Monthly Summaries

Issue 107, November 2025 | "Moral failure and deadly negligence"

[DOI]

Cars and houses are submerged in floodwaters in Songkhla province, Southern Thailand, on November 26, 2025. Photo: Arnon Chonmahatrakool/AP.

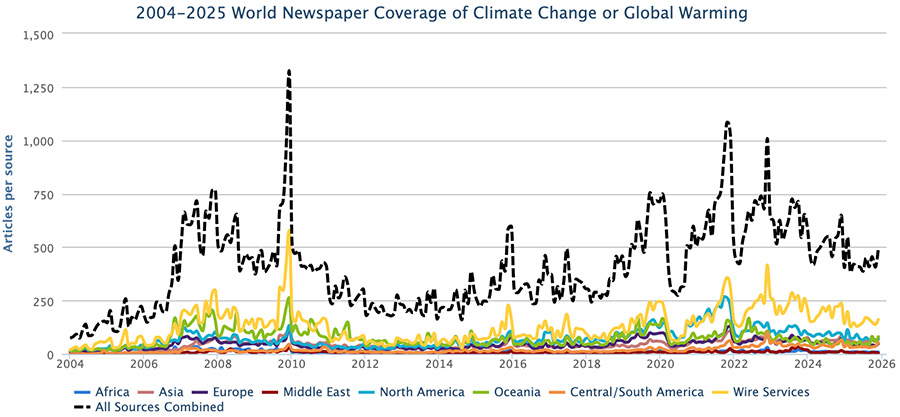

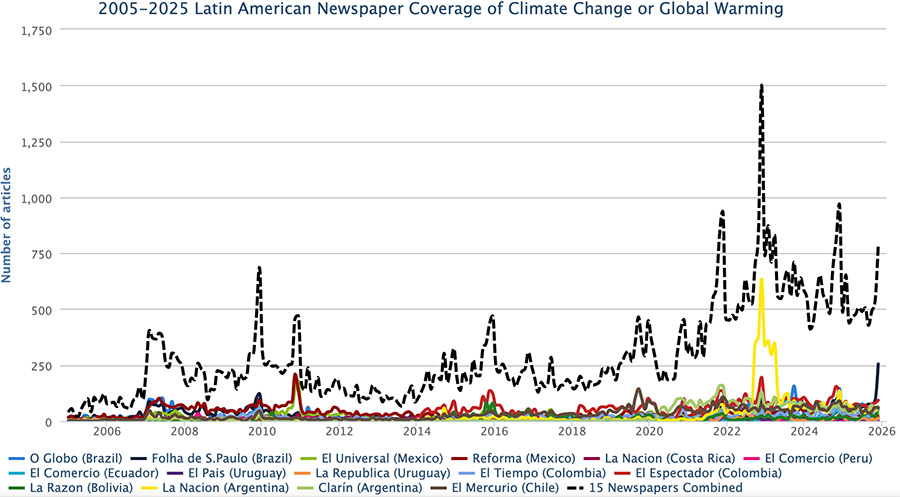

November media coverage of climate change or global warming in newspapers around the globe rose 23% from October 2025. Yet, coverage in November 2025 decreased 24% from November 2024 levels. Figure 1 shows trends in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – from January 2004 through November 2025. In particular, stories in Latin American outlets in November 2025 increased nearly 48% from October 2025 while the United Nations Conference of Parties meeting (COP30) on climate change took place in Belém, Brazil (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Newspaper media coverage of climate change or global warming in print sources in seven different regions around the world, from January 2004 through November 2025.

At the regional level, November 2025 coverage increased in most regions compared to October 2025, with exceptions in the Middle East (down 42%) and in Africa (down 9%): North America (+9%), Asia (+18%), the European Union (EU) (+25%), Oceania (+43%) and aforementioned Latin America (+48%) compared to October 2025. As an example at the country level (where we provide 15 country profiles around the world in 14 different languages overall), coverage in United Kingdom (UK) print newspapers – The Daily Mail & Mail on Sunday; Guardian & Observer; Sun, The News of the World & Sunday Sun; Telegraph & Sunday Telegraph; The Daily Mirror & Sunday Mirror; and Times & Sunday Times – increased 28% from the previous month of October 2025 yet was still 34% lower than coverage in November 2024.

Figure 2. Latin America print media coverage of climate change or global warming from January 2005 through November 2025.

Turning to the content of news coverage in November 2025, news reporting included many political and economic-themed media stories about climate change or global warming. The annual UN climate change negotiations (COP30) dominated news stories in the first weeks of the month, with many angles on facets of the negotiations and related activities. For example, Guardian journalists Jonathan Watts and Fiona Harvey reported, “The failure to limit global heating to 1.5C is a “moral failure and deadly negligence”, the UN secretary general has said at the opening session of the Cop30 climate summit in the Brazilian city of Belém. António Guterres said even a temporary overshoot would have “dramatic consequences. It could push ecosystems past catastrophic tipping points, expose billions to unlivable conditions and amplify threats to peace and security.” Speaking to heads of state from more than 30 countries, Guterres called the target of limiting global heating to 1.5C above preindustrial levels a “red line” for a habitable planet and urged his audience to bring about a “paradigm shift” so that the effects of the overshoot could be minimized”.

A delegate from the Russian Federation raised the country’s nameplate to interrupt the session and protest the conduct of Latin American countries during negotiations. Photo: Alessandro Falco/The New York Times. |

At the end of the two-week COP30, there were many stories covering the progress made. For example, New York Times journalists Max Bearak and Lisa Friedman reported, “Global climate negotiations ended on Saturday in Brazil with a watered-down resolution that made no direct mention of fossil fuels, the main driver of global warming. The final statement, roundly criticized by diplomats as insufficient, was a victory for oil producers like Saudi Arabia and Russia. It included plenty of warnings about the cost of inaction but few provisions for how the world might address dangerously rising global temperatures head-on. Without a rapid transition away from oil, gas and coal, scientists warn, the planet faces increasing devastation from deadly heat waves, droughts, floods and wildfires. A marathon series of frenetic Friday night meetings ultimately salvaged the talks in Belém, on the edge of the Amazon rainforest, from total collapse. Oil-producing countries like Saudi Arabia were adamant that their key export not be singled out. They were joined by many African and Asian countries that argued, as they have in earlier talks, that Western countries bear unique responsibility in paying for climate change because they are historically responsible for the most greenhouse gas emissions. Around 80 countries, or a little under half of those present, demanded a concrete plan to move away from fossil fuels. Outside of Europe, they did not include any of the world’s major economies. After the gavel fell, André Corrêa do Lago, the Brazilian diplomat leading the talks, announced that his country would lead an independent effort to rally nations to develop specific plans for transitioning away from fossil fuels and for protecting tropical forests. The political effort would have no force of international law, but there was a round of polite applause from delegates.” As a second example, La Vanguardia published an editorial “Limited Progress Against Climate Change,” which stated, “while there were no major steps forward at the Belém climate conference, as the EU itself acknowledges, there were no steps backward. This is important because, despite current geopolitical tensions, collective progress in the right direction—multilateralism and solidarity—is being maintained. However, the conclusions of this COP30 lack the necessary force to increase pressure on governments and fall far short of what scientists consider necessary to achieve a truly stable and safe climate. Intensive, collective, and coordinated work will be needed on a global scale to achieve better results at COP31, to be held next year in Türkiye, where Australia will chair the negotiations.”

Following COP30 in Belém, the G20 summit was held in Johannesburg and there was coverage of climate change from that meeting as well. For example, La Vanguardia journalist Joaquín Vera wrote, “The host country's government warned, before the meeting began, that Donald Trump's boycott, which left the US chair vacant for the first time, would not cloud the proceedings: “The sun will continue to rise in the east and set in the west…the (almost) white smoke was announced: a minimal declaration addressing global challenges that strongly resent the US president, such as the importance of multilateralism and the severity of climate change. “Faced with this challenging political and socioeconomic environment, we reaffirm our commitment to multilateral cooperation to collectively address shared challenges,” the declaration reads, adding that “we recognize the urgency and severity of climate change.”

Figure 3. Examples of newspaper front pages with COP30 climate change stories in November 2025.

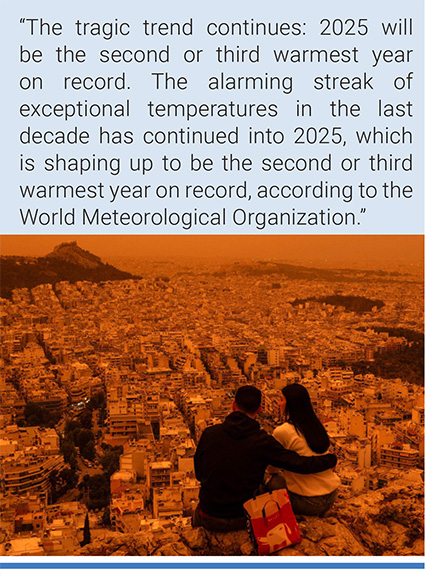

A couple sits on Tourkovounia hill as southerly winds sweep in waves of Saharan dust, in Athens. Photo: Angelos Tzortziis/AFP. |

Meanwhile, many November 2025 media stories featured several scientific themes in news accounts. The timing of the publication of several scientific reports and findings threaded into political and economic dimensions of COP30 negotiations as well. For example, in coverage relating to a UN Emissions Gap report released in early November New York Times correspondent Brad Plumer noted, “Countries have made very slight headway in the fight against global warming over the past year by tightening their policies to limit emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, according to a United Nations report released Tuesday. But there’s a catch: Some of that modest progress in tackling climate change could end up being canceled in the years ahead as the United States dismantles its pollution controls and other climate policies under President Trump, the report said. The U.N.’s annual Emissions Gap Report measures the disparity between what world leaders have promised to do to limit the rise in global temperatures and what they are actually doing to rein in carbon dioxide and other planet-warming gases from fossil fuels and deforestation. It typically finds that this gap is very large. This year’s report is no exception: Based on policies that countries have put in place and current technology trends, Earth is expected to warm by roughly 2.8 degrees Celsius (5 degrees Fahrenheit) this century, compared with preindustrial levels. If countries followed through on all of their official promises to cut near-term emissions, warming could be limited to 2.3 degrees Celsius, though many nations are struggling to meet those pledges. Those temperature levels are considerably hotter than what nearly every country agreed to under the 2015 Paris climate agreement, in which leaders promised to hold global warming to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius, and preferably closer to 1.5 degrees, to reduce the risks from wildfires, droughts and other climate calamities. Even half a degree of additional warming could mean tens of millions more people worldwide exposed to dangerous heat waves, water shortages and coastal flooding, scientists have said. (The world has already warmed about 1.3 degrees since preindustrial times).”

As a second example, La Vanguardia journalists Juan Manuel Campos and Antonio Cerrillo wrote about a World Meteorological Organizations report and noted, “The tragic trend continues: 2025 will be the second or third warmest year on record. The alarming streak of exceptional temperatures in the last decade has continued into 2025, which is shaping up to be the second or third warmest year on record, according to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). With this data, a tragic trend is confirmed: the last 11 years, from 2015 to 2025, will have been (each individually) the eleven warmest years in the 176 years of recorded observations, and the last three years have been the three warmest years ever recorded”.

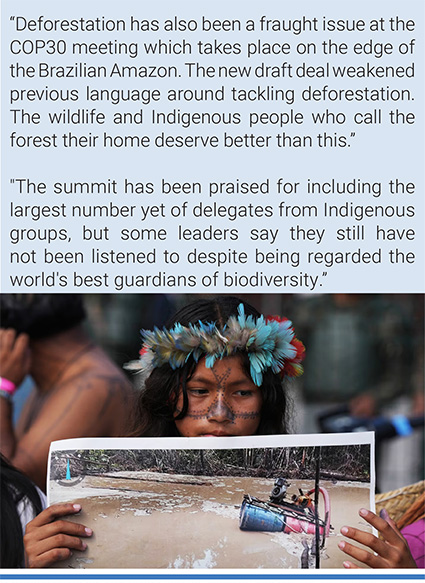

A woman advocates for protecting the Amazon, outside the UB Climate Summit in Belém, Brazil. Photo: Fernando Llano/AP. |

Similar to links between political and scientific stories in November, several media portrayals focused on cultural-themed stories relating to climate change or global warming and a subset of them focused on activities at and around COP30. For instance, BBC News correspondent Georgina Rannard reported, “A bitter row over fossil fuels has broken out at the COP30 UN climate talks in Belém, Brazil, as the meeting formally runs over time. At the heart of the row is a disagreement over how strong a deal should be on working to reduce the world's use of fossil fuels, whose emissions are by far the largest contributor to climate change. The dispute pits groups of countries against each other, but all 194 parties must agree in order to pass a deal at the two-week summit… Deforestation has also been a fraught issue at the meeting which takes place on the edge of the Brazilian Amazon. The new draft deal weakened previous language around tackling deforestation. "The wildlife and Indigenous people who call the forest their home deserve better than this," said Kelly Dent, Director of External Engagement for World Animal Protection. The two-week meeting has been interrupted by two evacuations. Last week a group of protesters broke in carrying signs reading "Our forests are not for sale". On Thursday, a fire broke out, burning a hole through the sheeting covering the venue and causing 13 smoke inhalation injuries. The summit was evacuated and closed for at least six hours. The summit has been praised for including the largest number yet of delegates from Indigenous groups, but some leaders say they still have not been listened to despite being regarded the world's best guardians of biodiversity.” As a second example, Washington Post journalists Jake Spring and Marina Dias wrote, “Brazil intended this year’s United Nations climate talks now underway in the Amazon rainforest, to be the capstone of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s effort to establish the country as a global environmental leader… Even Brazil, where Lula is extremely vocal about climate change, is struggling with putting environment as its top priority as it pushes ahead with oil drilling and takes steps to weaken conservation. Brazil has heaped high expectations on itself. Lula narrowly won election in 2022 over President Jair Bolsonaro, who dismantled Brazil’s environmental protections and threatened to leave the Paris agreement climate treaty. Left-wing Lula was hailed as an environmental savior at that year’s climate talks, with crowds following him around the venue in Egypt chanting his name, as he pushed for Brazil to host COP30 even before taking office. He also vowed to end deforestation in the country by 2030 and created the first Ministry of Indigenous Peoples”.

Figure 4. Examples of newspaper front pages with climate change stories in November 2025.

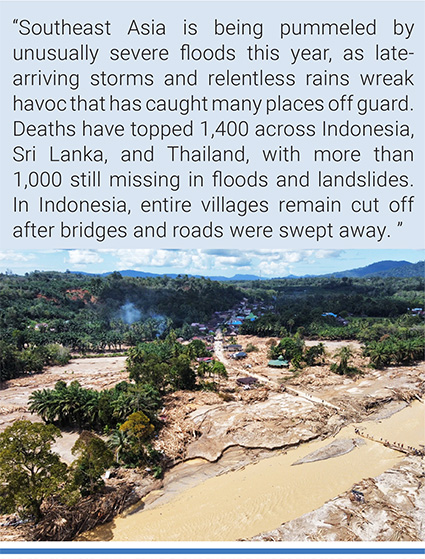

This aerial photo taken using drone shows a village affected y a flash flood in Batang Toru. North Sumatra, Indonesia. Photo: Binsar Bakkara/AP. |

Yet, COP30 did not use up all the ink for climate change coverage in November. As an example of cultural stories not linked to COP30, CBC News reporter Brett Forester reported, the “assembly of First Nations chiefs voted unanimously on Tuesday to demand the withdrawal of a new pipeline deal between Canada and Alberta, while expressing full support for First Nations on the British Columbia coast that strongly oppose the initiative. Hundreds of First Nations leaders are gathered this week in Ottawa for their annual December meeting, where high on the agenda was the federal-provincial memorandum of understanding for a bitumen pipeline to Asian markets announced last week. The deal contemplates changing the federal ban on oil tanker traffic in northern B.C. waters, but AFN delegates responded by passing an emergency resolution affirming their support for the moratorium. "A pipeline to B.C.’s coast is nothing but a pipe dream," said Chief Donald Edgars of Old Massett Village Council in Haida Gwaii, who moved the resolution. The resolution also urges Canada, Alberta and B.C. to recognize the climate emergency and uphold the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.”

Last, there continued be many media stories relating to ecological and meteorological dimensions of climate change or global warming in November. To illustrate, early in the month the devastation wrought by Typhoons Fung-wong and Kalmaegi – with links made to a changing climate – generated media attention. For example, in early November CBS News reported, “Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. declared a state of emergency due to the extensive devastation caused by Kalmaegi and the expected damage from Fung-wong, which was also called Uwan in the Philippines…the Philippines is hit by about 20 typhoons and storms each year, but scientists have warned repeatedly that tropical storms are getting more powerful and less predictable due to human-driven climate change. Warmer seas enable typhoons to build into bigger storms more rapidly, and a warmer atmosphere holds more moisture, meaning tropical storm systems bring heavier rainfall.” As a second example, BBC News reporters Kathryn Armstrong, André Rhoden-Paul and Lulu Luo wrote, “The Philippines - located near the area where Pacific Ocean tropical weather systems form - is one of the most vulnerable countries in the world to cyclones. About 20 tropical cyclones form in that region every year, half of which affect the country directly. Climate change is not thought to increase the number of hurricanes, typhoons and cyclones worldwide. However, warmer oceans coupled with a warmer atmosphere - fueled by climate change - have the potential to make those that do form even more intense. That can potentially lead to higher wind speeds, heavier rainfall, and a greater risk of coastal flooding.” As another example, in later November Associated Press correspondents Aniruddha Ghosal and Anton L. Delgado wrote, “Southeast Asia is being pummeled by unusually severe floods this year, as late-arriving storms and relentless rains wreak havoc that has caught many places off guard. Deaths have topped 1,400 across Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand, with more than 1,000 still missing in floods and landslides. In Indonesia, entire villages remain cut off after bridges and roads were swept away. Thousands in Sri Lanka lack clean water, while Thailand’s prime minister acknowledged shortcomings in his government’s response. Malaysia is still reeling from one its worst floods, which killed three and displaced thousands. Meanwhile, Vietnam and the Philippines have faced a year of punishing storms and floods that have left hundreds dead. What feels unprecedented is exactly what climate scientists expect: A new normal of punishing storms, floods and devastation…Atmospheric levels of heat-trapping carbon dioxide jumped by the most on record in 2024. That “turbocharged” the climate, the United Nation’s World Meteorological Organization says, resulting in more extreme weather. Asia is bearing the brunt of such changes, warming nearly twice as fast as the global average. Scientists agree that the intensity and frequency of extreme weather events are increasing. Warmer ocean temperatures provide more energy for storms, making them stronger and wetter, while rising sea levels amplify storm surges, said Benjamin Horton, a professor of earth science at the City University of Hong Kong. Storms are arriving later in the year, one after another as climate change affects air and ocean currents, including systems like El Nino, which keeps ocean waters warmer for longer and extends the typhoon season. With more moisture in the air and changes in wind patterns, storms can form quickly.”

- report prepared by Max Boykoff, Rogelio Fernández-Reyes, Ami Nacu-Schmidt, Jeremiah Osborne-Gowey and Olivia Pearman