Monthly Summaries

Issue 109, January 2026 | "We hope for the best but we prepare for the worst”

[PDF]

Country Fire Authority firefighters douse a home amid the bushfire in Longwood, Victoria. Photo: Michael Currie/Reuters.

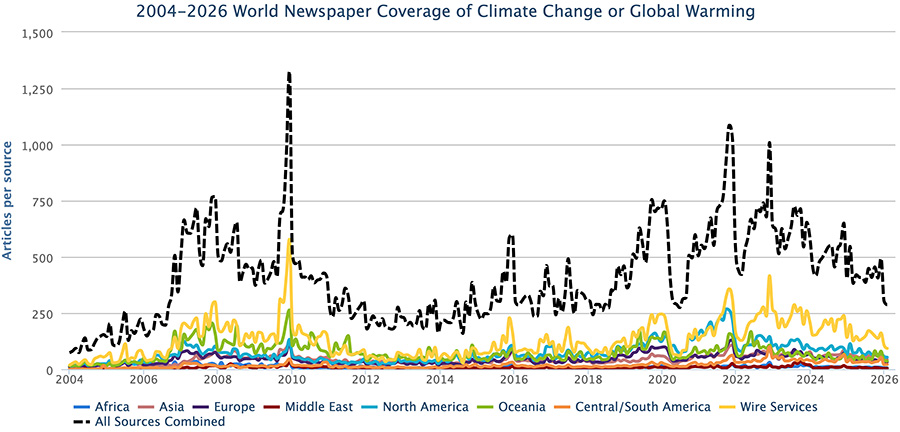

January media coverage of climate change or global warming in newspapers around the globe increased less than 1% from December 2025. However, coverage in January 2026 was markedly down 42% from January 2025. In January, international wire service coverage dropped 13% from the month earlier (December) and 53% from the previous year (January 2025). Figure 1 shows trends in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – across 22 years, from January 2004 through January 2026.

Figure 1. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in print sources in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through January 2026.

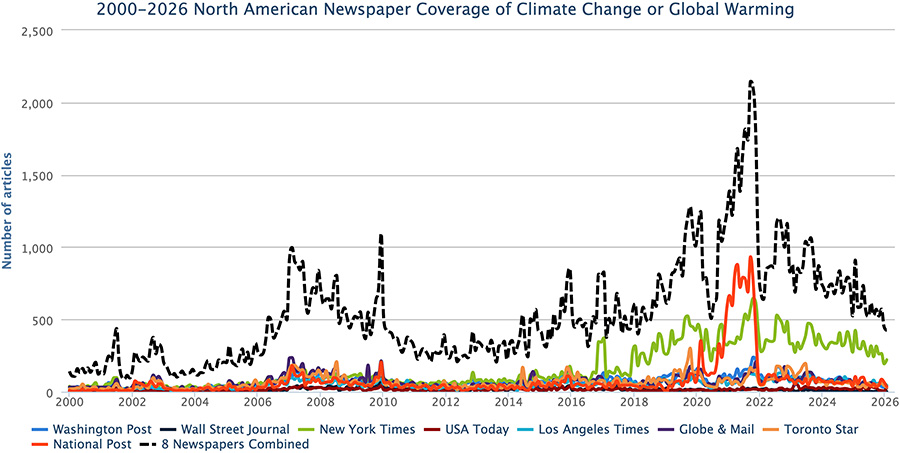

At the regional level, January 2026 coverage went down in Asia (-2%), Oceania (-5%), Africa (-5%) and North America (-5%) (see Figure 2), while increasing in the Middle East (+13%) and in the European Union (EU) (+13%) as well as in Latin America (+5%). Comparing January 2026 to January 2025 levels of coverage, numbers dramatically lower in all regions: North America (-5%), Africa (-28%), Asia (-36%), Oceania (-37%), the EU (-37%), Latin America (-51%), and the Middle East (-55%).

Figure 2. Coverage of climate change or global warming in North America from January 2000 through January 2026: Washington Post (US), Wall Street Journal (US), New York Times (US), USA Today (US), Los Angeles Times (US), Globe & Mail (Canada), Toronto Star (Canada), National Post (Canada).

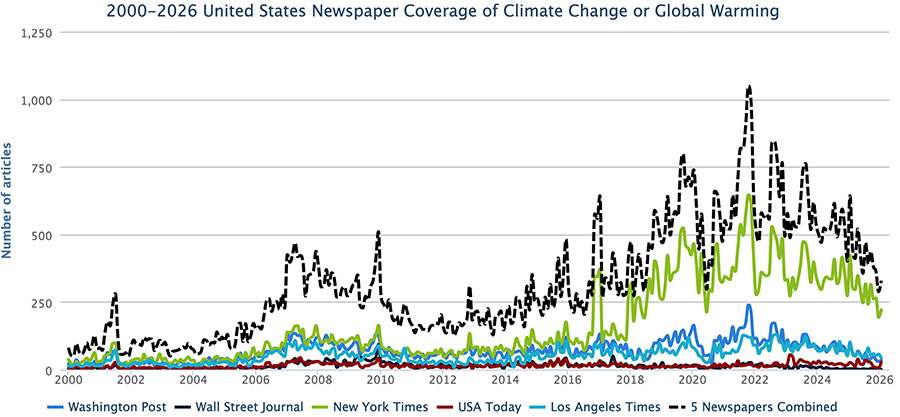

Among our country-level monitoring, in January US print coverage (see Figure 3) went up 14% from December 2025 levels of coverage. At the same time, US television coverage increased 33% in January, compared to low levels of December 2025 coverage.

Figure 3. US newspapers’ – Los Angeles Times, New York Times, USA Today, Wall Street Journal, and Washington Post – coverage of climate change or global warming from January 2000 through January 2026.

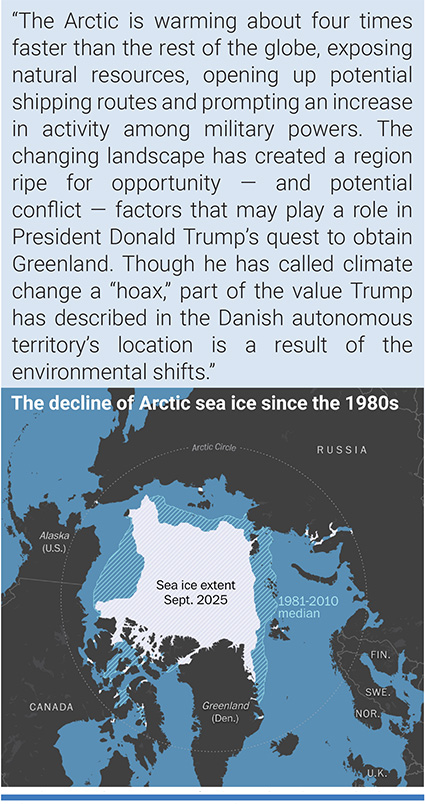

Map shows median ice extent for September, the month when ice cover is smallest. Source: Sea ice extent data via National Snow and Ice Data Center. |

To start our analysis of themes of coverage, political and economic-themed media stories about climate change or global warming fought for attention in various outlets in January. To begin, the US Trump Administration involvement in Venezuela prompted stories about connections to oil and climate change. For example, CNN journalist Laura Paddison asked, “What happens to the planet if Trump gets his hands on all of Venezuela’s oil?”. Meanwhile, New York Times correspondent David Gelles wrote, “Despite the Trump administration’s claims that it was targeting Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro over the flow of illegal drugs into the United States, the administration is now fixated on a very different Venezuelan export: oil. In the days since the extraordinary capture of Maduro in Caracas, which appeared to violate the United Nations Charter, President Trump and his allies have repeatedly talked up their plans to revive the Venezuelan oil industry”.

Early in the month, threats by the US Trump Administration to take over Greenland also generated many climate change related stories that spanned politics, economics, science and ecology/meteorology. For example, Washington Post correspondents Ruby Mellen and John Muyskens noted, “The Arctic is warming about four times faster than the rest of the globe, exposing natural resources, opening up potential shipping routes and prompting an increase in activity among military powers. The changing landscape has created a region ripe for opportunity — and potential conflict — factors that may play a role in President Donald Trump’s quest to obtain Greenland. Though he has called climate change a “hoax,” part of the value Trump has described in the Danish autonomous territory’s location is a result of the environmental shifts. “It’s partly the melting of sea ice making it more attractive for the economic development that he’d pursue in Greenland,” said Sherri Goodman, a distinguished fellow at the Atlantic Council and the former deputy undersecretary of defense for environmental security. Trump has said he wants the territory because of its strategic location and untapped natural resources, including diamonds, lithium and copper. The president announced tariffs Saturday on countries that have sent troops to Greenland in recent days. Talks last week between U.S. officials and the foreign ministers of Greenland and Denmark ended in “fundamental disagreement,” according to Denmark’s top diplomat, Lars Lokke Rasmussen. The prospect of the United States using military force against the NATO ally, as Trump has floated, could end the decades-old defense pact. His bid for the territory is one of the most concrete examples of how climate change is influencing geopolitics. As the northernmost parts of our planet continue to warm, the effects could change the ways the international community operates”.

Wind turbines in the city of Qingtongxia, in northern China. Photo: CFOTO/Future Publishing via Getty Images. |

Elsewhere, in the EU there were many news stories about how wind and solar power are growing in the world's major economies, while fossil fuel consumption is stagnating. For example, El País journalists Manuel Planelles and Ignacio Fariza noted, “In his rambling speech on Wednesday at the Davos Forum in Switzerland, Trump once again lashed out at renewable energy, the European Union, and the Green Deal, which aims to transform the energy and transportation systems to break the dependence on fossil fuels, the main cause of climate change. Trump, like the European and Spanish far right, spearheaded by Vox, dismissed the pact, calling it a "new green scam." But the truth is that, despite the attacks, renewable energy continued to grow in 2025, setting records while fossil fuel consumption for electricity generation stagnated…Renewables make economic sense, especially for European consumers. The deployment of renewables between 2019, when the European Green Deal was launched, and 2024 allowed the EU27 to save €59 billion in reductions in coal and gas imports alone, according to a report from the analyst group Ember…In 2025, solar and wind power generated more electricity in the EU than fossil fuels for the first time, another Ember report indicates.” Meanwhile, CNN journalists Andrew Freedman, Ella Nilsen and Samantha Waldenberg reported, “The Trump administration is pulling the United States out of the bedrock treaty that underpins international cooperation on climate change, along with dozens of other global bodies, according to a memorandum released by the White House Wednesday evening and an accompanying social media post. Such an action, if successful, would leave the US out of international climate change talks and could raise tensions with US allies for whom climate action is a priority. The agreement in question is the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, or UNFCCC, which the US joined and Congress ratified in 1992, when George H.W. Bush was in the White House. The agreement does not require the US to cut fossil fuels or pollution, but rather sets a goal of stabilizing the amount of climate pollution in the atmosphere at a level that would “prevent dangerous anthropogenic (human-caused) interference with the climate system.” It also set up a process for negotiations between countries that have come to be known as the annual UN climate summits. It was under the UNFCCC’s auspices that the Kyoto Protocol was negotiated in 1995, and the Paris Agreement in 2015 — two monumental moments of global cooperation and progress toward limiting harmful climate pollution. In addition, the agreement requires the submission of an annual national climate pollution inventory, which the Trump administration notably skipped this year. The exit from the climate treaty, and a slew of other international agencies, is another step back from the US on international cooperation”.

Furthermore, Washington Post correspondent Adam Taylor wrote, “The Trump administration announced Wednesday that it will withdraw the United States from dozens of international organizations and bodies associated with the United Nations as Washington retrenches from global cooperation on everything from climate change to cotton. In total, according to the White House, the United States will withdraw from 66 organizations or bodies. Of that number, 31 are entities associated with the United Nations. The White House said in a statement the U.S. will withdraw from the bodies and halt any funding because they “operate contrary to U.S. national interests, security, economic prosperity, or sovereignty”.”

Photo: Luke MacGregor/Reuters. |

Economics were also prevalent in many related January 2026 news stories. For example, Wall Street Journal correspondents Adam Whittaker and Matthew Dalton wrote, “BP said it would write down the value of its gas and low-carbon energy division by up to $5 billion, the legacy of an ill-timed move into renewables that left it the least profitable of the major oil companies. The London-based company is now in the early stages of a turnaround aimed at bringing the business back to its roots: drilling for oil and gas. BP has reined in investments in operations geared toward the energy transition, walked away from some renewable projects and abandoned plans to sharply reduce its oil and gas production”.

Next, media portrayals in January also focused on ecological and meteorological themes in various stories. To start the month there was news of Argentinian and Australian heat waves and climate change-related fire risks generated media attention. For example, Guardian reporter Petra Stock wrote, “A heatwave engulfing much of Australia pushed Melbourne’s mercury past 42C, as authorities urged Victorians to stay indoors on Friday. The extreme heat is forecast to descend on Sydney on Saturday. Anthony Albanese met officials in Canberra for a briefing on the extreme conditions and said these were “difficult times” for the country. The prime minister urged people to follow advice from officials, when instructed to evacuate properties in the path of a bushfire or advised not to risk driving in flood waters. “We hope for the best but we prepare for the worst,” he said. Melbourne’s maximum temperature was forecast to reach 43C on Friday, and up to 45C in some suburbs. The city was 42.9C at 3:40pm, with 44C recorded in suburbs including Laverton and Viewbank. Catastrophic and extreme fire danger ratings were in place throughout Victoria, with the entire state under a total fire ban. The central district, which includes Melbourne and Geelong, was approaching catastrophic with a fire danger rating of 99 (100 or more is considered catastrophic). Fires were expected to be “unpredictable, uncontrollable and fast-moving”, Victoria’s emergency management commissioner, Tim Wiebusch, said as the extreme heat combined with damaging winds and the risk of dry lightning. Extreme conditions extended across much of South Australia as well as the New South Wales Riverina. Heatwave warnings remained in place for all states and territories except Queensland”.

Snow piles up on the ground near a picture Donald Trump outside a home in West Des Moines, Iowa. Photo: Scott Morgan/Reuters. |

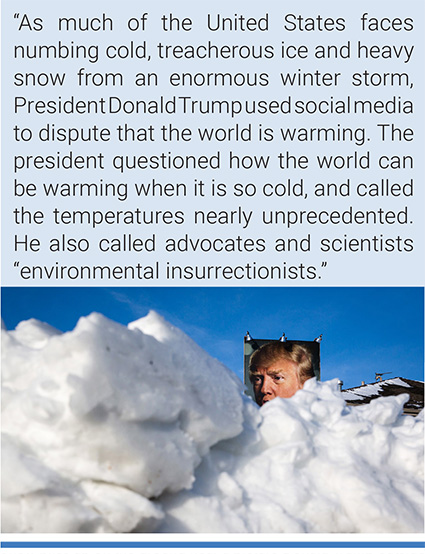

In North America, a cold snap on the US East Coast prompted President Trump to comment from the bully pulpit and inevitably news outlets covered his emissions. For example, Associated Press journalist Seth Borenstein noted, “As much of the United States faces numbing cold, treacherous ice and heavy snow from an enormous winter storm, President Donald Trump used social media to dispute that the world is warming. In a 25-word post on his Truth Social account, the president Friday questioned how the world can be warming when it is so cold, and called the temperatures nearly unprecedented. He also called advocates and scientists “environmental insurrectionists.” More than a dozen scientists Friday told The Associated Press the president’s claims were wrong. They point out that even in a warmer world, winter and cold occur, and they never said otherwise. They note that even as it is cold in the eastern United States, more of the world is warmer than average. They also stressed the difference between daily and local weather and long-term, planetwide climate change. Meteorologists also said that global warming over the past couple of decades may make this cold seem unprecedented and record-smashing. But government records show it has been much colder in the past”.

Next, several January 2026 stories drew on primarily scientific themes when reporting on climate change or global warming. For instance, the peak warming observed between 2023 and 2025 is considered by scientists as further evidence of the accelerating pace of global warming. La Vanguardia journalist Antonio Cerrillo wrote “2025 was the third warmest year on record, according to data from the Copernicus program: it was only slightly cooler (0.01°C) than 2023 and 0.13°C cooler than 2024, the warmest year on record. The last 11 years have been the 11 warmest ever recorded. As a result, temperatures over the last three years (2023-2025) have exceeded, on average, the pre-industrial level (1850-1900) by more than 1.5°C. (…) “This is significant because it indicates that we are approaching the threshold set in the Paris Agreement, something that could be reached in this decade of the 2020s,” Carlo Buontempo, director of the Copernicus Climate Change Service, told La Vanguardia.”. Elsewhere, Associated Press journalist Seth Borenstein reported, “Earth’s average temperature last year hovered among one of the three hottest on record, while the past three years indicate that warming could be speeding up, international climate monitoring teams reported. Six science teams calculated that 2025 was behind 2024 and 2023, while two other groups — NASA and a joint American and British team — said 2025 was slightly warmer than 2023. World Meteorological Organization, NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration officials said 2023 and 2025 temperatures were so close — .02 degrees Celsius (.04 degrees Fahrenheit) apart — that it’s pretty much a tie. Last year’s average global temperature was 15.08 degrees Celsius (59.14 degrees Fahrenheit), which is 1.44 degrees Celsius (2.59 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than pre-industrial time, the World Meteorological Organization calculated, averaging out the eight data sets. The temperature data used by most of the teams goes back to 1850. All of the last three years flirted close to the internationally agreed-upon limit of 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) of warming since the mid-19th century. That goal for limiting temperature increases, established in Paris in 2015, is likely to be breached by the end of this decade, the scientists said”.

The extra heat makes hurricanes and typhoons more intense, causes heavier downpours of rain and greater flooding, and results in longer marine heatwaves. Photograph: Michael Probst/AP. |

Meanwhile, Guardian environment editor Damien Carrington reported on a new peer-reviewed journal article in the journal Advances in Atmospheric Sciences, noting, “The world’s oceans absorbed colossal amounts of heat in 2025, setting yet another new record and fueling more extreme weather, scientists have reported. More than 90% of the heat trapped by humanity’s carbon pollution is taken up by the oceans. This makes ocean heat one of the starkest indicators of the relentless march of the climate crisis, which will only end when emissions fall to zero. Almost every year since the start of the millennium has set a new ocean heat record. This extra heat makes the hurricanes and typhoons hitting coastal communities more intense, causes heavier downpours of rain and greater flooding, and results in longer marine heatwaves, which decimate life in the seas. The rising heat is also a major driver of sea level rise via the thermal expansion of seawater, threatening billions of people. Reliable ocean temperature measurements stretch back to the mid-20th century, but it is likely the oceans are at their hottest for at least 1,000 years and heating faster than at any time in the past 2,000 years. The atmosphere is a smaller store of heat and more affected by natural climate variations such as the El Niño-La Niña cycle. The average surface air temperature in 2025 is expected to approximately tie with 2023 as the second-hottest year since records began in 1850, with 2024 being the hottest. Last year the planet moved into the cooler La Niña phase of the Pacific Ocean cycle”.

Figure 4. Examples of newspaper front pages with climate change stories in January 2026.

A man buys fish at a market in Tokyo. Across Japan, businesses and enterprising individuals in the fisheries industry are trying to make the best of the changes brought about by climate change. Photo: Reuters. |

Last, cultural-themed stories relating to climate change or global warming also were evident in January, showing that climate change is not a single issue but a set of intersecting issues that thread through our lives and livelihoods, weaving through the many ways we work, play, recreate, play and rest in this world. To illustrate, there were media stories connecting Australian heatwaves and impacts on the annual Australian Open Grand Slam tennis tournament. For example, Associated Press correspondent Charlotte Graham-McClay wrote, “Parts of Australia sweltered in record temperatures of close to 50 degrees Celsius (122 degrees Fahrenheit) on Tuesday as the country sweated through a prolonged heat wave. The rural towns of Hopetoun and Walpeup in Victoria state registered preliminary highs of 48.9 C (120 F), which if confirmed overnight would top records set on the day in 2009 when 173 people were killed in the state’s devastating Black Saturday bushfires. No casualties were reported from Tuesday’s heat wave, but Victoria authorities urged caution as three forest fires burned out of control. Melbourne, the state’s largest city, also came close to its hottest day. Nowhere perhaps was the searing heat more evident than at Melbourne Park, where the usual crowds thronging outside the Australian Open tennis tournament dwindled to a ghost town as temperatures soared. Inside, organizers enacted extreme heat protocols, forcing closure of the retractable roofs over the main arenas and postponement of matches on the uncovered outer courts. During Tuesday’s quarterfinal between Aryna Sabalenka and Iva Jovic — the last match played under scorching sun — the players held ice packs to their heads and portable fans to their faces during breaks in play”.

As another example of climate change stories bridging into the cultural realm, Japan Times correspondent Eric Margolis wrote, “Amberjack are swimming up to Hokkaido. Salmon are heading to Sakhalin. And brightly colored crimson sea bream are migrating from the tropics to the waters of the Izu Peninsula. As the planet warms, fish native to Japanese waters are swimming from south to north in pursuit of their desired temperatures, wreaking change on the nation’s regional diets and culture in the process. The drastic rate of change is particularly evident in Japan, since its oceans are heating up at rates more than double the global average. That equates to an average temperature gain of 1.33 degrees Celsius for waters around Japan in the past 100 years. But this drastic shift is far from evenly distributed. From Hokkaido to the Izu Peninsula to western Japan, the climate crisis is having chaotic and varied effects on Japan’s bays, channels, inlets and oceans — changing menus, customs, and even livelihoods”.

- report prepared by Max Boykoff, Rogelio Fernández-Reyes, Lucy McAllister, Ami Nacu-Schmidt, Jeremiah Osborne-Gowey and Olivia Pearman