Monthly Summaries

Issue 96, December 2024 | "Disappointing results this year, worrying many nations"

[DOI]

This holiday season, contribute to MeCCO’s ongoing work via this link to make a donation. |

Sunflowers appear wilted in a field amid a drought near the town of Becej, Serbia, in 2024. Photo credit: Darko Vojinovic/AP.

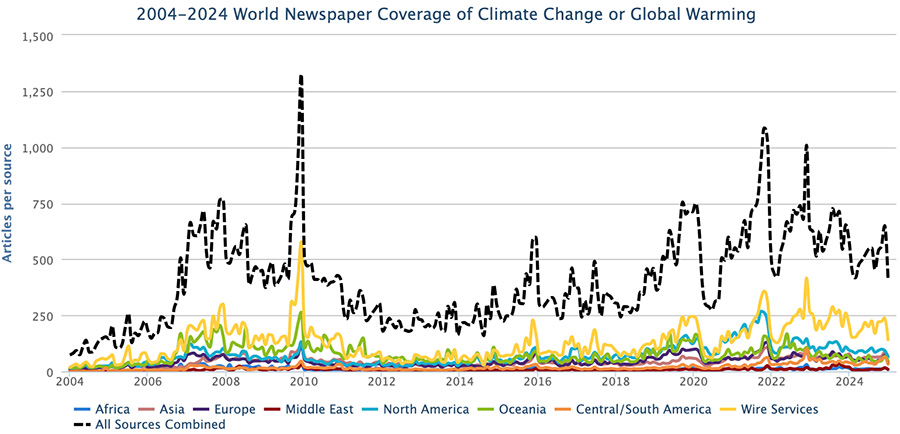

December media coverage of climate change or global warming in newspapers around the globe went down 38% from November 2024. Furthermore, coverage in December 2024 dropped 31% from December 2023. Figure 1 shows trends in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – across 21 years, from January 2004 through December 2024.

Figure 1. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in print sources in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through December 2024.

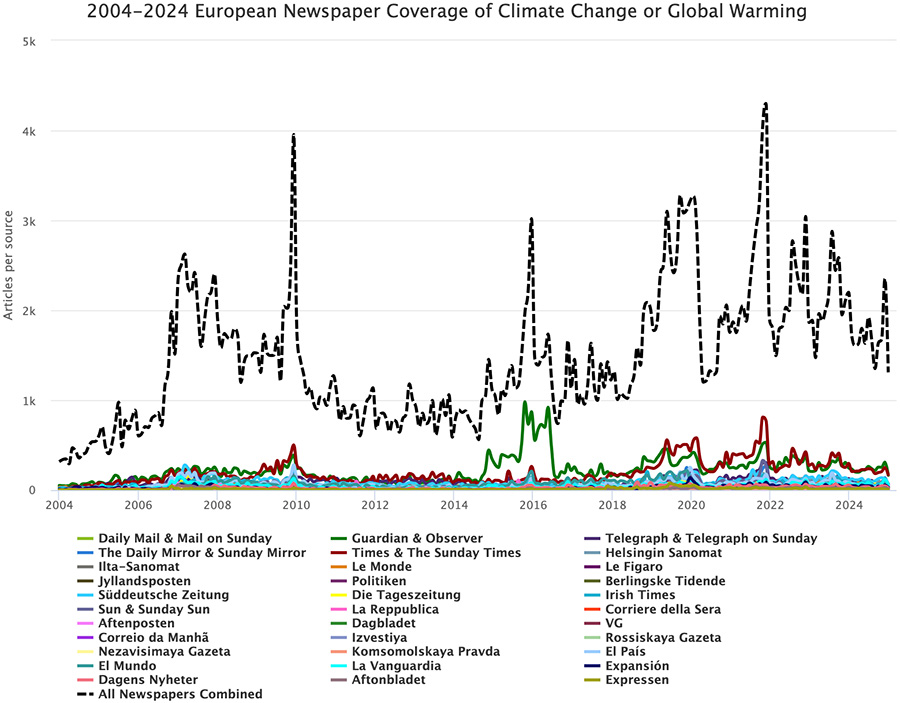

At the regional level, December 2024 coverage decreased in all regions compared to the previous month of November: Oceania diminished 28%, North America dropped 29%, Asia dipped 30%, the European Union (EU) went down 44% (see Figure 2), Africa decreased 44%, the Middle East dropped 45%, and Latin America plummeted 50%.

Figure 2. Coverage of climate change or global warming in 33 European newspapers across 12 countries from January 2004 through December 2024: Jyllandsposten (Denmark), Politiken (Denmark), Berlingske Tidende (Denmark), Daily Mail and Mail on Sunday (England), Guardian and Observer (England), Sun and Sunday Sun (England), Telegraph and Telegraph on Sunday (England), The Daily Mirror and Sunday Mirror (England), Times and The Sunday Times (England), Helsingin Sanomat (Finland), Ilta-Sanomat (Finland), Le Monde (France), Le Figaro (France), Süddeutsche Zeitung (Germany), Die Tageszeitung (Germany), Irish Times (Ireland), La Repubblica (Italy), Corriere della Sera (Italy), Aftenposten (Norway), Dagbladet (Norway), VG (Norway), Correio da Manhã (Portugal), Izvestiya (Russia), Rossiskaya Gazeta (Russia), Nezavisimaya Gazeta (Russia), and Komsomolskaya Pravda (Russia), El País (Spain), El Mundo (Spain), La Vanguardia (Spain), Expansión (Spain), Dagens Nyheter (Sweden), Aftonbladet (Sweden), and Expressen (Sweden).

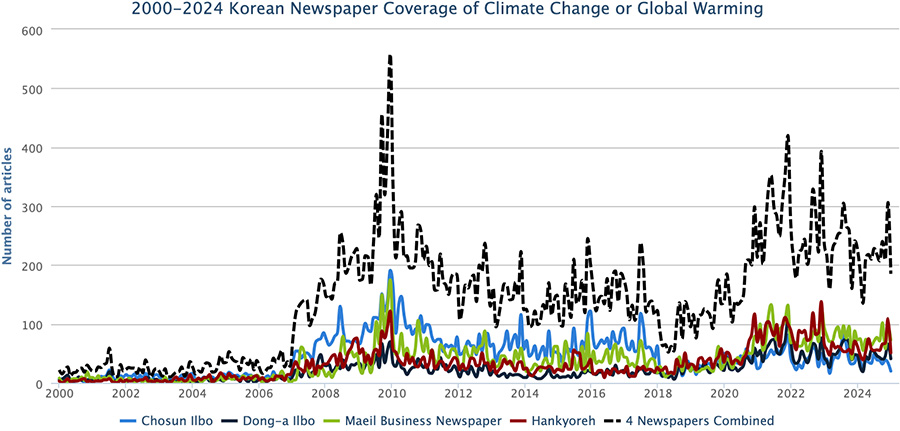

Among our country-level monitoring, for example Korean print coverage (see Figure 3) went down 39%. Attention paid to the failed self-coup as well as impeachment and consequent political instability combined with the air disaster in South Korea in December apparently drew news stories from domestic treatment of climate change and global warming or other issues.

Figure 3. Korean newspapers’ – Chosun Ilbo, Dong-a Ilbo, Maeil Business Newspaper, and Hankyoreh – coverage of climate change or global warming from January 2000 through December 2024.

A wildfire in California this year. Fires driven by severe droughts have affected the western US, Canada, the Amazon forest and particularly the Pantanal wetlands. Photo credit: David McNew/Getty Images. |

To start our analysis of themes of coverage, media portrayals in December drew on ecological and meteorological themes in various stories. In December, prominently the EU Copernicus Climate Change Service announce 2024 as the hottest year on record. This cohered with National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) assessments and generated considerable media attention. For example, Guardian environment editor Damien Carrington wrote, “This year is now almost certain to be the hottest year on record, data shows. It will also be the first to have an average temperature of more than 1.5C above preindustrial levels, marking a further escalation of the climate crisis. Data for November from the EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) found the average global surface temperature for the month was 1.62C above the level before the mass burning of fossil fuels drove up global heating. With data for 11 months of 2024 now available, scientists said the average for the year is expected to be 1.60C, exceeding the record set in 2023 of 1.48C. Samantha Burgess, the deputy director of C3S, said: “We can now confirm with virtual certainty that 2024 will be the warmest year on record and the first calendar year above 1.5C. This does not mean that the Paris agreement has been breached, but it does mean ambitious climate action is more urgent than ever.” The Paris climate agreement commits the 196 signatories to keeping global heating to below 1.5C in order to limit the impact of climate disasters. But this is measured over a decade or two, not a single year. Nonetheless, the likelihood of keeping below the 1.5C limit even over the longer term appears increasingly remote. The CO2 emissions heating the planet are expected to keep rising in 2024, despite a global pledge made in late 2023 to “transition away from fossil fuels”. Fossil fuel emissions must fall by 45% by 2030 to have a chance of limiting heating to 1.5C. The recent Cop29 climate summit failed to reach an agreement on how to push ahead on the transition away from coal, oil and gas. The C3S data showed that November 2024 was the 16th month in a 17-month period for which the average temperature exceeded 1.5C. The supercharging of extreme weather by the climate crisis is already clear, with heatwaves of previously impossible intensity and frequency now striking around the world, along with fiercer storms and worse floods. Particularly intense wildfires blazed in North and South America in 2024, the EU’s Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (Cams) reported last week. The fires, driven by severe droughts, affected the western US, Canada, the Amazon forest and particularly the Pantanal wetlands”. As another example elsewhere, Japan’s Yomiuri Shimbun reported, “This year will be the world’s warmest since records began, with extraordinarily high temperatures expected to persist into at least the first few months of 2025…The data from the EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) comes after U.N. climate talks yielded a $300 billion deal to tackle climate change, a package poorer countries blasted as insufficient to cover the soaring cost of climate-related disasters. C3S said data from January to November had confirmed 2024 is now certain to be the hottest year on record, and the first in which average global temperatures exceed 1.5 C above the 1850-1900 pre-industrial period. The previous hottest year on record was 2023. Extreme weather has swept around the world in 2024, with severe droughts hitting Italy and South America, fatal floods in Nepal, Sudan and Europe, heatwaves in Mexico, Mali and Saudi Arabia that killed thousands, and disastrous cyclones in the U.S. and the Philippines. Scientific studies have confirmed the fingerprints of human-caused climate change on all of these disasters. Last month ranked as the second-warmest November on record after November 2023”.

The Arctic tundra is warming up and that's causing long-frozen ground to melt as well as an increase in wildfires. Photo credit: Gerald Frost/Courtesy of NOAA. |

There were also several stories in the month of December that discussed regional anomalies in weather that were attributed to a changing climate. For instance, there were news accounts about warmth in Spain. For example, El País journalist Victoria Torres Benayas wrote, “This autumn has been a very warm season and for 14 long years there has not been an autumn with temperatures below normal in Spain. "The trend due to climate change is towards increasingly warmer autumns and many of them become an extension of summer," stressed this Thursday the spokesman for the Aemet, Rubén del Campo, during the presentation of the seasonal balance and the forecast for winter. "The last cold autumn was in 2010 and the rest, except for three normal ones, have all been either warm or very warm or extremely warm," Del Campo said in response to questions from this newspaper. In the heat ranking, the last autumn - in meteorology, this season runs from September 1 to November 30 - occupies the seventh place of the warmest autumns in the series and the sixth of the 21st century. A few days before the end of 2024, this year is the third warmest since records began in Spain, although, worldwide, a new record will be broken. warmer than usual, according to the European Union's Copernicus space observation system. And winter is also likely to be warmer than usual”.

In mid-December, in the Indian Ocean cyclone Chido imparted devastation on island communities. Its intense strength was attributed in part to climate change, and this then prompted several news accounts. For example, Associated Press correspondent Taiwo Adebayo wrote, “The Indian Ocean archipelago of Mayotte is reeling from Cyclone Chido, the most intense storm to hit the French territory in 90 years. At least 22 people have been killed since Chido made landfall on Saturday, as high winds swept away entire neighborhoods, damaged major infrastructure and uprooted trees. And while Africa’s southeast coast is no stranger to devastating cyclones, climate scientists have warned in recent years that storms in the area are getting more intense and more frequent as a result of human-caused climate change”. Meanwhile, journalists from Le Monde reported, “France will observe a day of national mourning, on Monday, December 23, for the French overseas department of Mayotte, President Emmanuel Macron said, after the department's Indian Ocean archipelago was devastated by a cyclone, with lacking water and food, and fear of looting gripping residents…A preliminary toll from France's interior ministry shows that 31 people have been confirmed killed, 45 seriously hurt, and more than 1,370 suffering lighter injuries, but officials say that, realistically, a final death toll of hundreds or even thousands is likely. "The tragedy of Mayotte is probably the worst natural disaster in the past several centuries of French history," Prime Minister Francois Bayrou said. In response to widespread shortages, the government issued a decree freezing the prices of consumer goods in the archipelago at their pre-cyclone levels. Cyclone Chido, which hit Mayotte on Saturday, was the latest in a string of storms worldwide fueled by climate change, according to meteorologists”.

Scientists propose reducing long-distance flights to curb the climate impact of tourism. Photo credit: Marta Pérez/EFE. |

In December, several stories also drew on primarily scientific themes when reporting on climate change or global warming. For instance, early in the month at the annual American Geophysical Union meeting, NOAA released its 18th annual 'Arctic Report Card' which earned media attention around the world as it has done in previous years. For example, US National Public Radio journalist Barbara Moran reported, “Arctic tundra, which has stored carbon for thousands of years, has now become a source of planet-warming pollution. As wildfires increase and hotter temperatures melt long-frozen ground, the region is releasing greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The finding was reported in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's annual Arctic Report Card, released Tuesday. The new research, led by scientists from the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Falmouth, Massachusetts, signals a dramatic shift in this Arctic ecosystem, which could have widespread implications for the global climate”. Elsewhere, The Straits Times noted, “The Arctic tundra is undergoing a dramatic transformation, driven by frequent wildfires that are turning it into a net source of carbon dioxide emissions after millennia of acting as a carbon sink, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) said on Dec 10. This drastic shift is detailed in NOAA’s 2024 Arctic Report Card, which revealed that annual surface air temperatures in the Arctic in 2024 were the second-warmest on record since 1900. “Our observations now show that the Arctic tundra, which is experiencing warming and increased wildfire, is now emitting more carbon than it stores, which will worsen climate change impacts,” said NOAA administrator Rick Spinrad. Climate warming has dual effects on the Arctic. While it stimulates plant productivity and growth, removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, it also leads to increased surface air temperatures that cause permafrost to thaw. When permafrost thaws, carbon trapped in the frozen soil is decomposed by microbes and released into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide and methane – two potent greenhouse gases”. As a third example, The Jerusalem Post reported, “The Arctic tundra is now emitting more carbon dioxide than it absorbs, according to the latest Arctic Report Card released by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The annual assessment reveals that warming temperatures and increased wildfires have shifted the Arctic from a carbon sink to a net source of greenhouse gas emissions. "Our observations now show that the Arctic tundra, which is experiencing warming and increased wildfire activity, now emits more carbon than it stores, which will worsen the impacts of climate change," NOAA Administrator Rick Spinrad stated. The report highlights that the period from October 2023 to September 2024 was the second-warmest for the Arctic region since 1900, emphasizing numerous changes affecting both ecosystems and human communities. The thawing permafrost is a significant factor in this shift. When permafrost thaws, carbon that has been stored in the frozen soil is decomposed by microbes, leading to the release of carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere. The melting permafrost also activates microbes in the soil, leading to the decomposition of trapped carbon into greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide and methane”.

Aerial view of a coal-fired power plant near Ohio. Photo credit: Shutterstock. |

Also, in December there was attention paid to an article published in the journal Nature Communication concluded that CO2 emissions from tourism were growing twice as fast as those from the rest of the economy. For example, La Vanguardia journalist Rosa M. Tristán noted, “Yen Sun and her colleagues have already discovered, using data from 175 countries, that tourists’ emissions have increased by 3.5% each year between 2009 and 2020. Only 20 countries are responsible for three-quarters of the tourist carbon footprint. Overall, the 5.4 gigatons of CO2 generated annually by travel are equivalent to everything emitted by Latin America and the Caribbean in that period”.

As a third illustration along scientific-themed climate change media portrayals, a new International Energy Agency report found that global coal demand is set to rise to a new record this year and remain steady through 2027 while China, India, and countries in Southeast Asia are projected to account for 75% of global coal demand in 2024. For example, CBS News reported, “World coal use is set to reach an all-time high in 2024, the International Energy Agency said Wednesday, in a year all but certain to be the hottest in recorded history. Despite calls to halt humanity's burning of the filthiest fossil fuel driving climate change, the energy watchdog expects global demand for coal to hit record highs for the third year in a row. Scientists have warned that planet-warming greenhouse gases will have to be drastically slashed to limit global heating to avoid catastrophic impacts on the Earth and humanity…Published on Wednesday, the IEA's "Coal 2024" report does, however, predict the world will hit peak coal use in 2027 after topping 8.77 billion tons this year. But that would be dependent on China, which for the past quarter-century has consumed 30 percent more coal than the rest of the world's countries combined, the IEA said. China's demand for electricity was the most significant driving force behind the increase, with more than a third of coal burnt worldwide carbonized in that country's power plants. Though Beijing has sought to diversify its electricity sources, including a massive expansion of solar and wind power, the IEA said China's coal demand in 2024 will still hit 4.9 billion tones — itself another record. Increasing coal demand in China, as well as in emerging economies such as India and Indonesia, made up for a continued decline in advanced economies. However that decline has slowed in the European Union and the United States. Coal use there is set to decline by 12 and five percent respectively, compared with 23 and 17 percent in 2023. With the imminent return to the White House of Donald Trump — who has repeatedly called climate change a "hoax" — many scientists fear that a second Trump presidency would water down the climate commitments of the world's largest economy. Coal mining also hit unprecedented levels by topping nine billion tons in output for the first time, the IEA said, with top producers China, India and Indonesia all posting new production records. The energy watchdog warned that the explosion in power-hungry data centers powering the emergence of artificial intelligence was likewise likely to drive up demand for power generation, with that trend underpinning electricity demand in coal-guzzling China. The 2024 report reverses the IEA's prediction last year that coal use would begin declining after peaking in 2023. At the annual U.N. climate change forum in Dubai last year, nations vowed to transition away from fossil fuels”.

Youth plaintiffs in the Held v. Montana climate case leave the Montana Supreme Court. Photo credit: Thom Bridge/Independent Record/AP. |

A final brief science-themed example in December is a Nature Communications study that found the Arctic’s first ice-free day is likely to come before 2030 earned media attention. For example, Indian Express journalist Alind Chauhan reported, “the Arctic Ocean may see its first ice-free day — when its waters have less than one million square kilometres of sea ice — by 2030, or sooner than previously expected, according to a new study. The scenario is unlikely to happen but it is possible, and its plausibility is increasing as humans continue to emit heat-trapping greenhouse gases (GHGs) at unprecedented levels, the analysis said”.

Next, cultural-themed stories relating to climate change or global warming also cropped up in December, as it has done in previous months and years. To illustration, in the US a Montana Supreme Court decision about a constitutional right to a clean environment (including mentions of climate change) in favor of youth climate activists generated media attention. For example, Associated Press correspondent Amy Beth Hansen reported, “Montana’s Supreme Court on Wednesday upheld a landmark climate ruling that said the state was violating residents’ constitutional right to a clean environment by permitting oil, gas and coal projects without regard for global warming. The justices, in a 6-1 ruling, rejected the state’s argument that greenhouse gases released from Montana fossil fuel projects are minuscule on a global scale and reducing them would have no effect on climate change, likening it to asking: “If everyone else jumped off a bridge, would you do it too?” The plaintiffs can enforce their environmental rights “without requiring everyone else to stop jumping off bridges or adding fuel to the fire,” Chief Justice Mike McGrath wrote for the majority. “Otherwise the right to a clean and healthful environment is meaningless.” Only a few other states, including Hawaii, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and New York, have similar environmental protections enshrined in their constitutions. The lawsuit filed in 2020 by 16 Montanans —who are now ages 7 to 23 — was considered a breakthrough in attempts by young environmentalists and their attorneys to use the courts to leverage action on climate change”. Meanwhile, Washington Post journalist Anna Phillips wrote, “Montana’s permitting of oil, gas and coal projects without consideration for climate change violates residents’ constitutional right to a clean environment, the state’s Supreme Court ruled Wednesday, upholding a landmark ruling in a case brought by youth activists. The 6-1 ruling is a major, and rare, victory for climate activists, who have tried to use the courts to force action on government and corporate policies and activities they say are harming the planet. In their decision, the Montana justices affirmed an August 2023 ruling by a state judge, who found in favor of young people alleging the state violated their right to a “clean and healthful environment” by promoting the use of fossil fuels. Melissa Hornbein, a senior attorney with the Western Environmental Law Center, which served as co-counsel for the plaintiffs along with Our Children’s Trust, said the decision would force Montana state agencies to assess the greenhouse gas emissions and climate impacts of all future fossil fuel projects when deciding whether to approve or renew them”.

Photo credit: Getty Images. |

Finally, many enduring political and economic-themed media stories about climate change or global warming dominated various outlets in December. For example, UK climate policy action plans – and their execution to date – earned attention. For example, BBC journalist Esme Stollard reported, “The government has unveiled plans to give ministers the final say on approving large onshore wind farms rather than leaving decisions to local councils, where opposition has often been fierce. The plan is among proposals announced by Energy Secretary Ed Miliband on Friday as part of what the government is calling an "ambitious" action plan for reaching 95% clean energy in the UK by 2030. Miliband also wants to give powers to the energy regulator to prioritise projects in the queue waiting to link up with the National Grid… Onshore wind is one of the cheapest forms of clean energy. But there has been a 94% decline in projects in England since 2015 when the previous Conservative government tightened planning regulations for wind farms - following pushback from local communities over potential environmental damage. Subsequently, only a small number of local objections would be enough to effectively block new projects. Following Labour's general election victory, planning rules for onshore wind were eased in September 2024. But renewable energy groups said they did not go far enough. The public will still be consulted on new wind farms, but the secretary of state will be empowered to take any final decision -based on national priorities such as tackling climate change. Mr Miliband told the BBC's Today programme on Friday: "There are difficult tradeoffs here and unless we change the way we do things we are going to be left exposed as a country. "In the end it will be a national decision." The government maintains any project will need to have "direct community benefits" and proposes to establish a recovery fund to invest in nature projects as compensation for any environmental damage”.

The Naughton coal-fired power plant in Kemmerer, Wyoming. Photo credit: Kim Raff/New York Times. |

Similarly, US climate policy action plans generated news in December. This was sparked by the outgoing Biden Administration’s announcement to strengthen the old US goal to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 50% to 52% (compared to 2005 levels) by 2030 to a new goal to cut GHG emissions across the economy by 61% to 66% by 2035 while curbing methane by 35%, and reaching ‘net zero’ GHG emissions by 2050. For example, New York Times journalists Brad Plumer and Lisa Friedman reported, “President Biden on Thursday announced an aggressive new climate goal for the United States, saying that the country should seek to slash its greenhouse gas emissions by at least 61 percent below 2005 levels by 2035. The target is not binding and will almost certainly be disregarded by President-elect Donald J. Trump, who has called global warming a “scam.” But Biden administration officials said they hoped it would encourage state and local governments to continue to cut the emissions that are rapidly heating the planet, even if the federal government pulls back. The announcement caps four years of climate policies from a president who has sought to make global warming a signature focus of his administration. In a video address from the White House, Mr. Biden said his efforts, including pumping billions of dollars into clean energy technologies and regulating pollution from power plants and automobiles, amounted to “the boldest climate agenda in American history.” Mr. Biden said he expected progress in tackling climate change to continue after he had left office. “American industry will keep inventing and keep investing,” he said. “State, local, and tribal governments will keep stepping up. And together, we will turn this existential threat into a once-in-a-generation opportunity to transform our nation for generations to come.” The new pledge of cutting emissions 61 to 66 percent below 2005 levels by 2035 is a significant update of commitments that the United States had already made. In 2021, Mr. Biden promised that the country would cut its heat-trapping emissions at least 50 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. Scientists have said that global emissions must drop by roughly half this decade to keep global warming at relatively low levels. But while U.S. emissions have been trending downward, the country is not currently on pace to meet even the earlier goal. Last year, emissions were about 17 percent below 2005 levels, largely because electric utilities have retired many of their coal plants in favor of cheaper and cleaner gas, wind and solar power. But this year, emissions are expected to stay roughly flat, in part because rising electricity demand has led power companies to burn record amounts of gas, offsetting growth in renewable energy. Under the 2015 Paris climate agreement, every country agreed to submit a plan for curbing its greenhouse gas emissions, with the details left up to individual governments. Those pledges then get updated every five years. According to the Paris pact, countries are expected to issue a new round of plans before the next United Nations climate summit, scheduled for November in Belém, Brazil”.

Vanuatu Prime Minister Charlot Salwai Tabimasmas addresses the 79th session of the United Nations General Assembly. Photo: Richard Drew/AP. |

At the international level, interlinked United Nations (UN) desertification talks ended without an agreement. This generated news attention. For example, Associated Press reporter Sibi Arasu noted, “Despite two weeks of U.N.-sponsored talks in Saudi Arabia’s Riyadh, the participating 197 nations failed to agree early Saturday on a plan to deal with global droughts, made longer and more severe by a warming climate. The biennial talks, known as COP 16 and organized by a UN body that deals with combating desertification and droughts, attempted to create strong global mandates to legally bind and require nations to fund early warning systems and build resilient infrastructure in poorer countries, particularly Africa, which is worst affected by the changes. The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification released a report earlier this week warning that if global warming trends continue, nearly five billion people — including in most of Europe, parts of the western U.S., Brazil, eastern Asia and central Africa — will be affected by the drying of Earth’s lands by the end of the century, up from a quarter of the world’s population today. The report also said farming was particularly at risk, which can lead to food insecurity for communities worldwide. This is the fourth time UN talks aimed at getting countries to agree to make more headway on tackling biodiversity loss, climate change and plastic pollution have either failed to reach a consensus or delivered disappointing results this year, worrying many nations, particularly the most vulnerable”.

Then at the global level, climate policy decisions at the World Court generated news coverage in December. For example, Associated Press correspondent Molly Quell reported, “The top United Nations court will take up the largest case in its history on Monday, when it opens two weeks of hearings into what countries worldwide are legally required to do to combat climate change and help vulnerable nations fight its devastating impact. After years of lobbying by island nations who fear they could simply disappear under rising sea waters, the U.N. General Assembly asked the International Court of Justice last year for an opinion on “the obligations of States in respect of climate change.” “We want the court to confirm that the conduct that has wrecked the climate is unlawful,” Margaretha Wewerinke-Singh, who is leading the legal team for the Pacific island nation of Vanuatu, told The Associated Press. In the decade up to 2023, sea levels have risen by a global average of around 4.3 centimeters (1.7 inches), with parts of the Pacific rising higher still. The world has also warmed 1.3 degrees Celsius (2.3 Fahrenheit) since pre-industrial times because of the burning of fossil fuels. Vanuatu is one of a group of small states pushing for international legal intervention in the climate crisis”. Elsewhere, reporting in The Hindu noted, “France on Thursday urged the United Nations top court to "clarify" international law relating to the fight against climate change, saying judges had a "unique opportunity" to provide a clear legal framework. The International Court of Justice is holding historic hearings to craft a so-called "advisory opinion" on states' responsibilities to fight climate change and the consequences for those damaging the environment”. As a final example, El Mundo journalist Carlos Fresneda wrote, “The International Criminal Court heard testimony from 98 countries and a dozen organizations over two weeks. The high court will issue an "advisory opinion" on the responsibility of developed countries in 2025 that is expected to serve as the basis for future international legal disputes. "Climate change is not a distant threat, but a real and present danger that is affecting our lives, and is putting the existence of our own countries at risk," said Vishal Prasad, director of the group Pacific Islands Students Fighting Climate Change (PISFCC), which promoted the unprecedented initiative before the ICC”.

And many news accounts – from opinion pieces to straight news reporting – swirled with speculation about the politics of climate change to come in 2025. For example, Hindustan Times columnist Gopalkrishna Gandhi commented, “The year 2024 scorched and scalded but just about let the planet survive. Let us hope that the new year, despite portents of war and worsening of the climate crisis, proves different. Let us accept it. The sun sank last evening, disappointed. Disappointed in us, earthlings. In the way we are treating the earth and each other. Hoping against hope about the future of Planet Earth…”

Figure 4. Examples of newspaper front pages with climate change stories in December 2024.

- report prepared by Max Boykoff, Rogelio Fernández-Reyes, Lucy McAllister, Ami Nacu-Schmidt, Jeremiah Osborne-Gowey and Olivia Pearman