coverage also contained many scientific themes in stories during the month. Among them, considerations of hurricanes and climate change made news. For example, Associated Press correspondent Seth Borenstein wrote, “A handful of super powerful tropical storms in the last decade and the prospect of more to come has a couple of experts proposing a new category of whopper hurricanes: Category 6. Studies have shown that the strongest tropical storms are getting more intense because of climate change. So the traditional five-category Saffir-Simpson scale, developed more than 50 years ago, may not show the true power of the most muscular storms, two climate scientists suggest in a Monday study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. They propose a sixth category for storms with winds that exceed 192 miles per hour (309 kilometers per hour). Currently, storms with winds of 157 mph (252 kilometers per hour) or higher are Category 5. The study’s authors said that open-ended grouping doesn’t warn people enough about the higher dangers from monstrous storms that flirt with 200 mph (322 kph) or higher. Several experts told The Associated Press they don’t think another category is necessary. They said it could even give the wrong signal to the public because it’s based on wind speed, while water is by far the deadliest killer in hurricanes”.

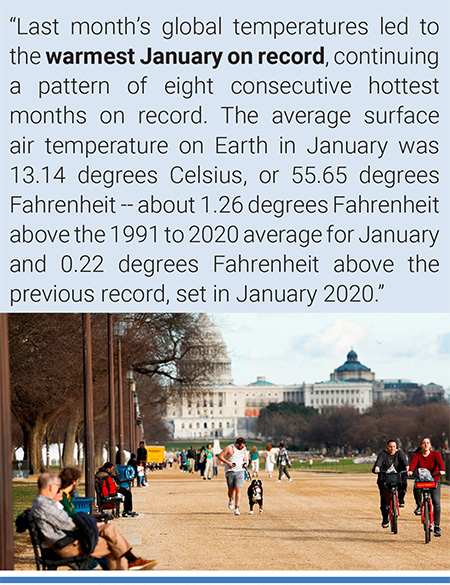

People run on the National Mall, Jan. 26, 2024, in Washington, D.C. Photo: Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images. |

February coverage continued to also track record-breaking warmth on the planet. For example, ABC News reporters Julia Jacobo, Daniel Peck and Ginger Zee noted, “Last month's global temperatures led to the warmest January on record, continuing a pattern of eight consecutive hottest months on record, according to scientists. The average surface air temperature on Earth in January was 13.14 degrees Celsius, or 55.65 degrees Fahrenheit -- about 1.26 degrees Fahrenheit above the 1991 to 2020 average for January and 0.22 degrees Fahrenheit above the previous record, set in January 2020, according to the monthly report released Wednesday by Copernicus, the European Union's climate change service. The month as a whole was 1.66 degrees Celsius (or 2.99 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than an estimate of the January average for 1850 to 1900, the designated pre-industrial reference period, the report, which highlights changes observed in global surface air temperature, sea ice cover and hydrological variables, found. February 2023 through January 2024 was the warmest 12-month stretch on record with the global mean temperature measuring at 1.52 degrees Celsius -- or 2.74 degrees Fahrenheit -- above the 1850 to 1900 pre-industrial average, according to the researchers. The Paris Agreement, a collective climate change agreement among the majority of the world's countries, aims to keep global temperatures below 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming since the Industrial Revolution”.

Further into the month, ecological stories relating to climate change and conservation circulated. For example, CNN journalists Angela Dewan and Rachel Ramirez reported, “Female leatherback turtles are among the world’s most intrepid creatures, making journeys as far as 10,000 miles after nesting to find food in far-away seas. They’ve been known to set off from tropical Southeast Asia up to the cold waters of Alaska, where jellyfish are abundant. But travelling such a long way means encountering threats that can be fatal: fishing nets intended for other species, poachers, pollution and waters warmed by the climate crisis, which force the turtles to travel even further to find their prey. These turtles are just one of hundreds of migratory species — those that make remarkable journeys each year across land, rivers and oceans — that are facing extinction because of human interference, according to a landmark UN agency report published Monday. Of the 1,189 creatures listed by the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals, or CMS, more than one in five are threatened. They include species from all sorts of animal groups — whales, sharks, elephants, wild cats, raptors, birds and insects, among others. Some 44% of those species listed are undergoing population declines, the report said. Most alarming is the state of the world’s migratory fish: Nearly all, 97%, of those listed are threatened with extinction”.

Leatherback turtles encounter many threats during their long migration journeys, and now face extinction due to human activity, a UN report shows. Photo: Samuel J. Coe/Getty Images. |

February featured ongoing cultural-themed stories relating to climate change or global warming as well. To illustrate, a decade-long legal case about defamation of a climate scientist came to a close and it generated several media accounts. For example, Washington Post journalist Dino Grandoni reported, “Michael Mann, a prominent climate scientist, won his long-standing legal battle against two right-wing bloggers who claimed that he manipulated data in his research and compared him to convicted child molester Jerry Sandusky, a major victory for the outspoken researcher. A jury in a civil trial in Washington on Thursday found that the two writers, Rand Simberg and Mark Steyn, defamed and injured the researcher in a pair of blog posts published in 2012, and awarded him more than $1 million. “I hope this verdict sends a message that falsely attacking climate scientists is not protected speech,” Mann said in a statement Mann’s victory comes amid heightened attacks on scientists working not just on climate change but also on vaccines and other issues. But the case was one that some critics worried could have a stifling effect on free speech and open debate in science”.

Last, many political and economic-themed media stories about climate change or global warming were evident in coverage this month. For instance, business commitments to climate action – and backtracking therein – earned media attention in February. For example, New York Times journalist David Gelles noted, “Many of the world’s biggest financial firms spent the past several years burnishing their environmental images by pledging to use their financial muscle to fight climate change. Now, Wall Street has flip-flopped. In recent days, giants of the financial world including JPMorgan, State Street and Pimco all pulled out of a group called Climate Action 100+, an international coalition of money managers that was pushing big companies to address climate issues. Wall Street’s retreat from earlier environmental pledges has been on a slow, steady glide path for months, particularly as Republicans began withering political attacks, saying the investment firms were engaging in “woke capitalism.” But in the past few weeks, things accelerated significantly. BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, scaled back its involvement in the group. Bank of America reneged on a commitment to stop financing new coal mines, coal-burning power plants and Arctic drilling projects. And Republican politicians, sensing momentum, called on other firms to follow suit. The reasons behind the burst of activity reveal how difficult it is proving to be for the business world to make good on its promises to become more environmentally responsible. While many companies say they are committed to combating climate change, the devil is in the details”.

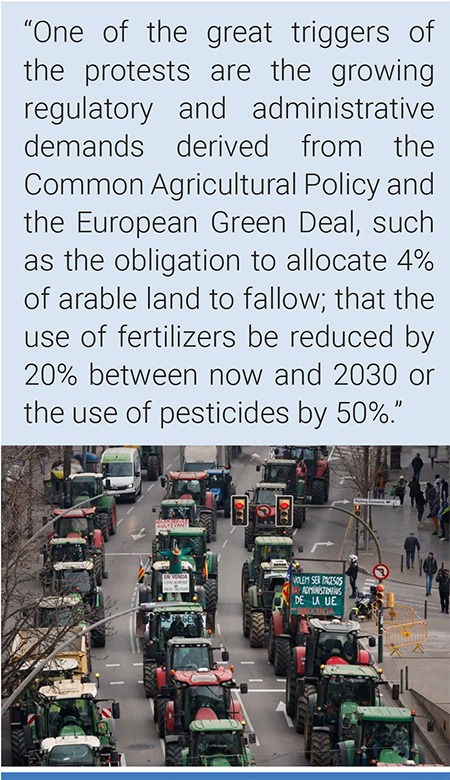

Also in February, protests by European farmers about agricultural policies intersected with climate change in several media portrayals. For example, Expansión journalist J. Díaz wrote, “One of the great triggers of the protests are the growing regulatory and administrative demands derived from the Common Agricultural Policy and the European Green Deal, such as the obligation to allocate 4% of arable land to fallow; that the use of fertilizers be reduced by 20% between now and 2030 or the use of pesticides by 50%”. As a second example, El País María R. Sahuquillo noted, “The farmers' protests in several European countries and, above all, everything, the fear of populism that feeds on the mobilization and cries out against EU regulations, as well as pressure from conservatives, who fear losing ground to the extreme right, push the European Union to reduce its ambition in the green transition. The president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, announced that she is putting aside the pesticide reduction regulations, one of the star formulas within the green pact”.

Farmers protest in Girona, Spain in February 2024. Photo: Albert Gea/Reuters. |

Last, the United Nations environment assembly in Nairobi, Kenya in late February also generated climate-related news. For example, Associated Press correspondent Carlos Mureithi noted, “The world’s top decision-making body on the environment is meeting in Kenya’s capital this week to discuss how countries can work together to tackle environmental crises like climate change, pollution and loss of biodiversity. The meeting in Nairobi is the sixth session of the United Nations Environment Assembly, and governments, civil society groups, scientists and the private sector are attending. At the opening plenary at the U.N. Environment Programme headquarters in Nairobi on Monday, Leila Benali, the president of this year’s assembly, urged members to work toward making “a tangible difference to people’s lives.” “It is up to us to deliver a clean greener and safer future for all people,” she said. Kenya’s environment minister, Soipan Tuya, described this year’s assembly as “an opportunity to inject optimism and restore faith” in the global environmental governance system. At the gathering, member states discuss a raft of draft resolutions on a range of issues that the assembly adopts upon consensus. If a proposal is adopted, it sets the stage for countries to implement what’s been agreed on”. As a second example, Guardian journalist Caroline Kimeu reported, “In an attempt to avoid the “injustices and extractivism” of fossil fuel operations, African leaders are calling for better controls on the dash for the minerals and metals needed for a clean energy transition. A resolution for structural change that will promote equitable benefit-sharing from extraction, supported by a group of mainly African countries including Senegal, Burkina Faso, Cameroon and Chad, was presented at the UN environmental assembly in Nairobi on Wednesday and called for the sustainable use of transitional minerals. “This resolution is crucial for African countries, the environment and the future of our population,” said Jean Marie Bope, a delegate from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which supported the resolution. Demand for transitional minerals and metals, which are used to build renewable energy technologies such as solar plants, windfarms and electric vehicles, has surged over the past decade as the world transitions from fossil fuels. Billions of tonnes of transitional minerals will be needed in the next three decades if the world is to meet its climate goals, according to the United Nations Environment Programme”.

Figure 3. Examples of newspaper front pages with climate change stories in February 2024.

Floods in Rochester, Australia, in January. Photo. Diego Fedele/Getty Images.

March media coverage of climate change or global warming in newspapers around the globe went up 10% from February 2024. However, coverage in March was still down 23% from March 2023 levels. Of particular note, in March international wire services increased 13% from the previous month, while radio coverage dropped 3% from the previous month. Our Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) team has detected that the first three months of global print coverage has seen a drop 20% compared to the first three months of 2023. Figure 1 shows trends in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – from January 2004 through March 2024.

Figure 1. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in print sources in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through March 2024.

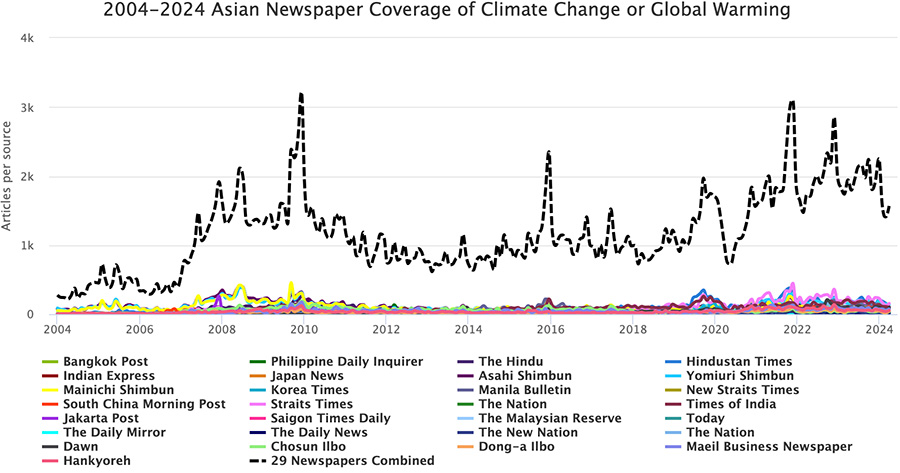

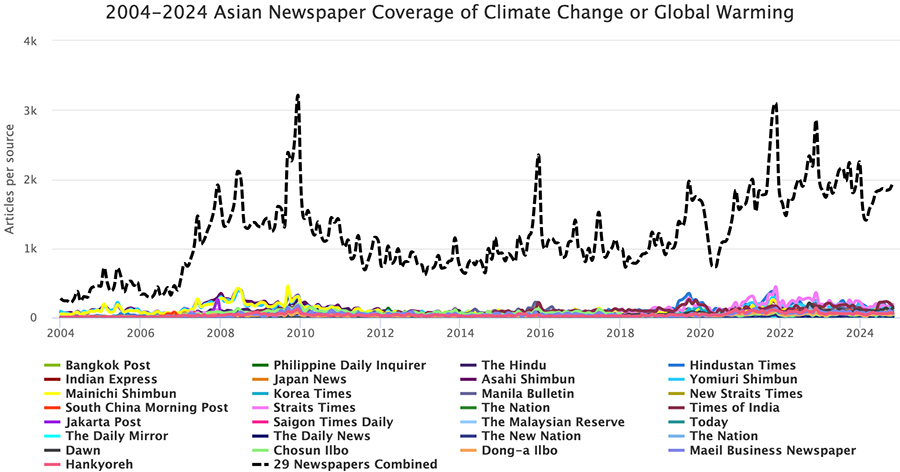

At the regional level, March 2024 coverage increased in all regions from the previous month (except in Africa, which dropped 22%): the European Union (EU) rose 2%, Latin America shot up 9%, North America climbed 12%, Asia coverage increased 13% [see Figure 2], and Middle East and Oceania climate change news each surged 50%.

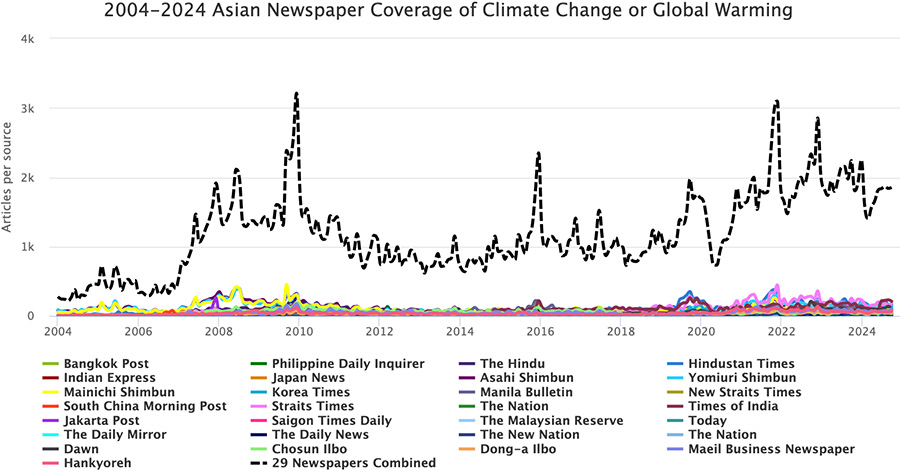

Figure 2. Newspaper coverage of climate change or global warming in Asian newspapers from January 2004 through March 2024.

Moving to considerations of content, March 2024 media stories featured several scientific themes in stories during the month. To begin, the launch of a satellite to track methane pollution and leaks from oil and gas industry activities – called MethaneSAT – earned considerable media attention. For example, Washington Post correspondent Nicolás Rivero reported, “The global crackdown on methane emissions will get a boost from a watchdog satellite built to track and publicly reveal the biggest methane polluters in the oil and gas industry. The satellite launched March 4 on a SpaceX rocket and will begin transmitting data later this year. The satellite, designed by scientists from the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) and Harvard University, will monitor areas that supply 80 percent of the world’s natural gas. Unlike other methane tracking satellites, it will cover a vast territory while also gathering data detailed enough to spot the sources of emissions. “Soon, there will be no place to hide,” said Ben Cahill, a climate expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a national security think tank. “There’s going to be a lot of public data on methane emissions, so companies will have very strong incentives to figure out the problem and fix it.” Methane, a potent greenhouse gas released from farms, landfills and leaky fossil fuel equipment, accounts for nearly a third of global warming. Cutting methane emissions is one of the fastest ways to slow climate change, according to climate scientists, because even though it traps 80 times as much heat in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, it dissipates after about 12 years. Most of the world’s oil and gas companies agreed to slash their methane emissions by more than 80 percent by 2030 at last year’s COP28 climate conference, and policymakers are working to hold them to that promise. U.S. regulators proposed steep fines on methane emissions in January and struck a deal with regulators in Europe, Japan, South Korea and Australia last year to monitor fossil fuel companies’ methane emissions. But so far, it’s been hard to track companies’ progress. There are thousands of oil and gas facilities around the world with countless pieces of equipment that can leak or malfunction and release methane, which is odorless and invisible to the naked eye. Companies and regulators can measure some emissions by installing methane detectors or using planes or drones to fly sensors over a facility, but the data is incomplete and hard to compare between companies. Now, a new generation of satellites, led by MethaneSAT, promises to give a more complete picture of the oil and gas industry’s global methane emissions”.

Aftermath of a wildfire caused by a deadly heatwave near the city of Santa Juana, Chile, in February 2023. Photo: Pablo Hidalgo/EPA. |

As March unfolded, a report released from the World Meteorological Organization – called ‘State of the Global Climate Report’ – outlined impacts of a changing climate, and earned widespread media coverage. For example, Guardian correspondent Ajit Naranjan reported, “The world has never been closer to breaching the 1.5C (2.7F) global heating limit, even if only temporarily, the United Nations’ weather agency has warned. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) confirmed on Tuesday that 2023 was the hottest year on record by a clear margin. In a report on the climate, it found that records were “once again broken, and in some cases smashed” for key indicators such as greenhouse gas pollution, surface temperatures, ocean heat and acidification, sea level rise, Antarctic sea ice cover and glacier retreat. Andrea Celeste Saulo, secretary general of the WMO, said the organisation was now “sounding the red alert to the world”. The report found temperatures near the surface of the earth were 1.45C higher last year than they were in the late 1800s, when people began to destroy nature at an industrial scale and burn large amounts of coal, oil and gas. The error margin of 0.12C in the temperature estimate is large enough that the earth may have already heated 1.5C. But this would not mean world leaders have broken the promise they made in Paris in 2015 to halt global heating to that level by the end of the century, scientists warn, because they measure global heating using a 30-year average rather than counting a spike in a single year. The report documented violent weather extremes – particularly heat – on every inhabited continent. Some of the weather events were made stronger or more likely by climate change, rapid attribution studies have shown”.

Also in March 2024, there were several ongoing media stories relating to ecological and meteorological dimensions of climate change or global warming. At the beginning of the month, the European Union Copernicus Climate Change Service shared news that February 2024 was the hottest February in recorded history. This sparked news reporting. For example, CNN journalist Laura Paddison reported, “Last month was the planet’s hottest February on record, marking the ninth month in a row that global records tumbled, according to new data from Copernicus, the European Union’s climate monitoring service. February was 1.77 degrees Celsius warmer than the average February in pre-industrial times, Copernicus found, and it capped off the hottest 12-month period in recorded history, at 1.56 degrees above pre-industrial levels. It’s yet another grim climate change milestone, as the long-term impacts of human-caused global warming are given a boost by El Niño, a natural climate fluctuation”.

Regionally, ecological and meteorological stories linking to climate change earned attention in March as well. For example, the heat that affected Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo was driven by climate change. Folha de Sao Paulo published a story that noted, “A scientific study carried out by ClimaMeter, a platform of the Paris-Saclay University, evaluated the heat wave that hit part of Brazil from December 15 to 18. March and led to temperatures and thermal sensations reaching new records in cities such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. The study concluded that heat waves similar to the one that occurred in March are 1°C warmer than those previously observed in the country, occurring even at the end of summer. In the assessment of researcher Tommaso Albert, one of the authors of the study, the recent heat wave highlights the profound impact of climate change in Brazil, with increased health risks and important economic implications. In the city of São Paulo, on Saturday, March 16, a temperature of 34.7°C was recorded, the highest recorded in the month in at least 81 years, since the Inmet (National Institute of Meteorology) began compiling the statistics, in 1943. This was the hottest day of 2024 in the capital of São Paulo. In Rio, the next day (March 17), the thermal sensation was record, with 62.3°C recorded at the Guaratiba meteorological station”.

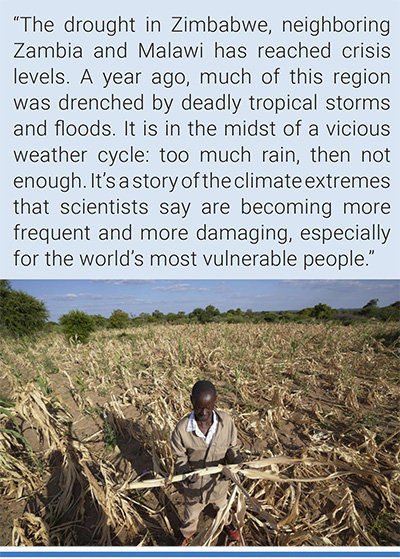

James Tshuma, a farmer in Mangwe district in southwestern Zimbabwe, stands in the middle of his dried up crop field amid a drought, in Zimbabwe, March, 22, 2024. Photo: Tsvangirayi Mukwazhi/AP. |

Meanwhile, on the African continent, climate-related extremes garnered media attention. For example, Associated Press correspondents Faray Mutsaka and Gerald Imray reported, “The drought in Zimbabwe, neighboring Zambia and Malawi has reached crisis levels. Zambia and Malawi have declared national disasters. Zimbabwe could be on the brink of doing the same. The drought has reached Botswana and Angola to the west, and Mozambique and Madagascar to the east. A year ago, much of this region was drenched by deadly tropical storms and floods. It is in the midst of a vicious weather cycle: too much rain, then not enough. It’s a story of the climate extremes that scientists say are becoming more frequent and more damaging, especially for the world’s most vulnerable people”.

In Europe, episodes of severe droughts impacted the region, and earned media attention. For example, according to an editorial in La Vanguardia, "in Catalonia, the drought is wreaking havoc in the Penedès. There is a danger that a third of the 32,000 hectares of vineyards in the Alt and Baix Penedès will not sprout this year, or that, if they do it, they do not produce production. Last year some winegrowers already lost a large part of their production and now it will be much worse. It was feared that climate change could be a threat to the vineyards of these regions. But everything has been brought forward with a lack of water and unprecedented high temperatures. The recent rains have been clearly insufficient."

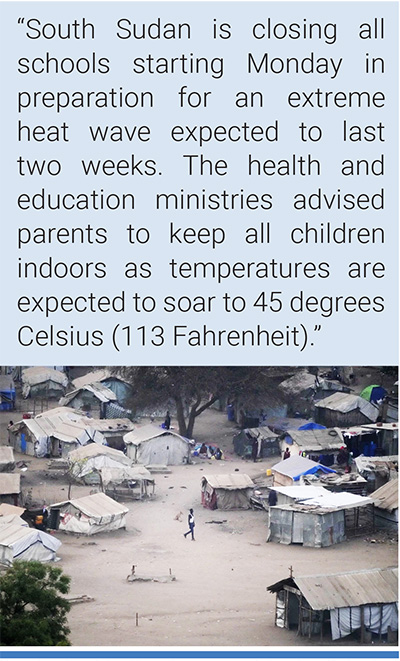

Media coverage in March 2024 also featured related and ongoing cultural-themed stories relating to climate change or global warming as well. To illustrate, there was reporting on how heat waves across several regions of the planet impacted everyday lives and livelihoods. For example, Associated Press correspondent Deng Machol reported from Sudan, noting, “South Sudan is closing all schools starting Monday in preparation for an extreme heat wave expected to last two weeks. The health and education ministries advised parents to keep all children indoors as temperatures are expected to soar to 45 degrees Celsius (113 Fahrenheit). They warned that any school found open during the warning period would have its registration withdrawn, but the statement issued late Saturday didn’t specify how long schools would remain shuttered. The ministries said they “will continue to monitor the situation and inform the public accordingly.” Resident Peter Garang, who lives in the capital, Juba, welcomed the decision. He said “schools should be connected to the electricity grid” to enable the installation of air conditioners. South Sudan, one of the world’s youngest nations, is particularly vulnerable to climate change with heat waves common but rarely exceeding 40 C (104 F). Civil conflict has plagued the east African country which also suffered from drought and flooding, making living conditions difficult for residents. The World Food Program in its latest country brief said South Sudan “continues to face a dire humanitarian crisis” due to violence, economic instability, climate change and an influx of people fleeing the conflict in neighboring Sudan. It also stated that 818,000 vulnerable people were given food and cash-based transfers in January”.

People stand by their houses in Juba, South Sudan. Photo: Gregorio Borgia/AP. |

Meanwhile, Associated Press journalist Sibi Arasu reported from India, “Bhavani Mani Muthuvel and her family of nine have around five 20-liter (5-gallon) buckets worth of water for the week for cooking, cleaning and household chores. “From taking showers to using toilets and washing clothes, we are taking turns to do everything,” she said. It’s the only water they can afford. A resident of Ambedkar Nagar, a low-income settlement in the shadows of the lavish headquarters of multiple global software companies in Bengaluru’s Whitefield neighborhood, Muthuvel is normally reliant on piped water, sourced from groundwater. But it’s drying up. She said it’s the worst water crisis she has experienced in her 40 years in the neighborhood. Bengaluru in southern India is witnessing an unusually hot February and March, and in the last few years, it has received little rainfall in part due to human-caused climate change. Water levels are running desperately low, particularly in poorer areas, resulting in sky-high costs for water and a quickly dwindling supply”.

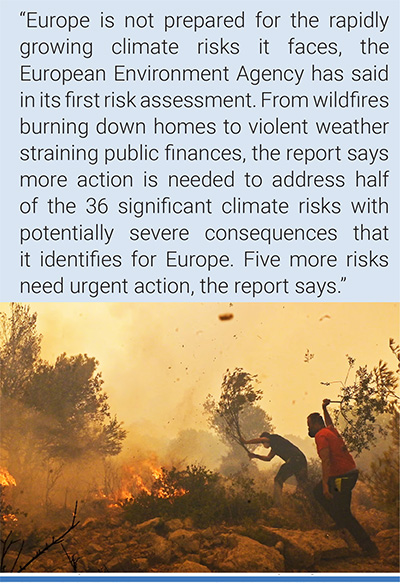

Meanwhile, in Europe there were stories of increasing climate-related risks for everyday citizens of the region. For example, Guardian correspondent Ajit Niranjan reported, “Europe is not prepared for the rapidly growing climate risks it faces, the European Environment Agency (EEA) has said in its first risk assessment. From wildfires burning down homes to violent weather straining public finances, the report says more action is needed to address half of the 36 significant climate risks with potentially severe consequences that it identifies for Europe. Five more risks need urgent action, the report says. “Our new analysis shows that Europe faces urgent climate risks that are growing faster than our societal preparedness,” said Leena Ylä-Mononen, the EEA’s executive director. The report looks at how severe the climate threats are and how well prepared Europe is to deal with them. It says the most pressing risks – which are growing worse as fossil fuel pollution heats the planet – are heat stress, flash floods and river floods, the health of coastal and marine ecosystems, and the need for solidarity funds to recover from disasters. When the researchers reassessed six of the risks for southern Europe, which they described as a “hotspot” region, they found urgent action was also needed to keep crops safe and to protect people, buildings and nature from wildfires”. As a second example, Associated Press journalists Carlos Mureithi and Dana Beltaji wrote, “Europe is facing growing climate risks and is unprepared for them, the European Environment Agency said in its first-ever risk assessment for the bloc…The agency said Europe is prone to more frequent and more punishing weather extremes — including increasing wildfires, drought, more unusual rainfall patterns and flooding — and it needs to immediately address them in order to protect its energy, food security, water and health. These climate risks “are growing faster than our societal preparedness,” Leena Ylä-Mononen, the EEA’s executive director, said in a statement. The report identified 36 major climate risks for the continent, such as threats to ecosystems, economies, health and food systems, and found that more than half demand greater action now. It classified eight as needing urgent attention – like conserving ecosystems, protecting people against heat, protecting people and infrastructure from floods and wildfires, and securing relief funds for disasters”.

Residents help firefighters try to extinguish a wildfire burning near Athens, in July 2023. Photo: Miloš Bičanski/Getty Images. |

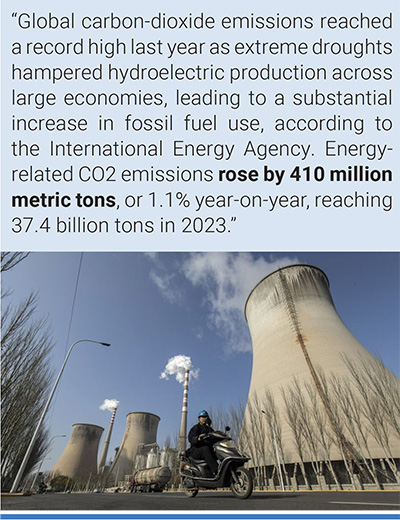

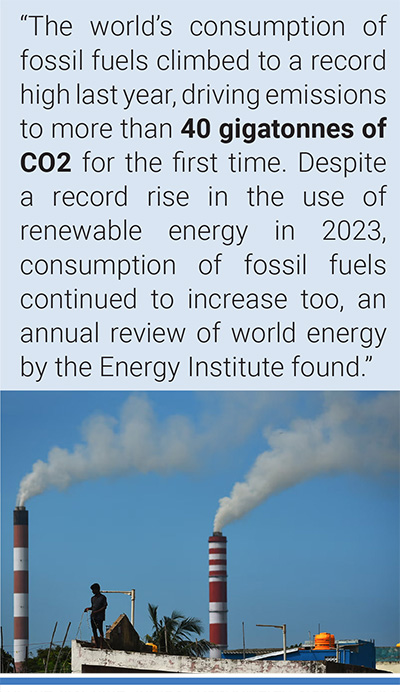

Last, many political and economic-themed media stories about climate change or global warming were evident in March 2024 coverage. For instance, International Energy Agency statements regarding the need for greater clean energy investments and larger emissions cuts grabbed media attention. For example, Wall Street Journal correspondent Giulia Petroni wrote, “Global carbon-dioxide emissions reached a record high last year as extreme droughts hampered hydroelectric production across large economies, leading to a substantial increase in fossil fuel use, according to the International Energy Agency. Energy-related CO2 emissions rose by 410 million metric tons, or 1.1% year-on-year, reaching 37.4 billion tons in 2023, the Paris-based organization said Friday in its latest report. The use of fossil fuels to replace hydropower accounted for over 40% of the increase. In India and China, heavy reliance on coal and higher electricity demand following the postpandemic economic recovery pushed emissions significantly higher, offsetting reductions in other economies. Emissions rose more than 7% on year in India, where a weaker monsoon season drove hydropower output lower. In China, emissions from energy combustion rose by 5.2% to 12.6 billion tons—by far the largest on a global scale despite the country’s leading position in the deployment of clean-energy technology. The agency’s report refers to emissions from all uses of fossil fuels for energy purposes and industrial processes. In advanced economies instead, emissions fell 4.5% to a 50-year low last year, supported by a stronger deployment of renewables and energy-efficiency measures, but also weaker industrial production and milder weather in some regions resulting in lower energy demand. According to the agency, electricity generation from renewable sources and nuclear power in those economies reached 50% of total generation. Renewables alone accounted for 34% of electricity output, while the share of coal fell to a historic low of 17%. In the European Union, emissions from energy combustion fell by almost 9% in 2023 driven by a surge in renewables generation and drop in both coal and gas generation, despite economic growth of around 0.7%. In the U.S., emissions fell 4.1% on higher electricity generation from renewables and gas rather than coal, in spite of economic growth of 2.5%. Still, the deployment of clean-energy sources remains overly concentrated in advanced economies and China, the IEA said, calling for greater international efforts to increase investment and deployment in emerging and developing economies. Overall, the pace of global emissions growth slowed down in 2023, supported by the expansion of renewable energy and electric vehicles, the IEA said. In 2022, energy-related CO2 emissions rose by 1.3%”.

Smoke stacks in Liaoning province, China. Photo: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg News. |

In the US, there was abundant media coverage in late March about the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) release of transportation-related rules to reduce emissions from vehicles. For example, Washington Post journalist Maxine Joselow wrote, “Rayan Makarem worries about the air that his 2-year-old daughter breathes. More than 100 diesel-powered trucks rumble through their neighborhood every half an hour, spewing harmful pollutants linked to asthma and other health conditions. The pollution in their community — and others like it nationwide — will be curbed under a climate change rule the Environmental Protection Agency finalized Friday. The rule will require manufacturers to slash emissions of greenhouse gases from new trucks, delivery vans and buses. Those limits, in turn, will reduce deadly particulate matter and lung-damaging nitrogen dioxide from such vehicles…The EPA rule follows strict emissions limits for gas-powered cars aimed at accelerating the nation’s halting transition to electric vehicles. It marks the first time in more than two decades that the federal government has cracked down on pollution from diesel trucks. The rule doesn’t go as far as Makarem and other environmental justice advocates would like. The Moving Forward Network had urged the EPA to require all new trucks to be zero-emission by 2035. Yet EPA officials said the rule will not mandate the adoption of a particular zero-emission technology. Rather, it will require manufacturers to reduce emissions by choosing from several cleaner technologies, including electric trucks, hybrid trucks and hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles. Still, the rule stands to benefit poor, Black and Latino communities that are disproportionately exposed to diesel exhaust from highways, ports and sprawling distribution centers. These communities suffer higher rates of asthma, heart disease and premature deaths from air pollution”. Elsewhere, New York Times correspondents Coral Davenport and Jack Ewing reported, “The Biden administration on Friday announced a regulation designed to turbocharge sales of electric or other zero-emission heavy vehicles, from school buses to cement mixers, as part of its multifront attack on global warming. The Environmental Protection Agency projects the new rule could mean that 25 percent of new long-haul trucks, the heaviest on the road, and 40 percent of medium-size trucks, like box trucks and landscaping vehicles, could be nonpolluting by 2032. Today, fewer than 2 percent of new heavy trucks sold in the United States fit that bill. The regulation would apply to more than 100 types of vehicles including tractor-trailers, ambulances, R.V.s, garbage trucks and moving vans. The rule does not mandate the sales of electric trucks or any other type of zero or low-emission truck. Rather, it increasingly limits the amount of pollution allowed from trucks across a manufacturer's product line over time, starting in model year 2027. It would be up to the manufacturer to decide how to comply. Options could include using technologies like hybrids or hydrogen fuel cells or sharply increasing the fuel efficiency of the conventional trucks. The truck regulation follows another rule made final last week that is designed to ensure that the majority of new passenger cars and light trucks sold in the United States are all-electric or hybrids by 2032, up from just 7.6 percent last year. Together, the car and truck rules are intended to slash carbon dioxide pollution from transportation, the nation’s largest source of the fossil fuel emissions that are driving climate change and that helped to make 2023 the hottest year in recorded history. Electric vehicles are central to President Biden’s strategy to confront global warming, which calls for cutting the nation’s emissions in half by the end of this decade”.

Figure 3. Examples of newspaper front pages with climate change stories in March 2024.

The historical record encompasses 122 entities linked to 72% of all the fossil fuel and cement CO2 emissions since the start of the industrial revolution. Photo: Nick Oxford/Reuters.

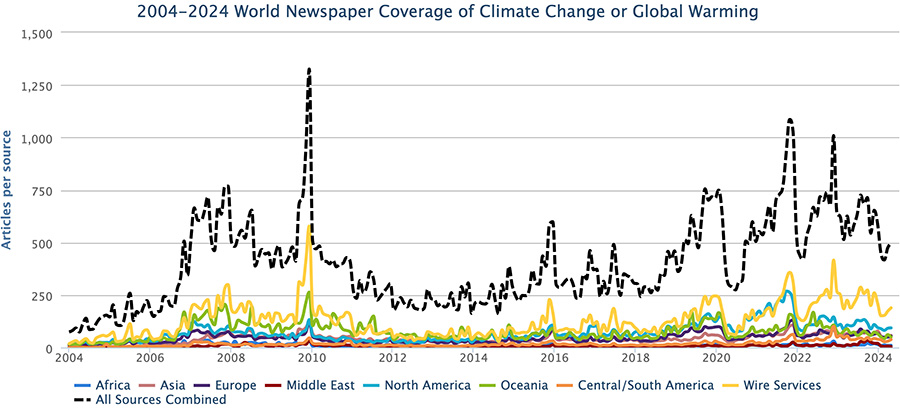

April media coverage of climate change or global warming in newspapers around the globe rose 6% from March 2024. Meanwhile, coverage in April 2024 dropped 7% from April 2023 levels. Of particular note, in April international wire services increased 9% from the previous month, as radio coverage also went up 4% from the previous month. Figure 1 shows trends in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – from January 2004 through April 2024.

Figure 1. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in print sources in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through April 2024.

At the regional level, April 2024 coverage increased in North America (+2%), Asia (+6%), the European Union (EU) (+10%), Africa (+11%), and Latin America (+26%) compared to the previous month of March. Meanwhile, coverage decreased in Oceania (-19%), and the Middle East (-36%).

Figure 2. US television coverage of climate change or global warming from January 2000 through April 2024.

Our Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) team continues to provide international and regional assessments of trends in coverage, along with country-level appraisals each month. Visit our website for open-source datasets and downloadable visuals.

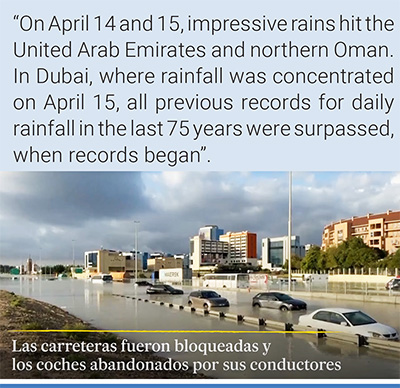

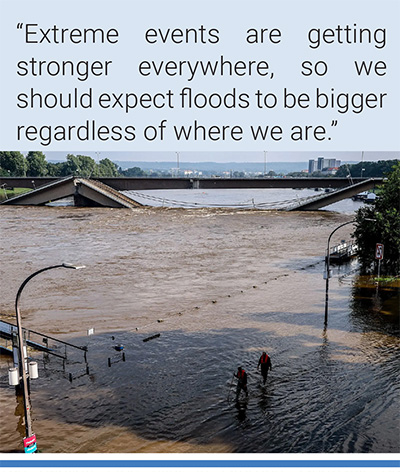

Moving to the content of April 2024 coverage, there were many media stories relating to ecological and meteorological dimensions of climate change or global warming. At the beginning of the month, flooding in the Middle East – with connections to a changing climate – pervaded international media attention. For example, CNN correspondents Nadeen Ebrahim, Mary Gilbert and Brandon Miller reported, “Chaos ensued in the United Arab Emirates after the country witnessed the heaviest rainfall in 75 years, with some areas recording more than 250 mm (around 10 inches) of precipitation in fewer than 24 hours, the state’s media office said in a statement Wednesday. The rainfall, which flooded streets, uprooted palm trees and shattered building facades, has never been seen in the Middle Eastern nation since records began in 1949. In the popular tourist destination Dubai, flights were canceled, traffic came to a halt and schools closed. One-hundred millimeters (nearly 4 inches) of rain fell over the course of just 12 hours on Tuesday, according to weather observations at the airport – around what Dubai usually records in an entire year, according to United Nations data. The rain fell so heavily and so quickly that some motorists were forced to abandon their vehicles as the floodwater rose and roads turned into rivers. Extreme rainfall events like this are becoming more common as the atmosphere warms due to human-driven climate change. A warmer atmosphere is able to soak up more moisture like a towel and then ring it out in the form of flooding rainfall. The weather conditions were associated with a larger storm system traversing the Arabian Peninsula and moving across the Gulf of Oman. This same system is also bringing unusually wet weather to nearby Oman and southeastern Iran. In Oman, at least 18 were killed in flash floods triggered by heavy rain, the country’s National Committee for Emergency Management said. Casualties included schoolchildren, according to Oman’s state news agency”.

A man cools off in street tap water during the heatwave in West Bengal, India. Photo: Jit Chattopadhyay/SOPA Images/REX/Shutterstock. |

Elsewhere, New York Times journalists Zia ur-Rehman and Christina Goldbaum noted, “A deluge of unseasonably heavy rains has lashed Pakistan and Afghanistan in recent days, killing more than 130 people across both countries, with the authorities forecasting more flooding and rainfall, and some experts pointing to climate change as the cause. In Afghanistan, at least 70 people have been killed in flash floods and other weather-related incidents, while more than 2,600 homes have been destroyed or damaged, according to Mullah Janan Sayeq, a spokesman for the Ministry of Disaster Management. At least 62 people have died in the storms in neighboring Pakistan, which has been hammered by rainfall at nearly twice the average rate for this time of year, according to Pakistani officials. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, the Pakistani region bordering Afghanistan, appears to be the hardest hit. Flash floods and landslides caused by torrential rains have damaged homes and destroyed infrastructure. Photos and videos from the province show roads turned into raging rivers, and homes and bridges being swept away”.

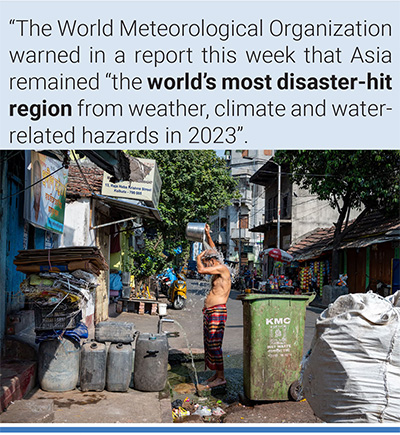

As the month of April continued, a heat wave in Southeast Asia – with connections to climate change – made news. For example, Guardian correspondent Rebecca Ratcliffe reported, “Millions of people across South and Southeast Asia are facing sweltering temperatures, with unusually hot weather forcing schools to close and threatening public health. Thousands of schools across the Philippines, including in the capital region Metro Manila, have suspended in-person classes. Half of the country’s 82 provinces are experiencing drought, and nearly 31 others are facing dry spells or dry conditions, according to the UN, which has called for greater support to help the country prepare for similar weather events in the future. The country’s upcoming harvest will probably be below average, the UN said. April and May are usually the hottest months in the Philippines and other countries in south-east Asia, but temperatures this year have been worsened by the El Niño event, which brings hotter, drier conditions to the region. Thai authorities said 30 people had been killed by heatstroke so far this year, and warned people to avoid outdoor activities. Demand for electricity soared to a new high on Monday night of 35,830 megawatts, as people turned to air conditioning for relief, local media reported…The World Meteorological Organization warned in a report this week that Asia remained “the world’s most disaster-hit region from weather, climate and water-related hazards in 2023”. Floods and storms caused the highest number of reported casualties and economic losses, it said, while the impact of heatwaves became more severe. Last year, severe heatwaves in India in April and June caused about 110 reported deaths due to heatstroke. “A major and prolonged heatwave affected much of South-east Asia in April and May, extending as far west as Bangladesh and Eastern India, and north to southern China, with record-breaking temperatures,” WMO said. Human-caused climate breakdown is supercharging extreme weather across the world, driving more frequent and more deadly disasters from heatwaves to floods to wildfires. At least a dozen of the most serious events of the last decade would have been all but impossible without human-caused global heating”. Meanwhile, New York Times correspondent Saif Hasnat and Mike Ives noted, “Asia’s heat wave isn’t happening in a meteorological vacuum. Last year was Earth’s warmest by far in a century and a half. And the region is in the middle of an El Niño cycle, a climate phenomenon that tends to create warm, dry conditions in Asia. Asia’s summer monsoon will bring relief, but it’s still weeks away. In Thailand on Monday, the national forecast called for “hot to very hot weather.” It put the chances of rain in Bangkok, the capital, at zero percent”. Reporting from The Daily Star in Bangladesh also documented, “At least 23 days of this month were heatwave days, which equals the record set in 2019 for the entire year…Recently published BMD report "Changing Climate of Bangladesh" observed that the minimum and maximum temperatures increased in the country but the maximum temperatures increased more rapidly”.

Screenshot from video on El País. Credit EPV. |

Several other meteorological themed media stories were published on climate change or global warming. For example, experts blame warming waterspouts of water in Dubai. El País journalist Manuel Planelles wrote, “On April 14 and 15, impressive rains hit the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and northern Oman. In Dubai, where rainfall was concentrated on April 15, all previous records for daily rainfall in the last 75 years were surpassed, when records began, according to the Government of this country (…) “Cloud seeding did not have a significant influence on the event,” concludes a report prepared by a group of scientists from World Weather Attribution (WWA). In this case, the WWA considers that warming has contributed to making these rains stronger”.

Over in Europe, La Vanguardia journalist Antonio Cerrillo noted, “The year 2023 was the first or second warmest year in Europe as a whole since records have been recorded (depending on whether Greenland data is taken into account). The average temperature in the Old Continent last year was 1ºC higher than the 1991-2020 average, according to the report on the climate in Europe from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the EU Copernicus program. But the most relevant thing is that, while the entire planet records a temperature rise of 1.4ºC compared to the time pre-industrial, in Europe the rise is 2.6ºC. Why that difference? Since the 1980s, Europe has been warming twice as much as the world average. It is the continent that most rapidly experiences this process. This is mainly due to the greater proportion of European land in the Arctic, the fastest warming region on Earth (3ºC since the 1970s)”.

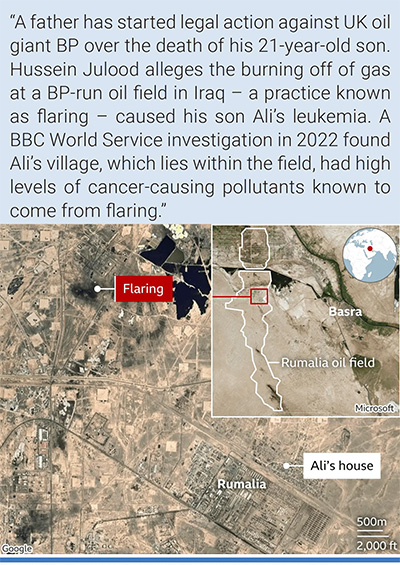

Ali's house lies within the boundaries of Rumaila oil field. Credit: BBC. |

Some media coverage in the month of April 2024 featured related and ongoing cultural-themed stories relating to climate change or global warming. To illustrate, connections between climate change and public health were documented in several news stories. For example, BBC journalists Esme Stallard and Owen Pinnell reported, “A father has started legal action against UK oil giant BP over the death of his 21-year-old son. Hussein Julood alleges the burning off of gas at a BP-run oil field in Iraq – a practice known as flaring – caused his son Ali's leukemia. A BBC World Service investigation in 2022 found Ali's village, which lies within the field, had high levels of cancer-causing pollutants known to come from flaring. BP said "we understand the concerns" and are supporting change. The case is believed to be the first time an individual has started legal action against a major oil firm over its flaring practices…The deadly impact of the oil giants' toxic air pollution on children and the planet is revealed in this BBC News Arabic investigation from the front line of climate change in Iraq”.

Next, several political and economic-themed media stories about climate change or global warming comprised a subset of April 2024 coverage. In another instance, there were stories across Europe about a court ruling in Switzerland that human rights were violated by failing to adequately address climate change. For example, BBC correspondent Georgina Rannard reported, “A group of older Swiss women have won the first ever climate case victory in the European Court of Human Rights. The women, mostly in their 70s, said that their age and gender made them particularly vulnerable to the effects of heatwaves linked to climate change. The court said Switzerland's efforts to meet its emission reduction targets had been woefully inadequate”. Elsewhere, Wall Street Journal reporter Yusuf Khan noted, “The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) on Tuesday ruled in favor of a group of elderly Swiss women who argued that their government isn’t doing enough to fight climate change, putting them at risk of death from heat waves. In what is being seen as a landmark case in the fight against climate change, the ECHR ruled 16 votes to one in favor of the women’s’ claims that Swiss authorities aren’t taking sufficient action to mitigate the effects of climate change, under the European Convention on Human Rights. In particular, the court found that the convention “encompasses a right to effective protection by the State authorities from the serious adverse effects of climate change on lives, health, well-being and quality of life.” Given this, it said current efforts by the Swiss government were lacking, including a failure to quantify national greenhouse-gas-emission limitations. More than 2,000 women from across Switzerland brought the claim. The ruling sets an important precedent for governments in their bid to protect citizens against the effects of climate change. Lawyers are suggesting it could influence legislation in other European countries. It is the first time the powerful court has ruled on global warming”. As a third example, El País journalist Manuel Planelles reported, “Around 2,000 women banded together to take their government to court because they claimed its lack of action puts them at risk of dying, for example, during a heat wave. It is the first time that this court has ruled on the lack of action by state authorities against global warming. The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) does not include any right to a healthy environment as such. But the ECHR has issued several rulings in this environmental matter, understanding that the exercise of certain rights of the convention may be undermined by the existence of damage to the environment and exposure to environmental risks. This is the route used by the complainants, who have received the support of environmental organizations, to reach this international court”.

A woman protects herself from the sun in São Paulo, Brazil. Photo: Sebastião Moreira/EPA. |

Last, April 2024 media stories featured several scientific themes in stories during the month. To begin, news broke from a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) report that carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide gases reached record levels in the atmosphere. For example, Guardian correspondent Oliver Milman wrote, “The levels of the three most important heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere reached new record highs again last year, US scientists have confirmed, underlining the escalating challenge posed by the climate crisis. The global concentration of carbon dioxide, the most important and prevalent of the greenhouse gases emitted by human activity, rose to an average of 419 parts per million in the atmosphere in 2023 while methane, a powerful if shorter-lasting greenhouse gas, rose to an average of 1922 parts per billion. Levels of nitrous oxide, the third most significant human-caused warming emission, climbed slightly to 336 parts per billion. Through the burning of fossil fuels, animal agriculture and deforestation, the world’s CO2 levels are now more than 50% higher than they were before the era of mass industrialization. Methane, which comes from sources including oil and gas drilling and livestock, has surged even more dramatically in recent years, NOAA said, and now has atmospheric concentrations 160% larger than in pre-industrial times. NOAA said the onward march of greenhouse gas levels was due to the continued use of fossil fuels, as well as the impact of wildfires, which spew carbon-laden smoke into the air. Nitrous oxide, meanwhile, has risen due to the widespread use of nitrogen fertilizer and the intensification of agriculture”.

Then in mid-April a new study linking lost global income and global warming earned news attention. For example, Associated Press journalist Seth Borenstein wrote, “Climate change will reduce future global income by about 19% in the next 25 years compared to a fictional world that’s not warming, with the poorest areas and those least responsible for heating the atmosphere taking the biggest monetary hit, a new study said. Climate change’s economic bite in how much people make is already locked in at about $38 trillion a year by 2049, according to Wednesday’s study in the journal Nature by researchers at Germany’s Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. By 2100 the financial cost could hit twice what previous studies estimate. “Our analysis shows that climate change will cause massive economic damages within the next 25 years in almost all countries around the world, also in highly-developed ones such as Germany and the U.S., with a projected median income reduction of 11% each and France with 13%,” said study co-author Leonie Wenz, a climate scientist and economist. These damages are compared to a baseline of no climate change and are then applied against overall expected global growth in gross domestic product, said study lead author Max Kotz, a climate scientist. So while it’s 19% globally less than it could have been with no climate change, in most places, income will still grow, just not as much because of warmer temperatures”.

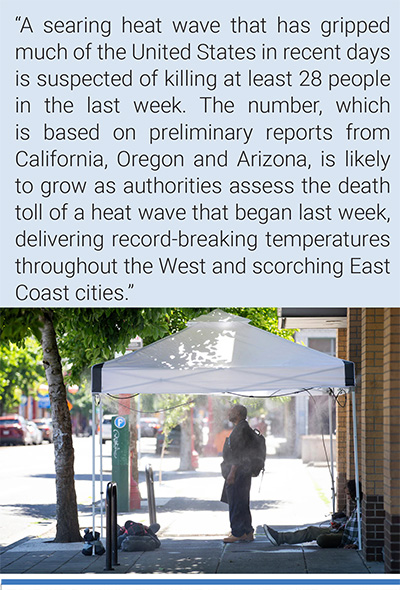

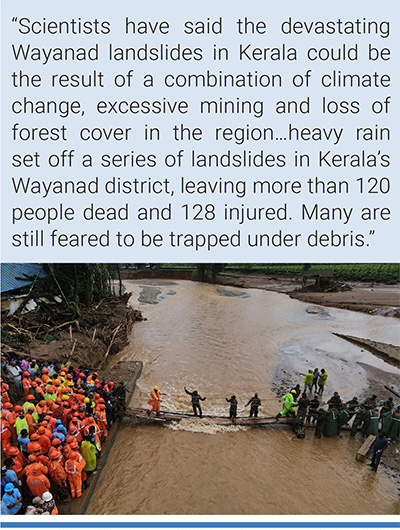

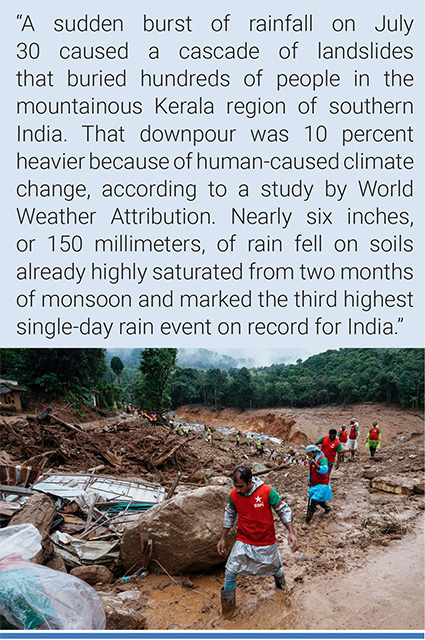

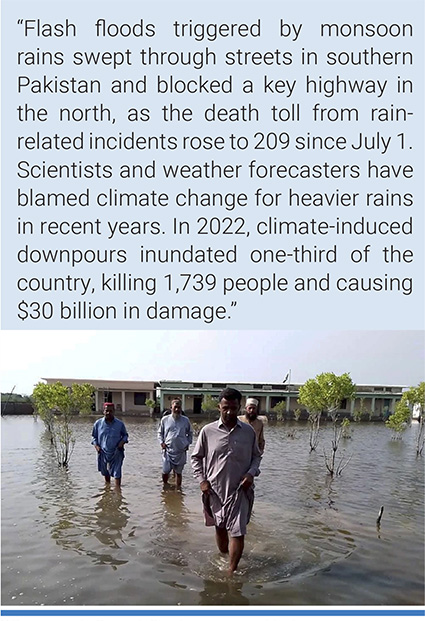

People watch the sunset at a park on an unseasonably warm day, Feb. 25, 2024, in Kansas City, MO. Photo: Charlie Riedel/AP. |