Monthly Summaries

Issue 97, January 2025 | "We have no time to lose"

[DOI]

Image credit: BBC.

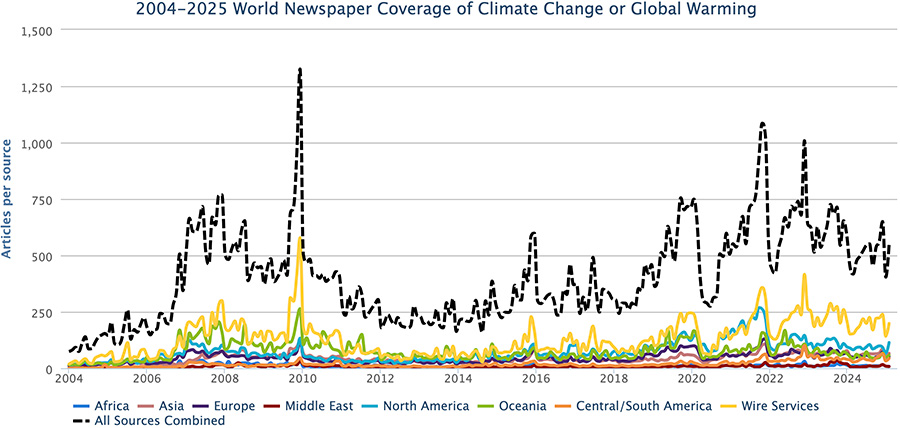

January media coverage of climate change or global warming in newspapers around the globe increased 27% from December 2024. Furthermore, coverage in January 2025 went up 15% from January 2024. In January, international wire service coverage increased 40% from the month earlier (December) and 31% from the previous year (January 2024). Figure 1 shows trends in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – across 21 years, from January 2004 through January 2025.

Figure 1. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in print sources in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through January 2025.

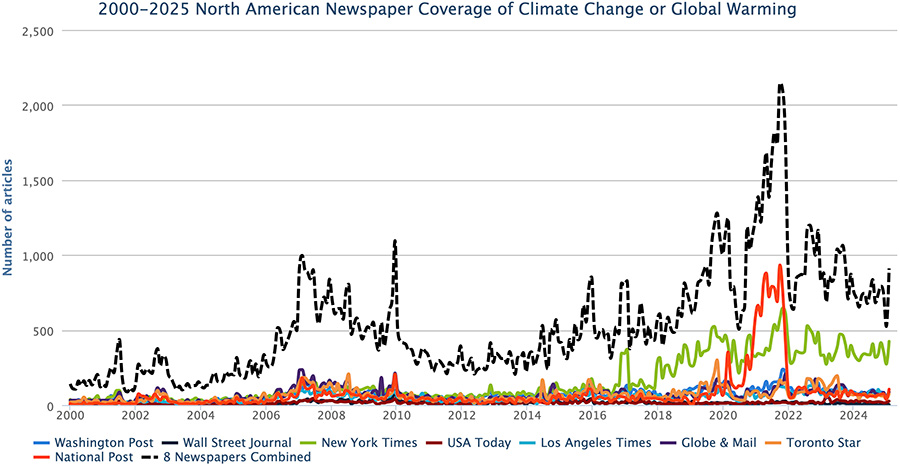

At the regional level, January 2025 coverage went up in Asia (+10%), Oceania (+21%), the European Union (EU) (+30%), and Latin America (+34%) while surging in North America (+74%) (see Figure 2). The large increase in media attention is attributed largely to a combination of devastating wildfires in the Los Angeles (LA), California (CA) area – with connections made to climate change or global warming – and the climate policy implications of the incoming United States (US) Trump Administration (such as the announced withdrawal from the Paris Agreement and the Federal funding for climate-related initiatives). Meanwhile, coverage diminished in Africa (-7%), and the Middle East (-14%) in January 2025 compared to the previous month. Comparing January 2025 to January 2024 levels of coverage, numbers were up in all regions except Africa (-7%), with coverage in the EU just about the same (+0.2%): the Middle East (+9%), Oceania (+14%), Latin America (+19%), Asia (+21%), and North America (+27%).

Figure 2. Coverage of climate change or global warming in North America from January 2000 through January 2025: Washington Post (US), Wall Street Journal (US), New York Times (US), USA Today (US), Los Angeles Times (US), Globe & Mail (Canada), Toronto Star (Canada), National Post (Canada).

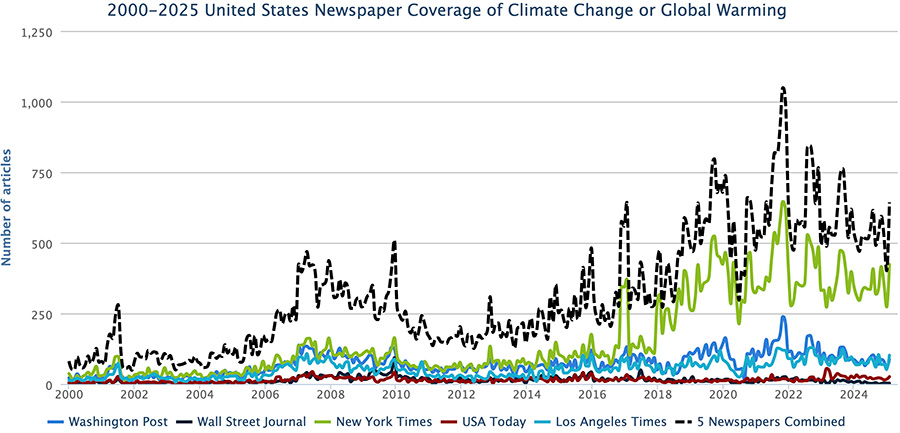

Among our country-level monitoring, in January US print coverage (see Figure 3) went up 60% from December 2024 levels of coverage. Coverage in The Wall Street Journal held steady, while coverage was up 53% at USA Today, up 54% at The Washington Post, and up 55% in The New York Times, while doubling in The Los Angeles Times. At the same time, US television coverage jumped 168% in January. Storylines about the first steps of the US Trump Administration regarding climate policy, regulatory and funding rollbacks and the devastating climate change-influenced LA wildfires contributed to these increases.

Figure 3. US newspapers’ – Los Angeles Times, New York Times, USA Today, Wall Street Journal, and Washington Post – coverage of climate change or global warming from January 2000 through January 2025.

Off-shore oil platform in the Santa Barbara channel, off Ventura, California. Photo credit: Russ Bishop/Alamy. |

To start our analysis of themes of coverage, political and economic-themed media stories about climate change or global warming fought for attention in various outlets in January. Stories about the US presidential handoff from President Joe Biden to President Donald Trump – with their significantly contrasting views about climate policy – were prominent in domestic as well as international outlets. For example, just before leaving office the White House announced that President Biden would permanently ban new offshore oil and gas drilling across much of US coastal waters (over 600 million acres along the East Coast, West Coast, Gulf of Mexico and the Northern Bering Sea off Alaska). For example, Guardian journalist Oliver Milman wrote, “Joe Biden has banned offshore drilling across an immense area of coastal waters, weeks before Donald Trump takes office pledging to massively increase fossil fuel production. The US president’s ban encompasses the entire Atlantic coast and eastern Gulf of Mexico, as well as the Pacific coast off California, Oregon and Washington, and a section of the Bering Sea off Alaska. A White House statement said the declaration protected more than 253m hectares (625m acres) of waters. Trump said he would “unban it immediately” as soon as he re-enters the White House on 20 January, although it is unclear whether he will be able to do this easily. “As the climate crisis continues to threaten communities across the country and we are transitioning to a clean energy economy, now is the time to protect these coasts for our children and grandchildren,” Biden said in a statement. “In balancing the many uses and benefits of America’s ocean, it is clear to me that the relatively minimal fossil fuel potential in the areas I am withdrawing do not justify the environmental, public health, and economic risks that would come from new leasing and drilling,” he added. Scientists are clear that oil and gas production must be radically cut to avoid disastrous climate impacts. The ban does not have an end date and could be legally – and politically – tricky for Trump to overturn. Biden is taking the action under the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act of 1953, which gives the federal government authority over the exploitation of offshore resources. A total of eight presidents have withdrawn territory from drilling under the act, including Trump himself who barred oil and gas extraction off the coasts of Florida, Georgia and South Carolina. However, the law does not expressly provide for presidents to unilaterally reverse a drilling ban without going through Congress. Despite this, Trump vowed to undo Biden’s move, with the president-elect’s spokesperson, Karoline Leavitt, calling it “a disgraceful decision” and saying the incoming administration would “drill, baby, drill””.

Elsewhere, the methane leak from the Nord Stream sabotage – with connections made to climate change – emerged in January media coverage. For example, El País journalist Manuel Planelles wrote, “The sabotage of the Nord Stream pipeline caused the largest methane leak ever recorded: the equivalent of eight million cars in one year. A team of 70 scientists estimates the amount of CH₄ released into the atmosphere with the rupture of the gas pipeline at 465,000 tons, double what was previously believed. In September 2022, the Nord Stream gas pipeline network, which transported natural gas from Russia to Western Europe via the Baltic, was destroyed with explosives. This sabotage, which remains unsolved, although several media reports this summer pointed to an operation carried out by Ukraine following the Russian invasion, not only had consequences for European energy security. It also resulted in a huge leak of methane (CH₄), a powerful greenhouse gas that is in the crosshairs of the fight against climate change (…) Around 465,000 metric tons were emitted into the atmosphere, to which around fifty more were added that dissolved in the sea in one way or another”.

Image provided by the Government of Denmark about the gas leak in Nord Stream. Credit: Ministerio de Defensa Danés/DPA/Europa Press. |

Also in January in political and economic-themed news about climate change, several banking institutions exhibited what Timothy Snyder has called ‘anticipatory obedience’ as they have withdrawn from the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System. For example, Associated Press correspondent Christopher Rugaber reported, “The Federal Reserve said Friday that it is leaving an international grouping of central banks that focused on how regulation of the financial system could help combat climate change. The Fed’s membership has been criticized by Republicans in Congress. In a short statement, the Fed said it had “appreciated” working with the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System. But it added that the organization “has increasingly broadened in scope, covering a wider range of issues that are outside of the Board’s statutory mandate.” The move is another example of the central bank, which is intended to be independent of politics, taking steps that could insulate it from criticism from the incoming Trump administration. Earlier this month, Michael Barr, who headed up the Fed’s financial regulatory efforts and was fiercely opposed by large banks, said he would step down at the end of this month as vice chair for financial supervision. He remains on the Fed’s governing board. Stephen Miran, whom President-elect Donald Trump has named as a top White House economic adviser, co-authored a paper last year at the Manhattan Institute that criticized the Fed’s consideration of climate change in bank regulation as “mission creep.” The Fed said it would join the NGFS in December 2020, after President Joe Biden was elected, and was one of the last major central banks to do so. Over 140 central banks and financial regulatory agencies around the world are members”.

As January marched on, further actions of the incoming US Trump Administration and Republican majority House and Senate relating to climate policy generated significant news attention. US House Speaker Mike Johnson’s declaration to ‘restore America’s energy dominance’ fed news attention. For example, New York Times journalist Lisa Friedman reported, “Moments after his election as House speaker on Friday, Mike Johnson, Republican of Louisiana, wasted no time in highlighting energy as one of his top priorities. He said the Republican Congress would expand oil and gas drilling, end federal support for electric vehicles and promote the export of American gas. “We have to stop the attacks on liquefied natural gas, pass legislation to eliminate the Green New Deal,” he said in a floor speech after accepting the gavel. “We’re going to expedite new drilling permits, we’re going to save the jobs of our auto manufacturers, and we’re going to do that by ending the ridiculous E.V. mandates.” The Green New Deal to which Mr. Johnson referred was proposed legislation that Congress never passed but that Republicans have seized on as shorthand for policies designed to help the United States transition away from fossil fuels, the burning of which is dangerously heating the planet. Likewise, there is no mandate that requires Americans to buy electric vehicles. Instead, there are federal subsidies to encourage consumers to buy electric vehicles and new regulations designed to cut tailpipe pollution and get automakers to sell more E.V.s. Still, Mr. Johnson was clearly signaling that energy policy would be on the front burner. “It is our duty to restore America’s energy dominance and that’s what we’ll do,” he said. The United States is already the world’s biggest producer of crude oil as well as the biggest exporter of liquefied natural gas. House Republicans on Friday also made it easier for Congress to give away federal lands to state and local governments, a move that conservation groups warned could lead to Americans’ losing access to parks and other protected areas. The measure essentially renders public lands as having no monetary value by directing the federal government not to consider lost revenues when it transfers land to a state, tribe or municipality. While the same provision has been in effect when Republicans controlled Congress in the past, activists worry that under the Trump administration it will result in a sell-off of public lands. Mr. Trump has promised to expand oil and gas drilling and mining, a goal shared by Republicans who now control both the House and Senate. Environmental groups said they feared the measure approved Friday could open the door to new efforts to liquidate public lands. States often lack the resources to adequately maintain natural areas, they argue, and are more likely to sell formerly federal lands to mining and drilling companies or other private development”.

A coal-fired power plant in Kansas in 2021. Photo credit: Charlie Riedel/Associated Press. |

Then on his first day in office, Donald J. Trump again announced through Executive Order his administrations decision to withdraw from the 2015 United Nations (UN) Paris Climate Agreement. While Article 28 of the Paris Agreement states that the process requires one year before effective withdrawal, the Trump Administration definitively announced that by January 20, 2026 the US will join Yemen, Libya and Iran as the only parties to the UN to defect, leaving the global community of 196 cooperating parties working to address human contributions to climate change. For example, New York Times journalist Max Bearak reported, “President Trump on Monday signed an executive order to withdraw the United States from the Paris Agreement, the pact among almost all nations to fight climate change. By withdrawing, the United States will join Iran, Libya and Yemen as the only four countries not party to the agreement, under which nations work together to keep global warming below levels that could lead to environmental catastrophe. The move, one of several energy-related announcements in the hours following his inauguration, is yet another about-face in United States participation in global climate negotiations. During his first term Mr. Trump withdrew from the Paris accord, but then President Biden quickly rejoined in 2020 after winning the White House. Scientists, activists and Democratic officials assailed the move as one that would deepen the climate crisis and backfire on American workers. Coupled with Mr. Trump’s other energy measures on Monday, withdrawal from the pact signals his administration’s determination to double down on fossil-fuel extraction and production, and to move away from clean-energy technologies like electric vehicles and power-generating wind turbines”. Meanwhile, as an example of international media reaction Times journalist Oliver Wright wrote, “Sir Keir Starmer has refused to criticize Donald Trump’s plan to pull the United States out of the Paris climate change agreement as the prime minister attempts to avoid antagonizing the new American administration. The European Union led international criticism of the move, describing Trump’s decision as “truly unfortunate”. However, Downing Street refused to follow suit saying that the US was an “indispensable ally” and pointing out that Trump had been elected on a mandate to pull out of the agreement. Signed in 2015, the legally binding Paris Agreement requires countries to commit to progressively reduce their greenhouse gas emissions in a bid to limit global heating to below 2C. When he was first elected president in 2016, Trump pulled the US out of the agreement, leading to criticism by the then prime minister Theresa May. She warned that the move risked creating a “crisis of faith in multilateralism and global co-operation” that would “damage the interests of all our peoples”. When Joe Biden won the White in 2020, one of his first acts as president was to rejoin the agreement”. And on other world leaders including China’s reaction, Associated Press correspondents David Keyton and Sibi Arasu noted, “As expected, day two of the World Economic Forum at Davos, Switzerland witnessed strong responses to U.S. President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Paris climate agreement, with European leaders stating in no uncertain terms that they will hold fort and remain a part of the global climate pact. European Union chief Ursula von der Leyen said on Tuesday: “Europe will stay the course, and keep working with all nations that want to protect nature and stop global warming.” She insisted that the 27-nation bloc will stick to the landmark Paris climate accord. “The Paris Agreement continues to be the best hope for all humanity,” she said. The Paris accord is aimed at limiting long-term global warming to 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit (1.5 degrees Celsius) or, failing that, keeping temperatures at least well below 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius) above pre-industrial levels…In a session at Davos that looked at Europe’s transition to clean energy, Alexander De Croo, Belgium’s prime minister responded to Trump’s decision saying, “I mean, the world is full of uncertainty after yesterday even more, and maybe tomorrow there might be even more uncertainty. Let’s please, as Europeans within the European Union, not add to the uncertainty by creating ambiguity on our goals.” Business leaders at Davos chimed with the benefits of sticking to a global climate mandate. Jesper Brodin, chief executive officer of global furniture company, IKEA said: “For us, who have been on the bumpy train ride for a couple of years, we are discovering year by year how we actually not only can succeed to deliver to the Paris Agreement but actually how it benefits, business.” Climate scientists and activists from the Global South were more critical of the U.S.'s withdrawal from the climate pact. “Globally, Trump’s decision undermines the collective fight against climate change at a time when unity and urgency are more critical than ever. The most tragic consequences, however, will be felt in developing countries,” said New Delhi-based Harjeet Singh, of the Fossil Fuels Non Proliferation Treaty These vulnerable nations and communities, which have contributed the least to global emissions, will bear the brunt of intensifying floods, rising seas, and crippling droughts.” Speaking at Davos, Damilola Ogunbiyi, CEO and Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Sustainable Energy for All said, “We’re already collaborating at a scale where no one can stop, you know, not one country, not one leader making a decision. Because it’s just the right thing to do globally.” China also expressed concern over the U.S. move to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Guo Jiakun said: “Climate change is a common challenge facing mankind,” adding that “no country can be outside of it. No country can be immune to it””.

At the end of the month of January, New York Times journalist David Gelles reflected on the first two weeks of the US Trump Administration, writing, “Over the past four years during the Biden administration, the United States started spending ever-greater sums on efforts to blunt global warming and help communities adapt to a hotter world. Many analysts expected the total tab for this work to exceed $1 trillion over the next decade. But in a matter of days, President Trump has thrown much of that spending into question, though how much money is affected is unclear. Some funds are frozen. Some projects are paused. And while a portion of that money is already out the door, there is an acute sense of uncertainty among people doing climate-related work that relies on government funding and approvals. To take just one example of the chaos, consider the aid that the United States sends to foreign countries to deal with climate change. The United States Agency for International Development alone manages appropriations of roughly $40 billion annually, a fraction of which goes to climate-related projects. Raj Kumar, the chief executive officer of Devex, a media company that tracks foreign aid closely, said he had spent the past week on the phone with the leaders of organizations working on development projects around the world, and even he can’t make sense of this moment”. Moreover, New York Times correspondent Chris Flavelle noted, “President Trump’s energy agenda calls for drilling more oil and gas, something that could take years. But he took other actions this week that could more quickly affect the way the country prepares for and adapts to climate changes driven by the burning of fossil fuels. In 2021, President Biden ordered the Pentagon and Department of Homeland Security to study the security implications of climate change and to incorporate them into defense strategy and other national security plans. In response, the Pentagon, Homeland Security and the intelligence community detailed how food shortages could lead to social unrest, how countries may fight over dwindling water supplies and how people would flee climate shocks in places like Latin America, increasing migration to the United States. President Trump rescinded that order on Monday. That doesn’t prevent the Defense Department from considering climate change in its planning. But Pete Hegseth, Mr. Trump’s pick for defense secretary, has made comments that are dismissive of climate change, calling it an effort to establish government control”.

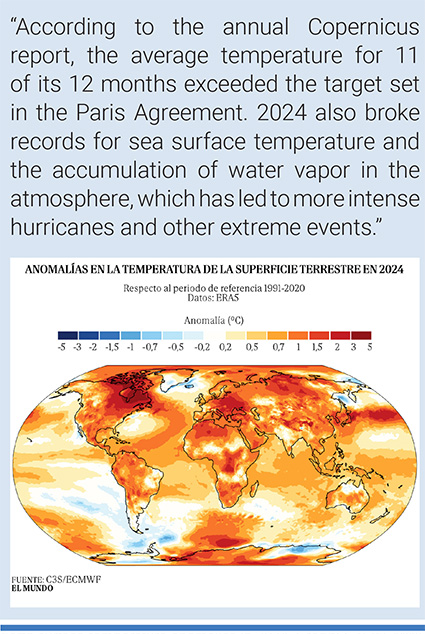

Earth surface temperature anomalies in 2024. Credit: C3S/ECMWF/El Mundo. |

Next, media portrayals in January also focused on ecological and meteorological themes in various stories. To start the month there was news of global temperature surpassing a 1.5oC (2.7oF) temperature threshold in the heels of the warmest year (2024) on planet Earth. For example, BBC correspondents Mark Poynting, Erwan Rivault and Becky Dale wrote, “The planet has moved a major step closer to warming more than 1.5oC, new data shows, despite world leaders vowing a decade ago they would try to avoid this. The European Copernicus climate service, one of the main global data providers, said on Friday that 2024 was the first calendar year to pass the symbolic threshold, as well as the world's hottest on record. This does not mean the international 1.5C target has been broken, because that refers to a long-term average over decades, but does bring us nearer to doing so as fossil fuel emissions continue to heat the atmosphere. Last week UN chief António Guterres described the recent run of temperature records as "climate breakdown". "We must exit this road to ruin - and we have no time to lose," he said in his New Year message, calling for countries to slash emissions of planet-warming gases in 2025”. Elsewhere, El Mundo journalist Teresa Guerrero wrote, “According to the annual Copernicus report, the average temperature for 11 of its 12 months exceeded the target set in the Paris Agreement. 2024 also broke records for sea surface temperature and the accumulation of water vapor in the atmosphere, which has led to more intense hurricanes and other extreme events. It has also been a year with numerous extreme weather events around the world, from severe storms and floods to heat waves, droughts and forest fires. In fact, both the annual climate report by Copernicus and those of other organizations such as NASA, NOAA, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) or the British Met Office - which will publish their analyses throughout this Friday - come the same week in which California suffers one of the worst fires in its history, fueled by very strong winds, and large areas of the USA have faced historic snowfalls.”

Also in January, winter weather with possible links made to climate change earned media attention. For example, BBC journalist Lucy Sheriff wrote, “Intense snowy wintry weather in the US has been fueled by activity of the polar vortex, slipping down to engulf large parts of the country. Early January's winter storm prompted seven states to declare states of emergency, with flights suspended, businesses shuttered and one area in New York recording 6.25ft (1.9m) of snowfall in just 24 hours. Another wave of Arctic air has kept temperatures lower than average through to the middle of January, and parts of the Midwest to the Appalachians and Atlantic Seaboard are expecting further wintry storms. This blast of cold weather is due to activity of the polar vortex… It is not known whether climate change will affect the polar vortex, says Amy Butler, an atmospheric scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and an expert on the polar vortex. There are several reasons why it is so hard to predict whether polar vortexes will strengthen or weaken in years to come”.

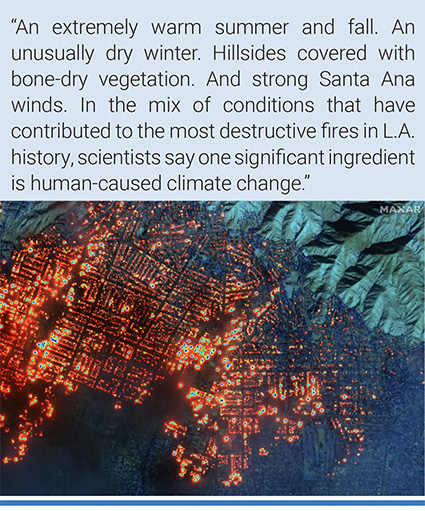

Satellite images collected by Maxar show the destruction of the Eaton Fire and Palisades Fire burning in Southern California. Credit: Maxar. |

But most prominent in January news connecting the dots between ecological and meteorological events and climate change was attention paid to the devastating and destructive fire that spread across Los Angeles, California. While many stories about the fires did not address climate change, many still did. For example, US National Public Radio journalist Lauren Sommer reported, “In early January, the stage was set for a wildfire disaster in Los Angeles. A long, hot summer had dried out the plants and vegetation, making it more flammable. Drought conditions dragged on, as winter rains had yet to arrive. Then came powerful Santa Ana winds, gusting above 80 miles per hour. The result was more than 16,000 homes and buildings were destroyed after the fast-moving Eaton and Palisades fires exploded. In those extreme conditions, firefighters had little hope of getting control of the blazes. New studies are finding the fingerprints of climate change in these wildfires, which made some of the extreme conditions worse. In particular, the hotter temperatures and a drier atmosphere can be linked to heat-trapping gases that largely come from burning fossil fuels, according to two different analyses from the University of California, Los Angeles, and World Weather Attribution, a collaboration of international scientists. Still, for other extreme conditions that led to Los Angeles' fires, like the strong Santa Ana winds and lack of rain, discerning the role of climate change is scientifically trickier. While there may be a connection to climate change, it's harder to recognize given the state's highly variable weather, which normally swings from wet to dry years. The powerful computer models scientists use to analyze climate impacts also struggle with very small geographic areas or complex processes, like wildfire behavior. Climate scientists are developing ways to pinpoint the role climate change is playing in wildfires. Still, the most significant human influence may be how the wildfires started since there were no lightning storms at the time that would have sparked the fires”. Meanwhile, Los Angeles Times reporter Ian James wrote, “An extremely warm summer and fall. An unusually dry winter. Hillsides covered with bone-dry vegetation. And strong Santa Ana winds. In the mix of conditions that have contributed to the most destructive fires in L.A. history, scientists say one significant ingredient is human-caused climate change. A group of UCLA climate scientists said in an analysis this week that if you break down the reasons behind the extreme dryness of vegetation in Southern California when the fires started, global warming likely contributed roughly one-fourth of the dryness, one of the factors that fueled the fires’ explosive spread. Extreme heat in the summer and fall desiccated shrubs and grasses on hillsides, they said, enabling those fuels to burn more intensely once ignited. The scientists said without the higher temperatures climate change is bringing, the fires still would have been extreme, but they would have been “somewhat smaller and less intense.” The conditions that made such catastrophic fires possible are like three switches that all happened to be flipped on at the same time, said Park Williams, a climate scientist who prepared the analysis with colleagues Alex Hall, Gavin Madakumbura and others in UCLA’s Climate and Wildfire Research Initiative”. And Washington Post correspondent Diana Leonard wrote, “The unusually strong Santa Ana windstorm made the event a “recipe for disaster” he said, especially given the high population downslope of where the ignitions occurred. “To have almost no precipitation at this point in the year is very unusual for us,” Alex Hall, a climate scientist at the University of California at Los Angeles, said in an interview. “Typically, we have our first rains in November … and it’s enough to quench the thirst of the plants that have been dormant for much of the summer.” The rain would typically shut off the ability of Santa Ana winds — which ramp up in October and can blow through the winter — to create very large wildfires”.

Next, several January 2025 stories drew on primarily scientific themes when reporting on climate change or global warming. For instance, while links were being explored about connections between the fires in Los Angeles and climate change, the World Weather Attribution team published a study that earned significant media attention. For example, Guardian correspondent Damien Carrington noted, “A triple whammy of climate impacts boosted the risk of the ferocious fires that recently ravaged Los Angeles, a scientific study has shown. Firstly, the hot, dry and windy conditions that drove the fires were made 35% more likely by the global heating caused by fossil fuel burning. Secondly, the low rainfall seen from October to December is now about 2.4 times more likely than in the preindustrial past, before the climate crisis. Rains during these months have historically brought an end to the wildfire season around LA. Thirdly, conditions of high fire risk have extended by more than three weeks in today’s heated climate, now reaching into January. This means fires have more chance of breaking out during the peak Santa Ana winds, which can blow small fires into deadly infernos”. Also, BBC reporter Matt McGrath wrote, “Climate change was a major factor behind the hot, dry weather that gave rise to the devastating LA fires, a scientific study has confirmed. It made those weather conditions about 35% more likely, according to World Weather Attribution - globally recognized for their studies linking extreme weather to climate change. The authors noted that the LA wildfire season is getting longer while the rains that normally put out the blazes have reduced. The scientists highlight that these wildfires are highly complex with multiple factors playing a role, but they are confident that a warming climate is making LA more prone to intense fire events”. And El País journalist María Mónica Monsalves wrote, “Climate change made the conditions that fueled California's wildfires 35% more likely. The World Weather Attribution group of scientists presented the results of their latest study. Seasons with fire-prone factors are now 23 days longer. Climate change is making everything more extreme, and the tragic wildfires that hit Southern California earlier this year are no exception. According to a study published by the World Weather Attribution (WWA) initiative — a group of scientists seeking to answer the question of climate change’s role in these types of events as quickly as possible — it states that global warming did increase the likelihood of the Palisades and Eaton fires, the two that ignited Los Angeles, in which at least 28 people died and more than 16,000 properties were lost. “They have been the most destructive in the history of Los Angeles and potentially the most costly in the history of the United States,” the organization says in a statement”.

Figure 4. Examples of newspaper front pages with climate change stories relating to the Los Angeles, California area fires – with connections made to climate change – in January 2025.

An Electrify America public charging station in Monterey Park, California: Photo credit: Frederic J. Brown/AFP/Getty Images. |

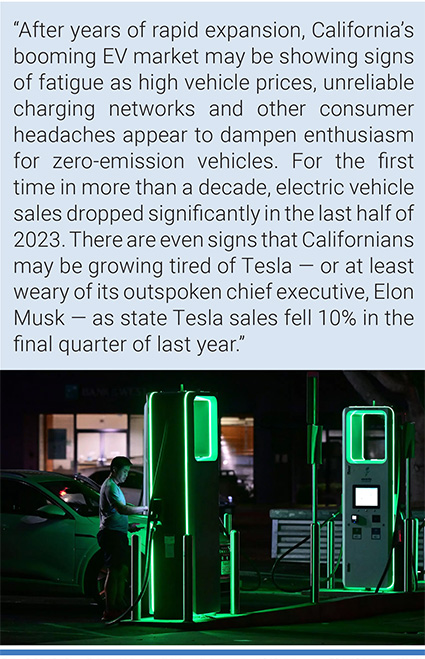

Last, cultural-themed stories relating to climate change or global warming also were evident in January, showing that climate change is not a single issue but a set of intersecting issues that thread through our lives and livelihoods, weaving through the many ways we work, play, recreate, play and rest in this world. To illustrate, while climate politics and policy dominated climate change news in January 2025, signs of a shifting electric vehicle (EV) market – with connections to avoiding climate change contributing emissions from gas-powered vehicles – were part of the January public discussion. For instance, Los Angeles Times reporter Russ Mitchell noted, “After years of rapid expansion, California’s booming EV market may be showing signs of fatigue as high vehicle prices, unreliable charging networks and other consumer headaches appear to dampen enthusiasm for zero-emission vehicles. For the first time in more than a decade, electric vehicle sales dropped significantly in the last half of 2023. There are even signs that Californians may be growing tired of Tesla — or at least weary of its outspoken chief executive, Elon Musk — as state Tesla sales fell 10% in the final quarter of last year”. Furthermore, New York Times journalist Lawrence Ulrich reported, “Many car buyers have come to rely on a $7,500 federal tax credit on electric vehicles to soften the blow of their high prices. But those credits could disappear after President-elect Donald J. Trump takes office, leading to an almost immediate drop in sales of the cars and trucks. Electric car sales could fall 27 percent if consumers lose the tax break, according to estimates published last week by three economics professors, Joseph Shapiro of the University of California, Berkeley, Felix Tintelnot of Duke University and Hunt Allcott of Stanford. Registrations of electric models are on track to hit 1.2 million this year, and estimates are that there would be about 317,000 fewer registered annually without the credit. Other countries that eliminated such subsidies have seen similar drops — in Germany, electric vehicle sales tumbled 27 percent in the first 10 months of the year, after the government last December abruptly canceled an incentive worth $4,900”.

In other culture-themed news, in January US billionaire Michael Bloomberg announced that his foundation was going to step in to fund the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in the absence of Trump Administration contributions. For example, Straits Times reported, “Mr Bloomberg’s intervention aims to ensure that the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) remains fully funded, despite the US halting its contributions. The US typically provides 22 per cent of the UNFCCC secretariat’s budget, with the body’s operating costs for 2024 to 2025 projected at €88.4 million (S$124.9 million). “From 2017 to 2020, during a period of federal inaction, cities, states, businesses and the public rose to the challenge to uphold our nation’s commitments – and now, we are ready to do it again,” Mr Bloomberg, who serves as the UN Special Envoy on Climate Ambition and Solutions, said in a statement. This marks the second time Mr Bloomberg has stepped in to fill the gap left by US federal disengagement. In 2017, following the Trump administration’s first withdrawal from the Paris accord, Mr Bloomberg pledged up to US$15 million to support the UNFCCC. He also launched America’s Pledge, an initiative to track and report US non-federal climate commitments, ensuring the world could monitor US progress as if it were still a fully committed party to the Paris Agreement. Mr Bloomberg reiterated his commitment to upholding US reporting obligations this time as well”.

Figure 5. Examples of newspaper front pages with climate change stories in January 2025.

- report prepared by Max Boykoff, Rogelio Fernández-Reyes, Ami Nacu-Schmidt, Jeremiah Osborne-Gowey and Olivia Pearman